New Sleeper Disc Has Strong Music, Local Talent

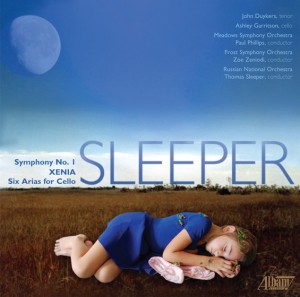

In a time when many composers have to spend as many days making sure they keep the publicity going as they do actually writing, Thomas Sleeper has enjoyed steady releases on established classical labels, including a Naxos disc of wind music and a just-released disc of orchestral pieces on Albany.

The new Sleeper collection includes the Symphony No. 1, a song cycle called Xenia that features tenor John Duykers, and a suite of pieces for solo cello and orchestra, with cellist Ashley Garritson. Like much of his work, this is serious, dramatic music, with a strong dark undercurrent beneath more or less traditional structures. No matter how stark and nominally harsh his harmonies can be, there’s a secure tonal center that helps make sense of his narrative line.

In that, he resembles many of the 20th-century composers who declined to leave tonality behind for the lure of the Second Viennese School, and on this disc, there are kinships with them, and Shostakovich in particular. The First Symphony, sensitively and compellingly played here by the Meadows Symphony Orchestra of Dallas’ Southern Methodist University, under conductor Paul Phillips, shares with the work of the Russian composer (and one of his greatest influences, Gustav Mahler) a slow movement that is the longest part of the work, and the one the maps the most elaborate emotional terrain.

This was true of Sleeper’s String Quartet No. 3 as well, which the longtime University of Miami faculty member wrote for the Delray String Quartet in what proved to be one of the 2008-09 season’s most notable premieres (one still hopes for a recording of the work by the group for whom it was written). The symphony’s other three movements, particularly the opening Andante mosso-Agitato, bustle with a sharp but not prickly energy, and its overall profile is one that should do well on innovative symphonic programs.

Xenia, sung here by Duykers, perhaps best-known for his role as Mao Zedong in John Adams’ Nixon in China (which I saw in Washington in 1987), is a selection of poems about the exile of the Roman poet Ovid, drawn from a book called The Love-Artist by the writer Jane Alison, a colleague of Sleeper’s at UM. These are lovely poems about artistic immortality in which Ovid looks to posterity while hoping to get the answer about his works’ survival from a young girl named Xenia, gifted with clairvoyant powers.

In the final song, it’s clear that Ovid will triumph, as Xenia hears his poems live on (I hear your words yes/From the deepest black sea). This cycle also reminded me of Shostakovich and of Britten, particularly in the Peter Grimes-like water music of the second song, and the back-and-forth waltz of the last song.

What’s evident here is Sleeper’s ability to paint an impressive dramatic picture from the text, and unify it in a cycle: These don’t sound like separate songs, separately considered; they work well with each other and build logically to the last climax. Duykers sings with the kind of heightened voice (Sleeper’s notes call it “Sprechstimme-like,” though it’s less angular than Schoenberg, for instance) that carries the drama of the cycle well, and UM’s Frost Symphony Orchestra acquits itself admirably under the direction of its assistant conductor, Zoe Zeniodi.

The disc closes with another cycle, Six Arias for Cello and Orchestra, recorded in Moscow with members of the Russian National Orchestra directed by Sleeper himself. This work is based on a previous song cycle Sleeper wrote in 1996, and each aria has titles such as Hora mortis nostrae (The hour of our death, a line from the Ave Maria), which adds to this music’s often-sober feel. Cellist Garritson brings high emotion and penetrating tone to the music, and while the ending (subtitled Chthonios) doesn’t quite come off with the kind of exuberance Sleeper seems to be aiming for, the middle arias in the work sing out beautifully.

The disc has a lot of strong local talent on it – Sleeper, Zeniodi, Alison, Garritson, the Frost Symphony – and that buttresses the argument for the impressive depth of the classical music community here. It’s a good outing by an increasingly established composer, and one hopes the larger classical world gives it a serious listen.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·