Bob Maynard, media diversity, and a story without an ending

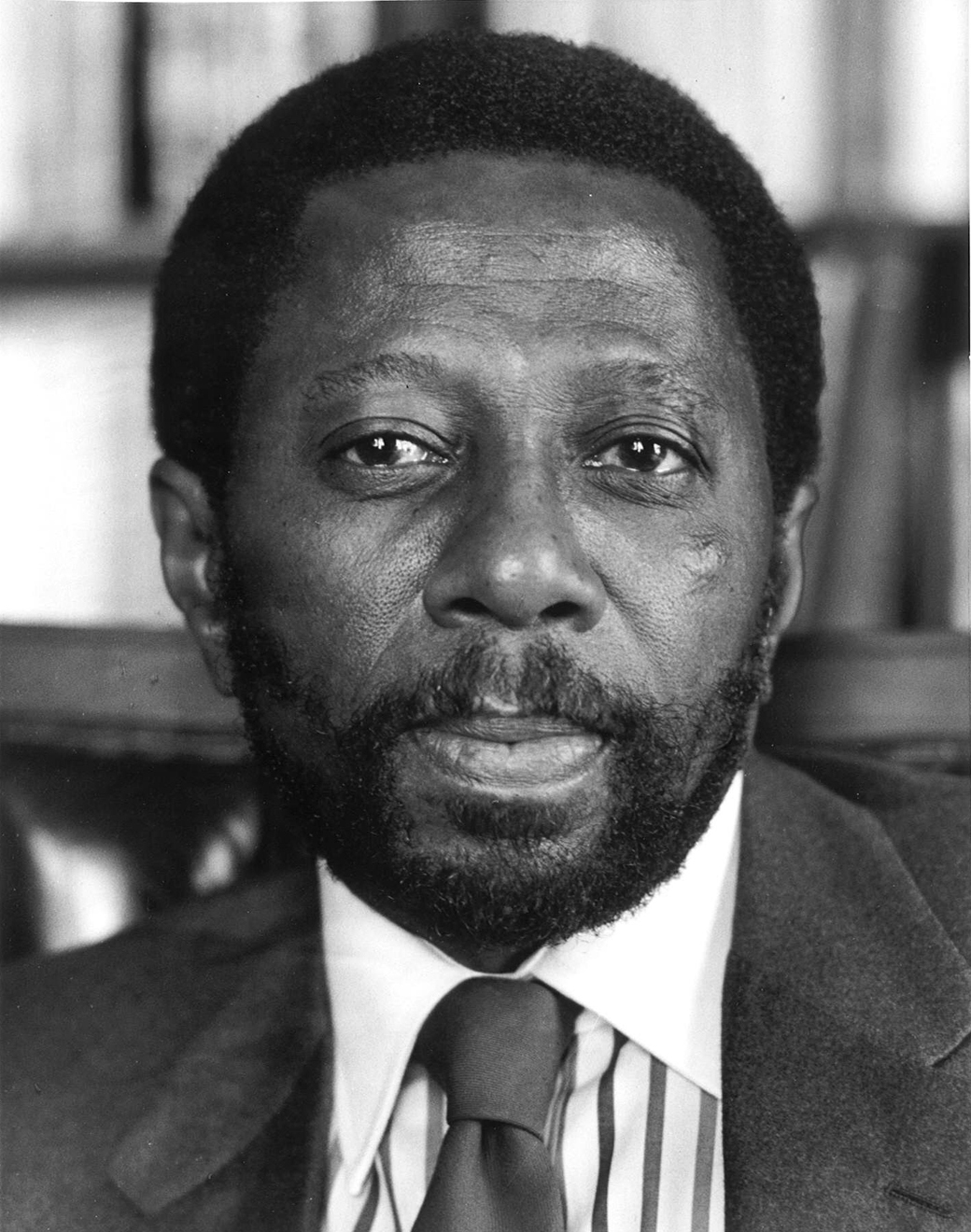

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the death of Robert C. Maynard, visionary journalist, champion of media diversity and my mentor at the Oakland Tribune. The piece below reflects what it felt like to work for Bob. I don’t remember much about reading it at his memorial service, only the tears. So I read it again every year. Bob’s “fault lines” ideas predicted the digital divide we see today between old and young, poor and rich, rural and urban. I think the best way to honor him this year is to support the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education, which is run by Bob’s daughter Dori Maynard and is dedicated to Bob’s goal of giving all Americans “front door access to the truth.” Photo credit: Angela Pancrazio/Oakland Tribune.

There are enough Bob Maynard stories to last forever – and we will tell them all.

In 1989, there was an earthquake. We were in the old, brick Tribune Tower downtown. The tower shook, but it didn’t fall. Plaster dust and silence filled the newsroom. Journalists, usually talkative, crawled out from under their desks and moved through the yellow air like an army of Zombies, making their way to the stairs. I raced through the newsroom, making sure everyone was out. I took one last look at the empty room. The phone rang. I reached out for it. A hand appeared on my shoulder, stopping me, and I heard that deep, warm, beautiful voice.

He said, “It’s time for YOU to get outside.”

That was Bob.

I would not be the last one out of the newsroom that day.

In 1991, also in October, there was a fire. Bob was the first journalist to call me about it. “Big fire on the hill,” he said. I made a call and told him the official sources said it was just a little grass fire. By this time, Bob had access to a scanner, binoculars and his camera – and he told me what he thought of the official reports. I live just five minutes from the office, but by the time I got there, the sky was dark, dark brown. Bob arrived a bit later – delayed because the family had to evacuate. The fire was burning at 2,000 degrees. It had destroyed 3,000 dwellings and killed people, and it was in his backyard. The family arrived at the office. I asked Bob to write a story for the front page. He did it in an hour. But it was a story about an ending – since he didn’t know that firefighters were miraculously saving his house.

When he walked into the news meeting that night, he only had one question: “What are we doing for the victims?”

That was Bob.

And the newspaper became like him – warm and deep and beautiful.

In 1993, a great man was in pain, dying of cancer. All he could think of were his friends, who had just had a baby, a baby that struggled the first few days of his life. The voice came on the telephone this time. “I wanted to be sure YOU were OK.”

That was Bob, as compassionate as he was brilliant. Soft – and sharp. An impossible combination that allowed him, and those he touched, to do the impossible.

Of all the big stories we’ve worked on together, Bob – this one is the biggest, and the worst. This is the first time I have lost someone I loved. I had a lot of firsts with you, Bob. But I don’t like this one.

You would give people chances. When we were afraid and we didn’t think we could, we could come to you, or call you, and after we talked to you we not only thought we could, we did.

On the surface, and by conventional wisdom, the two of us might not have had much to talk about. I was a white kid from the suburbs. Bob was my urban, African-American elder. But we could talk about anything. Bob made it that way. He was one of the greatest bridge builders the world has ever known.

Bob was big on endings. He would say that columns should be written with an ending that brings it all together, in an illuminating, and, if possible, surprising way.

But this needs to be a story without an ending.

Cancer – like fire and earthquakes – doesn’t know the difference between good people and bad. It just kills. It is up to us to separate out the good, to love it and keep it alive. Forever.

We will, Bob.

By Eric Newton, senior adviser to the president at Knight Foundation

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·