Hyperart for hyperobjects: What Pipeline presents Olivia Erlanger’s ‘The Oily Actor’

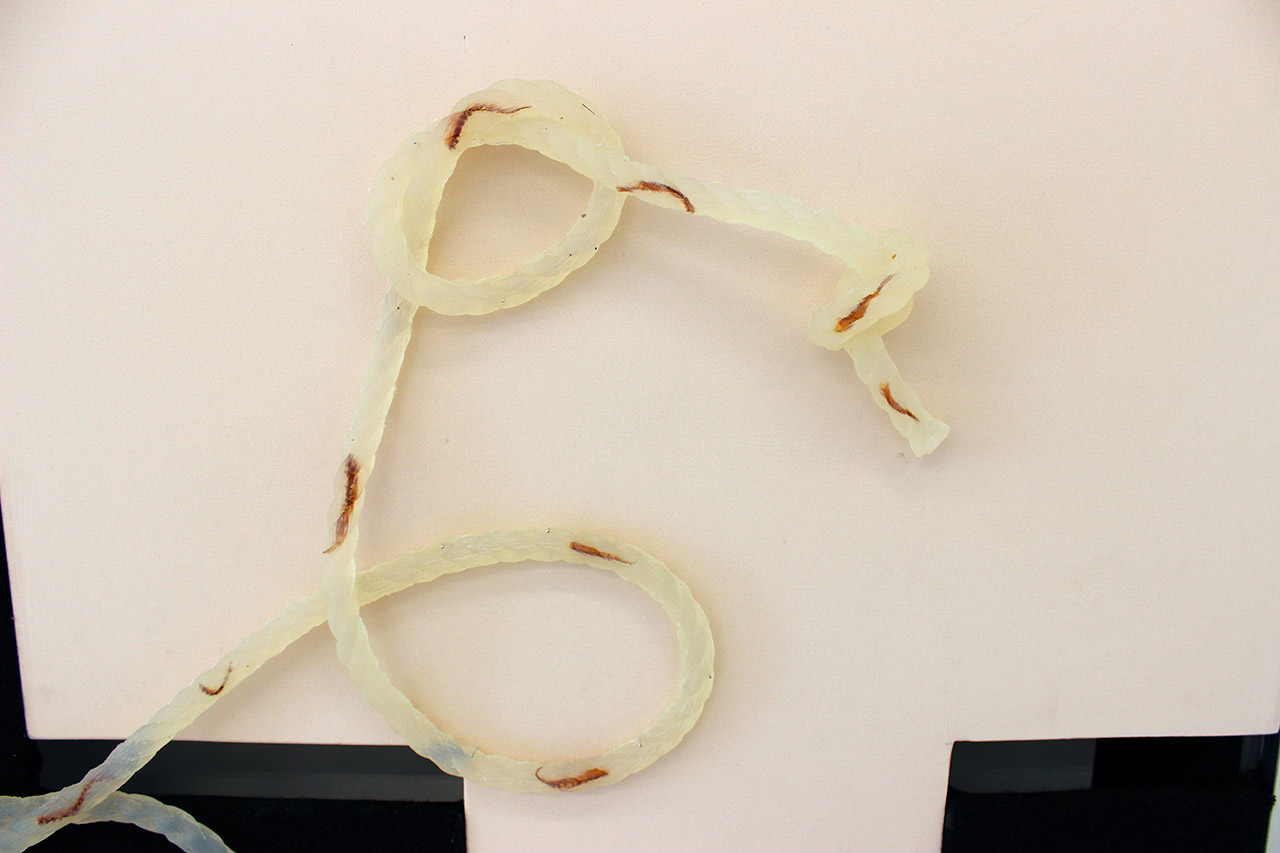

Above: One of Erlanger’s rafts.

“I had been looking around these ideas of systemic crisis, global financial crisis, which is what I came of age in,” said artist Olivia Erlanger during a conversation about “The Oily Actor.” This new body of work was presented at What Pipeline, a Knight Arts grantee in Detroit. “It was the most prominent dialogue in the house that I grew up in… Every dinner table conversation was about the economy, money and how everything is an illusion.”

“The Oily Actor,” which was on display through March 26 at What Pipeline’s unassuming gallery space off Vernor Highway, included an ambient sound piece and a floor installation, but focused primarily on three wall pieces that Erlanger refers to as “rafts.” Erlanger’s work draws together an incredibly dense array of source material, processing a prodigious reading list that includes Karl Marx, experimental science fiction writer Mark von Schlegell (“Raft for the Doll in Glass” is named for a character in his novel “Sundogz”) and philosopher Timothy Morton–as well as an equally vast range of physical materials.

“The Oily Actor,” installation view.

Her previous work has presented objects in architectural “scaffoldings,” which kept them quite spare and separate; within “The Oily Actor” we see Erlanger’s components pushing at the banks of their metal frameworks, overlapping and interacting in a manner that suggests an ecosystem of sorts. This maps well with her interest in Morton’s writings on “hyperobjects”–things so large and viscous that we can only consider them as abstract concepts. The two hyperobjects informing “The Oily Actor” are the global financial crisis and the state of ecological disaster being experienced worldwide. Climate is a perfect example of a hyperobject; unlike weather, which we are able to access merely by walking outside, climate remains entirely abstract, even as it slowly shifts in ways that will have tremendous impact on society and human existence. “It’s frustrating because we never give these things [hyperobjects] a language of volume or density,” said Erlanger.

Erlanger attempts to give these concepts a more immediate presence through her work, with careful attention to her source material–both physical and informational. The impact of the housing crisis, which greatly exacerbated an already unstable market in Detroit (and other places), is dealt with in a sound piece, “I Am No Viper, Yet I Feed.” This work utilizes live Detroit data points from the real estate valuation website Zillow to augment a 12-song playlist, creating a distorted ambient soundscape that continued to change throughout the run of the exhibit. Just as the abstract concept of debt can manifest in pressure or anxiety, Erlanger’s sound piece takes familiar pieces of culture and warps them into haunting dirges that suffuse the gallery in dread or confusion.

“Raft for the Doll in Glass (2016),” detail view.

If the concepts presented by Erlanger represent heavy and daunting challenges, the rafts nonetheless become vehicles for hope. This is an ancient vehicle, after all, and one perfectly designed to navigate the fluid density of the hyperobject, skimming the surface like a leaf on the wind. Like any good survivalist, Erlanger has packed these metal frames with supplies: wool, silk, spices, pollen. These suggest a practice of trade–and not just the human invention of exchange, initially facilitated by watercrafts like rafts; a trading economy, after all, was first perfected by nature. A section of honeycomb within one of the rafts reminds us that bees have been busily trading pollen for millennia, much to the benefit of humanity. Perhaps there is the suggestion that humanity’s salvation lies not so much in our distinctly human qualities, but those that we share with nature.

Whatever the message, this intense and lovely body of work presents a dense and difficult problem, and left this particular viewer feeling truly challenged to imagine solutions.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·