Clear writing at foundations: An issue we won’t give up on

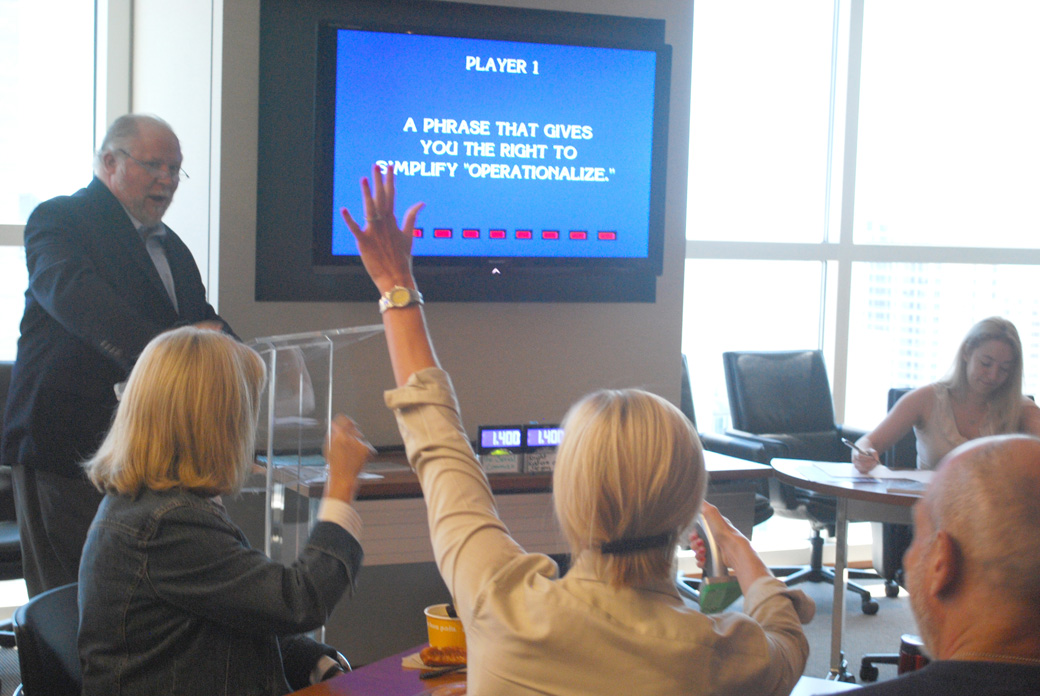

At Knight Foundation, we believe clear writing makes our work more effective. If you have ever seen a sentence promising that one of our grantees will “leverage the stakeholder infrastructure” you know exactly what I mean. If no one can understand us, if we can’t even understand ourselves, how are we going to help communities become more informed and engaged? On our website is a guide for press release writing, an explanation of the readability standard we use, the Flesch score, and, below, an opinion piece I wrote on the subject for the Chronicle of Philanthropy. Clear writing doesn’t have to be a chore. It can be fun: the picture in this blog is of me leading a “game show” seminar for the staff called Jargon Jeopardy.

For Foundations, Clearer Writing Means Wiser Grant Making

by Eric Newton

Clarity matters. That seems obvious. Yet in our nation’s capital, when the Sunlight Foundation this spring released a study measuring how well lawmakers communicate, we learned even clarity can be controversial.

Sunlight found that members of Congress have made a big leap these past seven years in their ability to talk clearly. You would think all would jump for joy. We want open government: Clear talk is more accessible than jargon. But no. Sunlight’s news release—and most of the news-media coverage—took a different tack. They asked: “Is Congress getting dumber or just more plainspoken?”

That’s just wrong, and it brings into focus a big issue for foundations.

Too often, we fall into the trap of believing complex communication equals intelligence. Fancy words mean you’re smart; simple words mean you’re dumb. Because my foundation, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, was founded by two of America’s leading newspapermen, we think about this topic a lot and we believe the opposite is true. You have to be smart to convey difficult subjects in clear, understandable prose. If you can do it, your work will be more effective.

To measure Congress, Sunlight used something called the Flesch score. Rudolf Flesch, author of Why Johnnie Can’t Read—and What You Can Do About It, created this measure of readability. The higher your Flesh score, the more understandable you are. The clearer you are, the more people you can reach. Let’s test the Flesch score of a classic children’s song:

Three blind mice Three blind mice See how they run See how they run They all ran after the farmer’s wife Who cut off their tails with a carving knife Have you ever see such a sight in your life As three blind mice?

Run a spell check in Microsoft Word, and if your settings are right, a Flesch score will pop up. Without line breaks, “Three Blind Mice” scores a nifty Flesch 70. No wonder everyone understands it.

Yet if foundations sang “Three Blind Mice,” it would go more like this:

Three rodents with defective visual perception Three rodents with defective visual perception Visualize how they perambulate Visualize how they perambulate They all perambulated after the agricultural spouse Who severed their appendages with a kitchen utensil Have you ever visualized such a spectacle in your existence As three rodents with defective visual perception?

That scores a Flesch 0 (on a scale of 0 to 100). Unlike Coke Zero, Flesch 0 is a bad thing. Too often, this is how we in philanthropy talk and write. We litter our prose with jargon. Our message becomes ambiguous. Truly, how can we expect to help people if they can’t understand us?

At the Knight Foundation, our mission is to advance “informed and engaged communities.” That just can’t happen without clarity. So we use the Flesch score. We try to keep our internal documents at a Flesch 30 or greater, our press releases Flesch 40, and our speeches Flesch 50. Since any readability test is only a rough measure, we don’t sweat decimal points. Numbers rounded off are fine.

Knight is certainly not the only foundation that believes you must be part of society to help improve it. Michael Bailin, when president of the Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, wrote: “The real threat of unclear language is its power to extinguish thoughtful public discourse.”

Indeed. How can we expect a community to act on a study if it can be understood only by a few Ph.D.’s?

Even worse, noted Tony Proscio, author of Bad Words for Good, is what folks do when they don’t understand: “People who can’t puzzle out your real meaning will soon draw their own inferences about it.” (Congratulations to Mr. Bailin for financing Mr. Proscio’s work on clear foundation writing.)

After 11 years of grant making, I’ve learned, sometimes the hard way, that clarity does matter. When our writing is clear, we understand each other. Foundation paperwork moves faster, questions are fewer and smarter, our discussions are richer, and the money we give away achieves more. People know what they are trying to do and why. Clear writing allows all parties to get on the same page and move in the same direction. Think about a grant as a common dream of a better future. Clear writing helps us dream together.

It can be fun. At Knight Foundation, we run seminars like “Writing Tips and Tricks.” We have a consulting writing coach, Mary Ann Hogan. Just the other day, we gathered at lunchtime to play “Jargon Jeopardy,” a version of the game show that rewarded clear thinking. My favorite team name was the “Serial Commas.”

My favorite game moment was when the word “stakeholder” came up. The host (me) joked that the only stakeholder who lived up to the title was Buffy the Vampire Slayer. She not only held stakes but plunged them into the hearts of the undead. I sometimes wish I could do that to the news releases that foundations put out.

Federal agencies have been urged to keep their writing simple. Under the new Plain Writing Act, officials must communicate more clearly with the public. Even the feds now must use the active voice, avoid double negatives, favor personal pronouns, and run the other way if someone says “incentivizing.”

The nonprofit Center for Plain Language, founded for federal workers, gives awards for the best and worst of government-speak, including a “turnaround” prize for the most improved agency. If lawmakers were given awards like that, maybe they would get even better.

The Sunlight Foundation knows it overcooked its news release. Flesch tests estimate the minimum grade level that can understand a piece of writing. But they have absolutely nothing to do with the intelligence of the speaker.

The average American communicates at about an 8th-grade level. That does not mean America is in the 8th grade. It only means that we prefer a level of clarity that can be understood by everyone all the way down to the 8th grade. Congress is now talking at a grade level that reaches down to the 10th grade; it used to be the 11th grade. So its members got a little clearer but not “dumber.”

If you ask me, they are still not clear enough. There’s still a lot of “Three Rodents With Defective Visual Perception” going on in Washington. (That version of the song, by the way, scores at Grade 28. It’s pretty easy to hide what you’re really doing if that’s the tune you’re singing.)

Of course, clarity doesn’t equal truth. But it helps. Though Sunlight was wrong to equate simple words with simplemindedness, it still did two good things.

First, it raised the issue. Second, it called attention to an amazing new Web site it created: capitolwords.org. The site is a gift of the digital age. You can type in a word and see who said it in Congress, when, and why. You can see what words were most used each day, track their usage over time, see which words your member of Congress used most. You can even type in “clarity” and see what kind of debate Sunlight created with its study.

The holy book of clear writers is The Elements of Style. Hear its wisdom: “Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.”

What is the penalty, in foundation work, for writing that does not make every word tell? We waste money that isn’t ours to waste.

I remember years ago looking at a report from a longtime grantee. The project was to get young people into a certain career. After a decade, and considerable expense, not one young person who had gone through the program had gotten into that profession. I looked carefully at the reports and at our grant documents. The grantee’s work fell within the language of the grant. But the grant never set a clear goal. Talk about “defective visual perception.”

If I could wave a magic wand: Grantees would help edit foundation paperwork about their projects. Grant write-ups (our internal summaries) would be so clear they could be news releases. Grantee reports would be so honest you could put them right online. Grantees would blog their benchmarks. The foundation would speak not only of what it has done, but candidly about what it’s thinking of doing and why.

How do you make these big changes? One word at a time. So, when you next look down at the sentence in that grant write-up that says, “The primary stakeholder will operationalize the leverage so they can scale their sustainability infrastructure,” please change it to “They will hire a fundraiser.”

Eric Newton is senior adviser at the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation in Miami. Amy Starlight Lawrence and Annahita Irani helped with the research for this article, which is a Flesch 67.