MUSAIC, a musical meeting house for the world

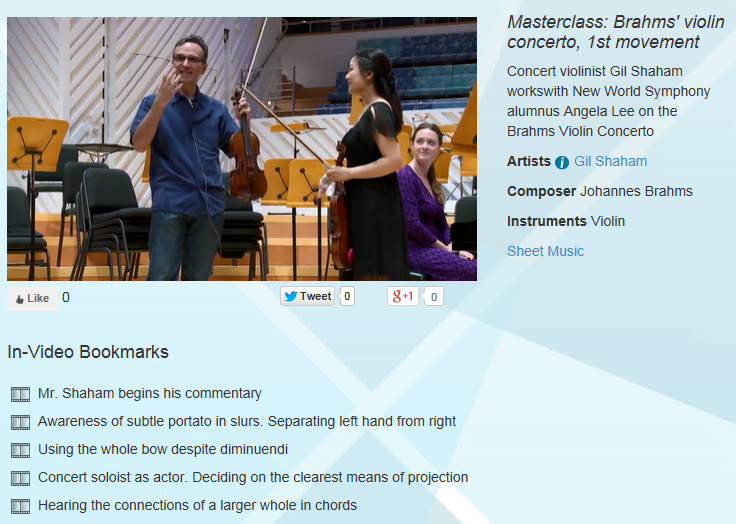

Gil Shaham leads a master class of Brahms’ violin concerto, 1st movement.

It’s a place where, a few keystrokes away, you can find cellist Yo-Yo Ma offering insights about the structure and interpretation of Bach’s “Suite No. 5 in C minor” for unaccompanied cello; have a former principal flutist at the Boston Symphony Orchestra give you some pointers on practicing scales; or just simply listen to a performance of Steve Reich’s modern classic “Music for 18 Musicians.”

In fact, the recently launched MUSAIC, an online community of classical musicians and video library curated by the New World Symphony, is that, and more, including master classes, conferences, live virtual hangouts and webcasts of events.

Co-founding artistic director of the New World Symphony “Michael [Tilson Thomas] used to talk about creating a global musical meeting house,” says Howard Herring, president and CEO of New World, while discussing the origins of the project. “We know about meeting houses. [It’s a place where] there are a lot of collisions, a lot of conversations, a lot of ‘Hey, do you know that piece? Do you have trouble where I have trouble? Let’s figure it out.’ Michael’s vision was ‘What if you can do this at a global scale?’ and in fact the digital world allows you to do it. So we started to experiment. “

MUSAIC is the culmination of a process that began in 2002, with a $200,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts that allowed New World to join Internet2, an international community comprising research institutions and academia, corporations and government agencies collaborating while using cutting-edge technologies. Then in 2008, New World received $5 million from Knight Foundation to create the Knight Media Endowment.

“It all tracks back to that [Knight] trusted us,” says Herring. The grants gave New World the freedom to explore “the capture, post-production and distribution of artistic and educational content across digital networks.”

New World Symphony set out to further its work in Internet 2, acquiring equipment for the capture and documentation of educational work, producing and presenting its free, outdoors WALLCAST concerts and commissioning video artists, animators and filmmakers to produce visuals to accompany classical music performances. A 2009 grant from the Kovner Foundation supported the development of an archival system and software platform for the delivery of teaching events. The sum result of all this is MUSAIC.

The site is a collaborative project that includes Cleveland Institute of Music, Curtis Institute of Music, Eastman School of Music (University of Rochester), Guildhall School of Music and Drama (London), Manhattan School of Music, Royal Danish Academy of Music, San Francisco Conservatory of Music, University of Missouri-Kansas City, and University of Southern California.

It was just launched on Sept. 23, 2014, but by mid-December, with little fanfare, MUSAIC had reached 28,681 unique users who conducted 44,387 sessions, logged 112,342 page views and registered 1,756 users.

“We keep the barrier low. We ask just for some basic information,” says Herring. “But we need these people if we are going to create this global musical meeting house.”

There is a wide-reaching, visionary quality to MUSAIC — but it’s a project undergirded by practical concerns. It is something addressed in many ways and many places throughout the site. It’s the core purpose of areas such as “Orchestral Excerpts” and “Audition Preparation,” but it’s also the idea behind “Reflections,” in which a professional player or composer may address anything from bowing technique to issues such as “Form in Composition.”

“The [fellows] are taking auditions throughout their time here and we build our curriculum to their aspirations,” says Herring. “The business of excerpts is critical because that’s how you get into orchestras.” But the practical view is something that also informs areas such as the open, unscripted, virtual hangouts, hosted by New World fellows. Besides, “it’s bedrock that our fellows understand the digital future,” adds Herring.

“What have been really helpful to me are the videos about audition preparation strategies,” says cellist Meredith McCook, a four-year fellow who is “taking a bunch of orchestra auditions right now.” She points out a series of videos featuring performance psychologist Noa Kageyama, noting that they “have been very helpful, especially some that are very specific in the countdown to an audition about things such as what you should be doing every day and how to organize your time.”

But McCook, who is featured in Yo-Yo Ma’s Bach video, also appears on the site as host of a couple of archived MUSAIC hangouts. “It’s very cool. It’s a work in progress right now,” she says. She especially likes the Side by Side videos in which “we try to reach out to high school students because we were high school students once upon a time; we know what they are going through and we want to encourage them and give them some advice.”

As Tilson Thomas states in his welcome video, “the kind of information contained in MUSAIC is what teachers have traditionally passed on to their students. Now we are hoping in this form, to make it more available to all of you.”

Herring notes that, for example, MUSAIC is gathering “an extraordinarily rich library.”

“Take the case of living composers. All living composers who come to New World—and there have been as many as 25 in a season—they talk about their music, they rehearse their music and they play their music. So we have this vertical representation, from nitty-gritty work to the final product with their comments all along,” says Herring.

“Ten, 15, 20 years down the line we are talking about 200 to 300 composers. One hundred years from now, somebody will look back and say, ‘What did John Adams think about for his saxophone concerto?’ Or will look at a marking [on the score] and say, ‘What did he mean by this?’ just like we look back now and think ‘Why did Beethoven put that metronome marking there?’ and try to glean his thinking — except that in the digital [realm] you can actually hear them say, ‘I want to hear it like this.’ How valuable is that? We are going to have this extraordinary, sophisticated and close look at what was in the composers’ imagination.”

The depth and variety of the library also enhances the potential of MUSAIC to appeal to the music community at large and to help develop audiences. Already, New World has used email campaigns, Facebook advertising, Twitter and other channels to expand MUSAIC’s reach. They also are paying attention to ways of improving the experience for mobile users. “Half of the users are on laptops; half are on iPads,” notes Herring.

“When I look at the audience for all of this online teaching it’s high school kids, college kids, some of whom are music majors others who just love music and still play even though they are science majors or English majors; it’s young professionals, it’s teachers, but also way out there, and this is still to be developed, it’s the audience for classical music.’

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·