Visitors play with architecture at Akron Art Museum’s interactive ‘Build It’ exhibit

Photo: A building block construction by Akron Art Museum staffer Dominic Caruso. Photo by Roger Durbin.

The title of “Build It,” an interactive exhibit at the Akron Art Museum, is not a direct reference to the old adage of “build it and they will come.” Metaphorically, however, that is precisely what this show does. One of the current, ongoing aims of the museum is to engage the community with its collection in innovative ways–an objective that is supported by a Knight Arts grant. And “Build It” speaks specifically to that goal.

According to the museum’s Director of Education, Alison Caplan, and its Associate Educator, Gina Thomas McGee, the Mary S. and David C. Corbin Foundation Gallery on the first level of the facility has recently been used for community-related, experimental ways of presenting parts of the collection. As McGee said in a walk-through interview, the exhibits to date have “always had a surprise” with them. She added that specifically they have had some “interactive component that is children- or family-centered.”

In “Build It,” floor space is dedicated to a collection of building blocks that can be used for creative play: Lincoln Logs, small magnetic pieces, larger-scale rubber shapes and the like. On the walls that surround this area are pieces of art from the museum’s collection depicting various architectural structures. As Caplan noted, the goal is for viewers to think about the idea of place.

The notion comes through even before entering the small gallery space. On the wall are two large-scale works from the collection. One is a photograph by Andrew Borowiec titled “Akron, Ohio” of a redeveloped neighborhood in the north side of the city. The work depicts buildings with singularly clean-looking lines and bright colors.

Andrew Borowiec, “Akron, Ohio,” 2006. Photo courtesy of Akron Art Museum.

Nearby on the floor of the entranceway is a big box of malleable blue shapes that can be fitted together. The title on the box says “Imagination Playground.” As we were talking in general terms about the exhibit, Design, Marketing and Communications Coordinator Dominic Caruso played around with some of the shapes, ultimately coming up with a large construction that had a serpentine look to it. What if, as Caplan and McGee might ask, the construction were really a building or a series of connected architectural spaces? That would lead to larger questions of function and purpose.

Those larger questions about architecture and sense of place are what drive “Build It.” Caplan and McGee surfed through online images of the collection, seeking out particular pieces that explore different aspects of architecture. They divided the images around four concepts pertaining to the use of building blocks to define space.

One section is called “Materials Matter,” in which the creators of the exhibit ask people to consider the need for either a short-lived construction or a building that is meant to last forever. Another section is called “Design Decisions,” in which the creator of the space needs to address issues of whether the building should be tall, like a skyscraper, or low-lying because of surrounding terrain and weather concerns. Still another section is called “Character Building.” It asks questions about ornamentation and luxury–like whether the walls should be curved instead of flat, or if there should be a roof-top garden.

The last section, “Shape Shift,” takes on basic elements that designers from children to professional architects have used: triangles, rectangles and squares. As McGee explained, most people have taken a triangle and put a square under it to draw their first house. In the exhibit, viewers are also encouraged to consider use of color and different kinds and combinations of building blocks to create more abstract places.

The art works Caplan and McGee selected prompt visitors to ponder the larger questions. Paul B. Travis, in his watercolor “Chartres Cathedral,” depicted a traditional Gothic structure by selecting views of parts of it and putting them together to create an abstract work. When juxtaposed, these partial components–half-circles of the round stained glass windows, half of a curved archway, pieces of the triangular spires from the building–create a more imaginary sense of place than a realistic rendering would.

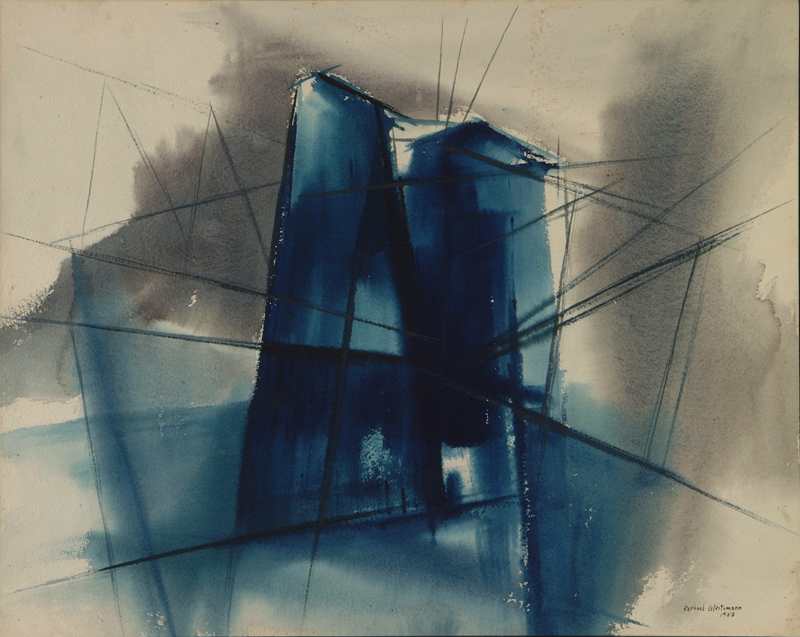

Raphael Gleitsmann, “Untitled,” 1953. Photo courtesy of Akron Art Museum.

Artist Raphael Gleitsmann, who often used watercolor to create a more true-to-life, folk-art interpretation of rural buildings, also dabbled in more abstract works. A 1953 “Untitled” watercolor shows a field of saturated blues on which he puts geometric patterns (some of them the familiar building blocks Caplan and McGee referenced) to give the idea of a very modern-looking building.

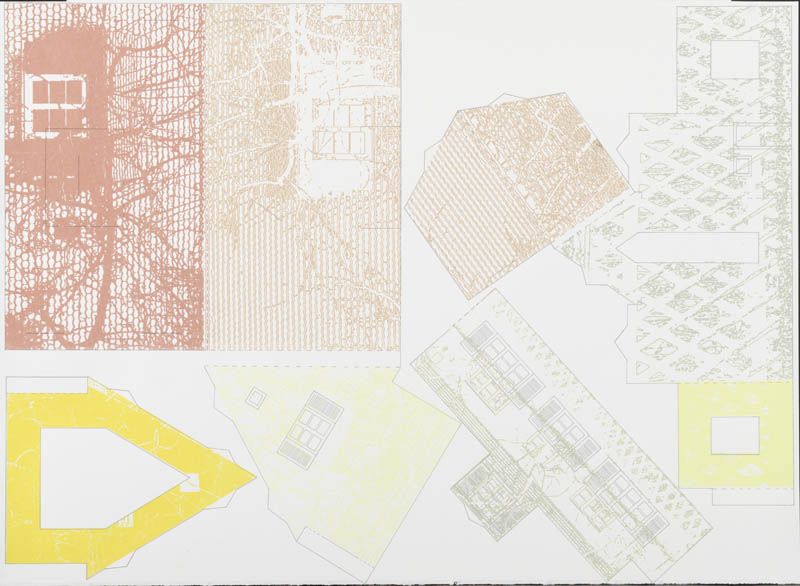

In another vein, Michael Loderstedt’s screenprint on paper, “HausBuch(e),” takes various parts of a building and shows them at odd angles. For example, he depicts a roof by looking down at the top of it, but having a sideways image of a wall beside it at a strange angle. However, were one to cut out the pieces and reshape them, as McGee noted, they would fold nicely into a building, floor and all.

Michael Loderstedt, “HausBuch(e),” 2009. Photo courtesy of Akron Art Museum.

Still more works address all of these concepts. The point, though, as Caplan and McGee said, is to get people to start using their fingers, play with building blocks and see what happens. The space helps set that in motion. Two area rugs have brick patterns on them. Small tables and chairs look as though they were made from Lincoln Logs. Scattered about are all the tools creative people at play will need.

Caplan and McGee said that visitors to the museum just seem to find the gallery and exhibit. Some tour guides bring groups through, but for the most part, visitors simply stumble across the space–and get to work. There are no particular directions sending them there. McGee commented that sometimes people will leave their constructions; whoever comes in next tears the creation apart and begins anew with his or her own vision. At other times, visitors will take apart their creations before they leave. While they are there, however, they get the opportunity to play creatively and learn something about the building blocks of architecture–and visual and three-dimensional art as well.

“Build It” will be on display at the Akron Art Museum through Sept. 13. General admission is $7 (free on Thursdays).

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·