Cooking change — one dish at a time

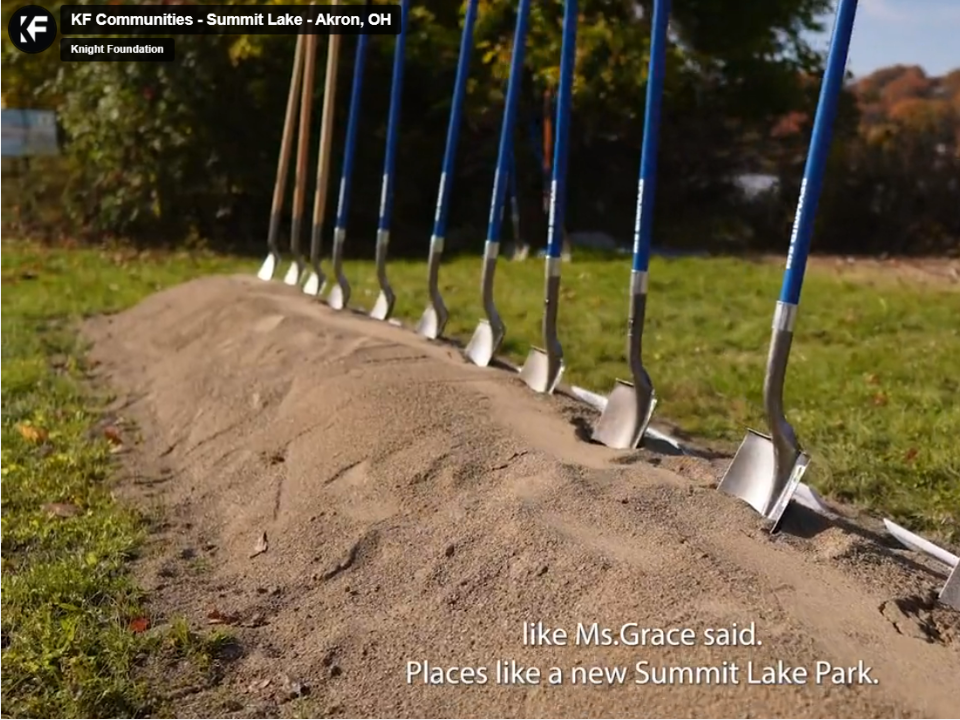

At Miami Culinary Institute, Aug. 14 lunch (picadillo with rice and beans and meatloaf with mashed potatoes) l to r: Tomas Bilbao, Cuba Study Group; Luis Alberto Alfonso Pérez, Michael Alejandro Calvo Oviedo, Gilberto Smith Álvarez and Yamilet Magariño Andux. Photo by Fernando González.

Four Cuban chefs and their South Florida hosts intently watched big screens at Miami Dade College’s Miami Culinary Institute last Friday as the American flag rose over the United States embassy in Havana. The import of the symbolic moment was inescapable.

The once improbable event also served as an exclamation point for the five-day visit of chefs Yamilet Magariño Andux, Gilberto Smith Álvarez, Luis Alberto Alfonso Pérez and Michael Alejandro Calvo Oviedo, the participants in the third installment of the Entrepreneurial Exchange Program. Funded in part by Knight Foundation, the program has been designed and managed by the Cuba Study Group, a non-partisan nonprofit based in Washington, D.C.

It was the first time that only chefs were part of the program. The first exchange took place almost a year to the day, and featured four women entrepreneurs in businesses as disparate as making soap, providing spa services, planning events and running a restaurant. The second exchange took place in May and it involved four Cuban entrepreneurs, also from various fields, including , food, clothing and printing and manufacturing of containers.

During the week, the Cuban chefs worked side by side and discussed business practices with their peers at places such as Wynwood Kitchen and Bar, Crumb on Parchment, Bread + Butter, Sushi Maki, Area 31, Bodega and Golden Fig. On Friday, the visitors participated in a lunchtime demonstration at the Miami Culinary Institute, cooking typical Cuban and American dishes alongside instructors and students. That same evening they offered short presentations at a fundraising event at Tuyo, the institute’s top-floor restaurant with its striking view of Freedom Tower—once a government processing center for refugees fleeing post-revolution Cuba.

Dramatic events provide the significant markers, but history is made of small changes, in the day-to-day. Call this the “Rice and Beans with Meatloaf” diplomacy.

The experience “really surprised me,” said Calvo, chef of the restaurant Atelier, one of the top restaurants in Havana. He cooked for New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and his delegation when they visited in April. On this exchange, Calvo visited different restaurants each day “and everywhere I was treated as if I was from here. For a chef, to allow a stranger in his kitchen is unusual. But here they opened their kitchens to us, they explained how they work, they showed us everything they do, and then, at the end, they would still ask us: ‘What else do you want to know? How can we help?’ and also they wanted to know: ‘How do you work in Cuba? How do you do this? How do you do that?’ We really bonded.”

When asked why she agreed to participate in the exchange, chef and author Michelle Bernstein of Seagrape and Crumb on Parchment, didn’t hesitate: “How could I not?”

“I was born and raised here in Miami and while my background is Argentine, I could say I’ve been partly raised by the Cuban people here,” she said. “To be able to have [these chefs] here, to share with them even a little bit of what we do, and to have my people learn what they have to teach us, really moves me. They do so much with so little. That’s a great lesson.”

Watching cooks and assistants working under pressure in the close quarters of a kitchen is to witness a precisely choreographed, deceptively calm ballet. Even in the chaos of one kitchen at the Miami Culinary Institute, suddenly invaded by reporters and TV cameras, Alfonso, Smith and Calvo took time in their preparations to show students, some of them with just days of experience, basic techniques.

“We work with chefs all the time,” said chef Steve Sabatino, a Miami Culinary Institute instructor. “But this is very enjoyable because usually chefs come in and just do a demonstration and we watch; here we are cooking our food, they are cooking their food and you see our chefs working with them. Our students are getting to see top chefs from another country do their stuff. And [these chefs] might not always have the key ingredients, but they make it work and that’s the sign of a true chef: You make a phenomenal meal with what you have.”

In fact, the common themes in the conversations were challenges such as the inconsistencies of the market, the unpredictability, from day to day, of what may be available to them, and the lack of certain equipment. But rather than presenting it as a problem, these Cuban chefs seemed to shrug it off and look at it as creative opportunities.

“I always say that we are chefs, and being a chef is synonymous with creativity; so if today you can’t find tomatoes you use cucumbers, and if there is no cow meat you use pork,” says chef Gilberto Smith, owner of Pizzanella, which offers both pizza and Cuban fusion cuisine. He comes from a family of cooks; his grandfather Gilberto Smith Duquesne was one of the most important chefs in 20th century Cuba. Smith Duquesne was president of the Culinary Federation of Latin America and the Caribbean, a member of the French Culinary Academy — and mobster Meyer Lansky’s personal chef. “If you know your business, you manage. What worries me? Publicity. How do you promote your business.”

Smith’s timing was excellent as chef Alberto Cabrera, owner of Bread + Butter, was readying the opening of its Coral Gables location.

“I’m a pioneer in the area of private enterprise,” says Smith. “I might know something about cooking, although you never stop learning, but I really need to learn how to manage the business side: how you calculate costs, prices, inventory. If that part doesn’t work nothing else matters. Mr. Cabrera has been very helpful.”

Born and raised a Miamian of Cuban descent, Cabrera was once reluctant to participate in exchanges with Cuba.

“And I’m still not in agreement with certain for-profit culinary trips to Cuba,” he says. “But I don’t mind exchanging ideas and talking about how to better the situation of the people. The older generations on both sides are the ones still holding on to some political things. I think younger generations, both here and there, want change. When we sat down with Gilberto to talk there was no talk about politics. It was all about our industry and that´s how it should be: How can we help people there?”

Luis Alberto Alfonso Pérez, the most experienced of the visiting group and currently the chef at El Gringo Viejo restaurant in El Vedado, Havana, speaks like a weathered entrepreneur as he notes, “In Cuba there may be many challenges, but the main challenge is the human mindset. Whoever has a business, anywhere in the world, knows it … not because you have a business you are set. In fact, you have to work harder. You have more responsibilities.”

Yamilet Magariño Andoux, a chef who has specialized in pastries, is also a teacher, an author—“Como para chuparse los dedos” (“Finger Licking Good”)—and has a cooking show on TV. For her, the experience was positive at many levels.

“What we have seen are very professional kitchens,” she says. “You can see a very solid education. We need that in Cuba. We need to invest in teachers. But what I take most from all this is the friendships we´ve made, meeting these chefs, the exchanges we had, the sharing of ideas. We are taking all that back to Cuba. I’m going back with a full agenda, a book full of notes and ideas for the next three TV shows. This has been a great help.”

Fernando González is a Miami-based arts and culture writer. He can be reached via email at [email protected].

Recent Content

-

Communitiesarticle ·

-

Communitiesarticle ·

-

Communitiesarticle ·