The Clay Studio revisits history of Philadelphia ceramics by way of four seminal artists

Right now, a visit to The Clay Studio is a journey some 65 years back into the history of ceramics in Philadelphia. At this Knight Arts grantee, the exhibition “Fellowship in Clay: Philadelphia’s American Craft Council Fellows” looks at four influential ceramic artists who created one of the most successful university ceramics programs in the region. Showcasing work by William Daley, the late Rudolf Staffel, Paula Winokur and Robert Winokur (who are spouses), The Clay Studio focuses on two generations of mid- to late-20th-century clay artists that glazed the way for contemporary practices.

William Daley, “Totemic Figure.”

Some of Daley’s works look as much like something out of a natural history museum as objects created in a ceramic studio. Three pieces created in 1964 rest on pedestals, their rust-colored forms and gritty textures contrasting starkly with the white boxes that hold them. Each of them appears partly mechanical (which explains their oxidized exteriors), but also quite organic. With names like “Totemic Figure,” “Mantis Head” and “Torso,” the structures are clearly modeled after shapes in nature and human sculptural representations, although it looks as though they have been dug up after some centuries underground.

Staffel created delicate vessels that seem to change as the light shines on and through them. Pieces that rely on unglazed porcelain and occasional splashes of pastel colors have drawn comparisons between his work and that of a watercolor painter. Having been credited with inspiring the wider use of porcelain among ceramic artists, Staffel was also one of the original professors at Temple University’s Tyler School of Art, and was a teacher to both Paula and Robert Winokur during his time there.

Paula Winokur, “Above and Below I.”

Paula Winokur took Staffel’s porcelain-heavy approach to heart, and now constructs glacial forms and icebergs that call to mind the planet’s changing climate. “Above and Below I,” for instance, depicts a tall, cleaved form floating in a lucite ledge that mimics the icy ocean. Like an actual iceberg, this chunk of white material is more suspended below than above the surface, although Winokur’s view allows us to see the entire form in cross section. Elsewhere, “Glacial Mills” is a nine-panel, wall-mounted spread of icy terrain that looks like an aerial view instead of a submerged one, and “Iceberg/Split” looks as much like a sloppily iced cake as a broken chunk of floating glacier. Paula Winokur proves the versatility of porcelain with her work, and the results are as thought-provoking as they are pristine.

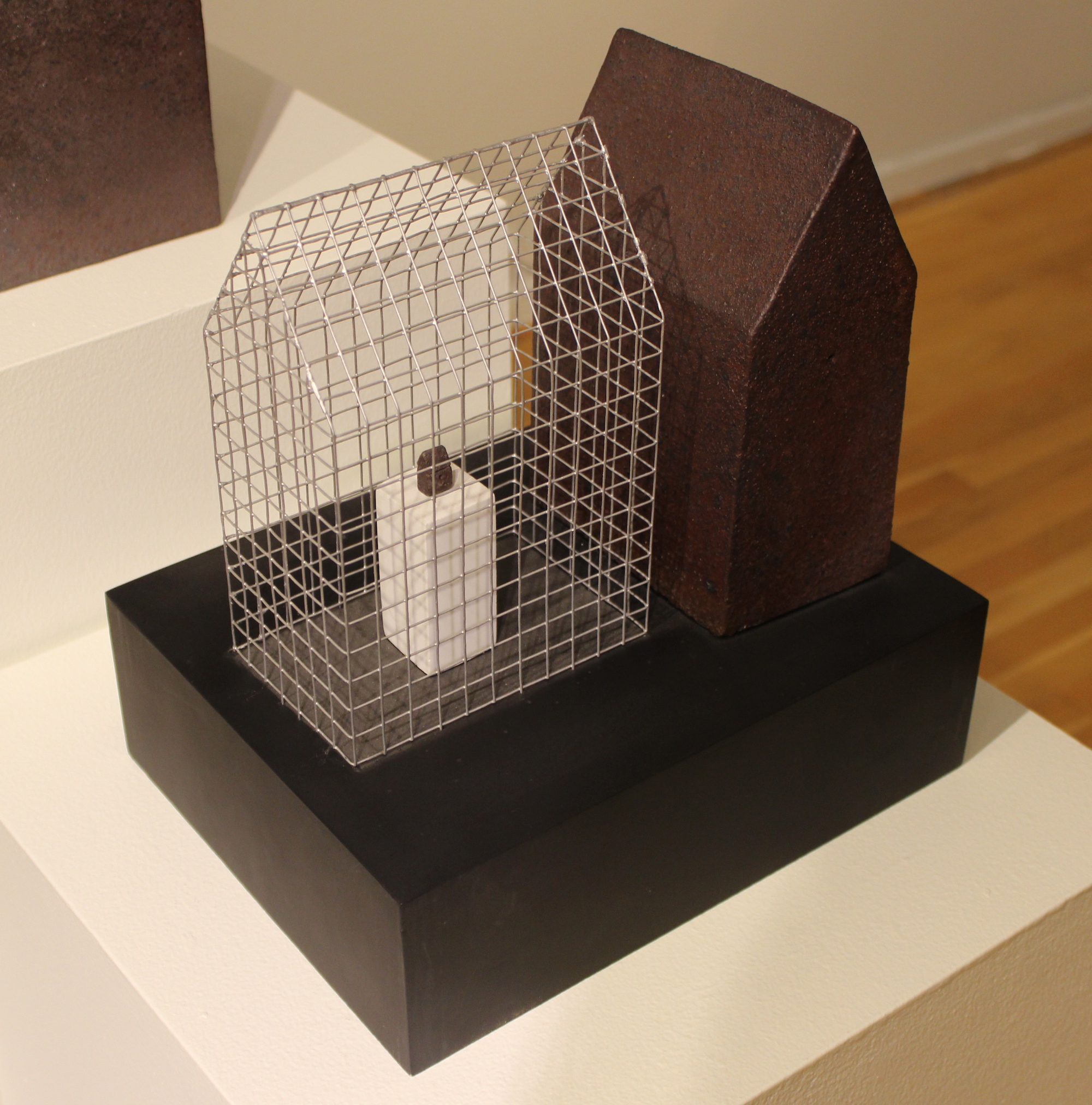

Robert Winokur, “Prodigy on Display.”

For his part, Robert Winokur seems to find his inspiration in the domestic. Many of his creations include tiny houses or other buildings, and in one series, many of these places contain, or are contained in, cages. One piece, “Prodigy on Display,” finds a dark brown house beside a metal cage. Inside the cage sits a white pedestal, with a very small, remarkably similar house on the pedestal. As an examination of domestic, nuclear-family lifestyles and White Cube gallery culture all at once, this piece is deceptively modest and also manages to challenge some of our more deeply held beliefs. When Robert Winokur isn’t trying to cause a stir, however, his wit can add a palpable sense of humor. In pieces like “Pear Pressure,” in which a square of yellow, ceramic pears is squeezed between two weighty blocks of clay, he creates a bizarre visual gag emphasized by the wordplay in the title.

All four of the individuals represented in this show have done much to further the creation of ceramics and education of clay artists in Philadelphia, and this is a rare opportunity to see work from each of them all in one place. Be sure to visit The Clay Studio before the show ends on Nov. 29.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·