Thriving with uncertainty: Lessons from a foundation learning together

This post is one in a series on what four community and place-based foundations are learning by funding media projects that help to meet their local information needs. All are funded through the Knight Community Information Challenge. Photo credit above: Kevin Bain. A video previously posted has been removed.

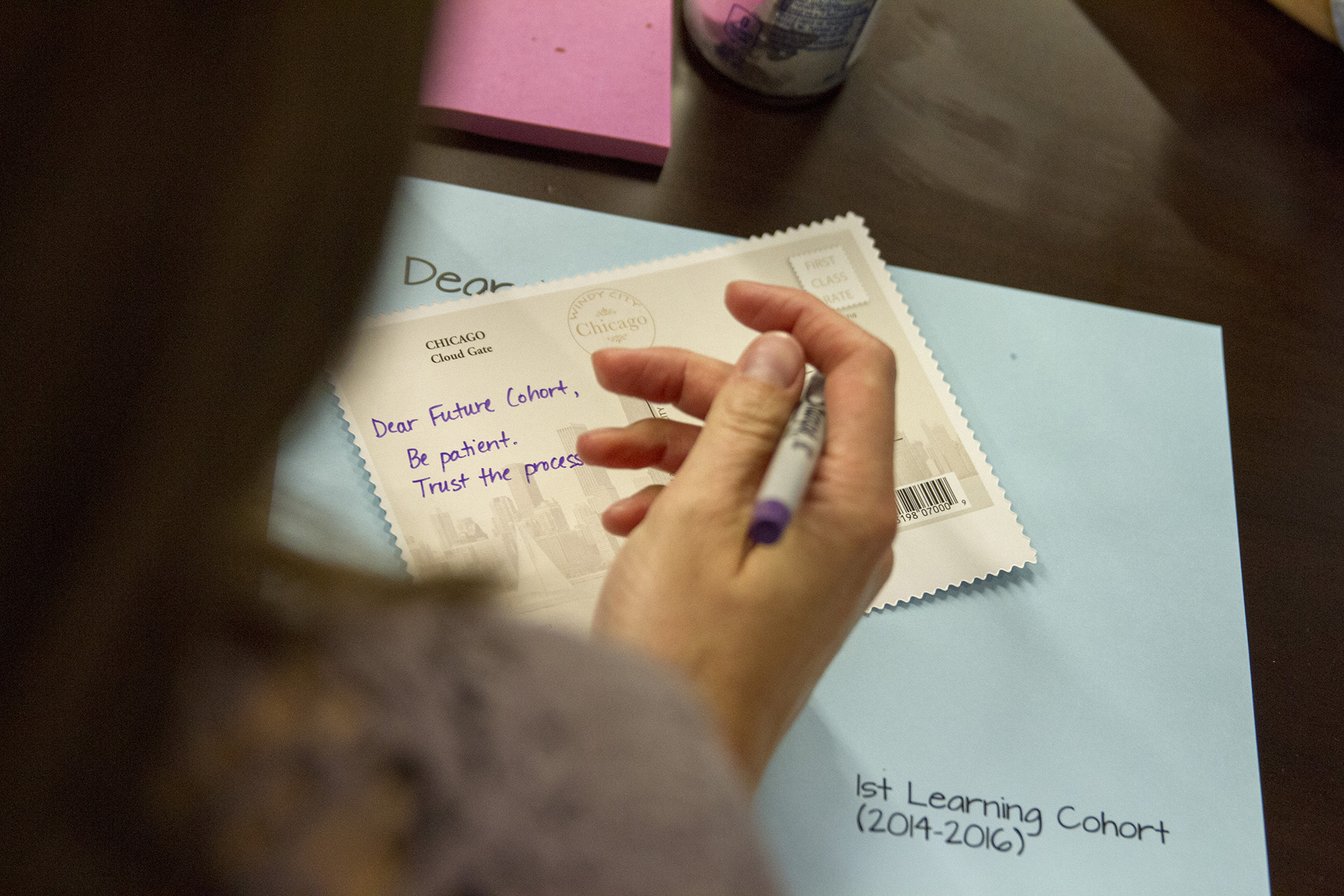

One year in, four foundations participating together in a learning cohort on local news and information solutions are beginning to share some lessons learned. One of the most important, the participants found, is the value of a thoughtful but fast-paced program of experimentation where failure is OK, because it provides quick learnings and insights.

Such ambiguity and risk taking is not the norm for many community and place-based foundations, but the learning cohort members think that it should be.

The four foundations – the Dodge Foundation, Silicon Valley Community Foundation, Incourage Community Foundation and the Chicago Community Trust – were winners of the Knight Community Information Challenge, which offered matching funding to local foundations launching news and information projects. Each was chosen to receive further funding for a deeper dive into local project. To help, staff members and leaders from each foundation participated in a series of design-thinking workshops, underwritten by Knight.

Here are some of the key learnings from the cohort’s year of working together:

Lesson: Design thinking holds promise

The deep-dive cohort workshops were led by Judy Lee, a San Francisco-based innovation trainer and consultant, who coached the four foundation teams on such core design-thinking concepts as rapid experimentation and prototyping so that ultimately a project is designed with (not for) stakeholders. Terry Mazany, executive director of the Chicago Community Trust, says he came to further appreciate the value of rapid prototyping and new ways to think about serving the foundation’s “customers.” The Trust already was incorporating design thinking into its operations, including with the Knight-funded civic tech organization the Smart Chicago Collaborative. But the cohort experience suggested that an even greater use of its principles is in order.

Daniel X. O’Neil, executive director of the Smart Chicago Collaborative,, confirmed that the cohort experience helped change how the organization approaches civic technology. In addition to working directly with developers of civic apps and websites, Smart Chicago has shifted to working more directly with the users of civic tech, getting them involved in designing civic digital services rather than allowing developers to try to divine what Chicago residents need. Bringing end-users into the design process at the earliest stages of planning – designing with, not for them – is a core tenet of design thinking.

Judy Lee, design thinking consultant, and Josh Stearns of the Dodge Foundation. Photo credit: Kevin Bain.

O’Neil and his team, as a result of participating in the learning cohort, also came to realize that their core focus should be more on Chicago residents who might be served by civic tech. They came up with the concept of taking a census of “outsider tech,” finding the many Chicago residents who are part of the tech sector (even if they don’t realize it) because they use technology in their careers and social lives. The team is now developing plans to identify, tell the stories of, measure the impact of and grow the capacity of the outsider-tech population. Design-thinking principles brought the Smart Chicago team to this shift.

Illustration: Kevin Bain.

Lesson: Foundations can move fast

At the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation, the mission is clear: Support the growth and maturation of a wide range of local-news operations, both for- and non-profit, in order to expand the troubled news and information ecosystem in New Jersey. Molly de Aguiar, program director for Media and Communications, says that accepting the Knight grant and participating in the learning cohort opened up conversations and allowed for experiments that wouldn’t have occurred under normal foundation operations.

The Knight grant and the cohort work provided new tools and ideas, and “gave us permission and the mandate to experiment, to figure out what works well, then put money into that,” she said at a September cohort meeting. “The conversations (to embark on experiments) probably wouldn’t have happened without this.” That included giving six local-news grantees “micro-grants” of $5,000 each to use on revenue-enhancing experiments. Those grantees were told to experiment and not be afraid to fail, as long as learning was the outcome.

Funding such experiments, because it was part of the Knight grant, did not have to go through the usual Dodge board of directors approval process, which can slow things down compared to the fast pace that de Aguiar and her team proceeded. “This was transformative to me personally,” she said; it “opened up my mind” about how to be a more creative and effective.

Lesson: Philanthropy can benefit from ambiguity

The design-thinking principle of rapid experimentation and permitting failure as a learning tool is counter to the culture of many foundations, says Josh Stearns, director of journalism and sustainability for the Dodge Foundation. Grantees typically come to the table with specific plans, which they are expected to execute successfully. But the uncertainty of encouraging and letting grantees experiment and even fail is “so much better” and portends more-effective outcomes.

The notion of allowed uncertainty also resonated with the Incourage Community Foundation. Corey Anfinson of the Incourage team thinks it’s “fabulous” not to have to know what the results are likely to be at the beginning of a grant. This is especially important in issue areas such as improving local information ecosystems and growing community engagement, which Incourage is trying to do in its hometown of Wisconsin Rapids, Wisconsin.

Lesson: Early experimentation is best when broad

For the new-initiatives team at the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, participating in the learning cohort expanded their notion of experimentation, as well as their openness to it. A year ago, the team was focused on experiments revolving around a single issue: Common Core standards for public education. Since, the team has forged a new path within the foundation: a program of rapid-fire experiments to better understand and address the information needs of Silicon Valley residents.

Mauricio Palma, director of initiatives and special projects, says that this represents significant cultural change for the leadership and employees at his foundation. “We’re asking them to move away from safe.” Palma cites the Silicon Valley – Knight partnership and the learning-cohort experience as opening up the foundation to the likelihood of significant change throughout the organization as its involvement in local news and information expands.

Lesson: The language of philanthropy needs to change

Much of the work of the deep-dive learning cohort involved opening up relationships with more people within their communities – in the vernacular of community foundations, increasing “community engagement.” As such, the language used to communicate with community members needs to be understandable. But there was much agreement among cohort members that this is a problem area for community foundations.

Too many people don’t understand what foundations do because external language often is laden with jargon that only philanthropy insiders understand. That includes grantees: Many of them are “bewildered by the language used in philanthropy,” says Molly de Aguiar of the Dodge Foundation. “We need to do a better job explaining what we do” to all audiences.

Lesson: Get out of the silo

The deep-dive learning cohort gave these four foundations an opportunity to get together in person and learn from each other. That’s not the norm, since most foundations are not natural collaborators, says de Aguiar. Her colleague, Josh Stearns, asks: “How do foundations show up for each other?” Foundations can’t afford to work in silos any longer, they say. By investing in the right relationships, “amazing things can get done,” adds Stearns.

Siloed organizations seldom solve big problems, such as how to create informed communities in an era of disruptive technological change and a struggling media ecosystem. “We’re living in a time of massive change,” says Terry Mazany of the Chicago Community Trust. “Philanthropy is not immune to the types of changes that we see around us.”

The collective wisdom of the deep-dive groups proved, on a small scale, the value of foundations working together on tough problems. Neha Singh Gohil, senior media fellow at the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, was enthused about the idea of focusing some of her time on this larger issue of how collaborations among foundations (and other partners) can push philanthropy forward in new ways. Learning from and being exposed to new ideas from the other cohort foundation teams highlighted the value of cross-foundation collaboration.

These four foundations are continuing their projects – and their learning together – through 2016.

Steve Outing is a Colorado-based writer and digital media consultant.

Recent Content

-

Community Impactarticle ·

-

Community Impactarticle ·

-

Community Impactarticle ·