Compositional pioneer Oliveros featured at New Music Miami

When it comes to the heart of music, it comes to sound – sheer sound, away from categories, away from genre, away from top-10 lists and opus numbers and Billboard charts.

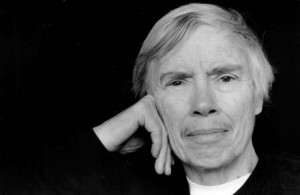

This weekend, the folks at New Music Miami host an American composer whose work has been about this fundamental aspect of the art of music for much of her career. Pauline Oliveros is a pioneer of electronic music, and has been a key figure in exploring its technologies since she ran the Tape Music Center at Mills College in Oakland, Calif., in the 1960s.

There’s a parallel there with Pierre Boulez, who was the chief figure in electronic exploration in France with IRCAM, the big French institute for the study of sound and composition. For Oliveros, the major development of her interest in electronic music and sound innovation has been the Deep Listening Institute, which mixes the ideas of listening, creating and meditating, all of it drawing from the basic fact of sound.

At Florida International University’s Wertheim Hall on Saturday, Feb. 19, the FIU Symphony, FIU New Music Ensemble and the NODUS and FLEA groups will perform three works by Oliveros – “New Sound Meditation,” “100 Meeting Places,” and a movement from “Four Meditations for Orchestra” – as well as pieces by Guillaume Cote, Jacob Cooper, Jordan Nobles and Morton Feldman (“Intersections”), whose slow soundscapes fit in well with Oliveros’ aesthetic.

We live in an unusual time compositionally, in which there has been a return to more traditional Romantic styles and approaches in new music, a phenomenon that has partly been a response to commercial music and also to audience indifference. Pauline Oliveros’ appearance is a reminder of a much more experimental time in composition, when it seemed likely that the practices of four centuries of Western music would be upended for good.

That hasn’t happened, but listening to the music of composers such as Oliveros and Feldman is a way to enter a totally different sound world in which the sheer fact of a note or a chord, a short motif or a rattle of percussion, means something in and of itself, and isn’t tied into a typical musical narrative. It’s the kind of music you might create when you’re simply sitting there of an empty day, looking outside at nature, holding an empty can or bottle and a stick, and trying to figure out how many sounds you can get out of the vessel, and hearing how those sounds make their impact in the world around you.

By saying that I don’t mean to make it sound childish or primitive. Quite the contrary: It’s only when you get rid of the traditional accretions of history and return to the sonic origins of music that you can create conscious art like this. It reflects a different approach to how we make music and how we present it, and there’s something restorative as well as challenging about it.

Saturday night’s concert offers an opportunity for adventurous listeners to see a pioneer of American composition and hear a remarkable brand of music that reimagines what can sometimes be an oppressively noisy musical universe.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·