Do universities hear the critics of journalism education?

Remember the scene from the movie Annie Hall, when everyone is in the theater line? An academic blowhard misquotes media scholar Marshall McLuhan. Woody Allen protests. Retorts the prof: “I happen to teach a class at Columbia… my insights into Mr. McLuhan have a great deal of validity… .” Says Allen: “Well, that’s funny because I happen to have Mr. McLuhan right here.” And into the frame walks Marshall McLuhan himself. He looks the prof right in the eyes and says: “You know nothing of my work … how you got to teach a course in anything is totally amazing!” Muses Allen: “Boy, if life were only like this.”

Unfortunately, life isn’t like that at all. And so it was the other day when the provost at Indiana University announced she was going to “improve” the university’s award-winning School of Journalism by running it out of Ernie Pyle Hall and mashing it into the College of Arts and Sciences where the scholars in charge will have their way with it.

The provost said the journalism education reform we’ve been writing about was part of the reason for change. Yet from all appearances, she knows nothing of our work.

We’ve argued journalism education needs to grow. At Indiana, the discussion is about attrition. We think journalism education should become more important. At Indiana, the school is losing independence. Journalism schools should be nimble. At Indiana, they’re increasing the layers of decision-makers. We say top professionals should be equal to scholars. They’ll bury the pros in a college run by scholars.

Is “reform” being used as a political excuse to demote the school? Why? Indiana isn’t tiny. It’s in the upper half of independent schools in terms of financial resources. Its writing quality is high, with its students winning Hearst Journalism Awards. It is weaker in broadcast and digital media (just look at the web site). That said, inventing the future of news can’t possibly be achieved by mashing the larger standalone schools into someone else’s college. It will come when leaders desire – as the president and deans have done from Arizona State University to New York’s Columbia University – to take a good school to a higher, greater level. The changes I’ve been describing, including a professional doctorate, are not what’s being discussed at Indiana.

This brings up a bigger issue. Is journalism education getting the message? We’ve been talking about four “transformational trends.” Great journalism schools 1. connect with the rest of the university; 2. innovate with digital tools and techniques; 3. master more open, collaborative approaches, and become not just community information providers, but “teaching hospitals” that inform and engage their communities.

Is that message getting through? The first reaction was: We’re doing it! But then schools showed us journalism with no engagement, which is pretty much like hospitals with doctors and medicine but no patients. When we explained, the second reaction was: We can’t do all this! If we teach gizmos, we can’t teach journalism. Wrong again. To teach journalism in the digital age you have to teach both journalism and the digital age — and use modern tools to do it. That’s why the schools that are serious about this are getting bigger, not smaller.

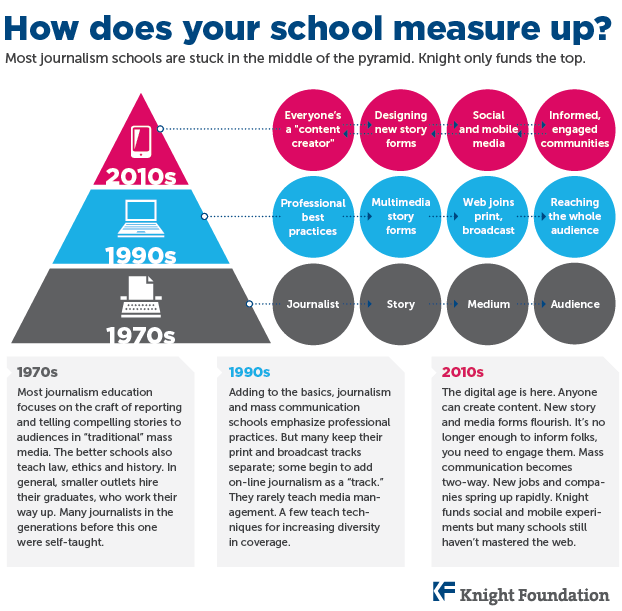

Let’s try the message again, this time with a graphic. Atop this blog you see three layers of journalism education, from craft training to professional education to the new, networked world.

You get to the top by doing each level well and continuing to move higher. Few schools have made it to the top. But some are doing great things. Teaching digital media literacy to a whole community. Teaching news literacy to 10,000 freshmen and sophomores. Team-teaching new app classes with engineers. Offering joint journalism-computer science degrees. Educating entrepreneurial journalists. Being the most important source of information and engagement in their communities. Some of that is described in the report on the Carnegie-Knight Initiative for the Future of Journalism Education.

Can journalism education keep up, with the ground shifting under it, with word people who need to become numbers people, with the bloodsport of developing new classes, with a lack of appreciating for professionals? How will it all come out?

On the one hand, journalism education leaders have rewritten accreditation standards into the digital age. They seem to want to track reform with improved surveys of programs and graduates. They are looking to the future at leadership meetings. On the other hand, j ed hasn’t coped with mobile and social yet, and now Google is coming out with media glasses. New techniques and technologies are born monthly and it takes two years to get a new class through. Major new forms of media arise in less time than it takes to get a PhD.

I doubt academia will handle the digital age well. It still hasn’t accepted that this is the biggest leap since Gutenberg conjured the age of mass media with movable metal type. Yet an America with fewer than 500-plus journalism programs would be just fine with me, so long as they get better. As Jason Robards (playing Ben Bradlee of the Washington Post) said in the movie All the President’s Men: “Nothing’s riding on this except the First Amendment of the Constitution, freedom of the press and maybe the future of the country …”

What kind of journalism school will Indiana become? The interim dean reports the provost wants it to be “breathtaking.” If she restores independence, shifts the unproductive people (including scholars) to other programs, rewrites promotion and tenure rules, builds a new digital facility, hires the best people and totally revamps everything that’s taught – boy, if life were only like this — well, that would be breathtaking.

By Eric Newton, senior adviser to the president at Knight Foundation

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·