“Dreamtigers” playing through March at the Detroit Puppet Theater

Did you know that just a couple blocks from the Detroit Opera House downtown, within walking distance of Comerica Park and Ford Field, there exists a puppet theater? Formally founded in 1998 by a group of artists and puppeteers trained in the former Soviet Union, the Detroit Puppet Theater is both an imaginative performance space and a veritable museum of vintage puppetry, featuring numerous displays of puppets from all over the world. This past Saturday I caught a showing of “Dreamtigers,” a family friendly production by the Detroit-based, internationally renowned Hinterlands Ensemble.

What most impressed me about “Dreamtigers” was how it appealed to the many children in the audience — who squealed with laughter throughout — without over-simplifying either the production or story. Children are intelligent and intuitive, with an ability to tackle concepts far more complex than they’re given credit for. Too often, entertainment aimed at children is dumbed down and saccharine sweet — pandering vehicles used to deliver pat, two-dimensional lessons. “Dreamtigers” — though it begins with basic elements of slapstick comedy to engage the children, and adults, in attendance — goes on to unfold a dreamlike narrative that is imaginative, subtle and eerie, and one which continues to build in suspense as it progresses.

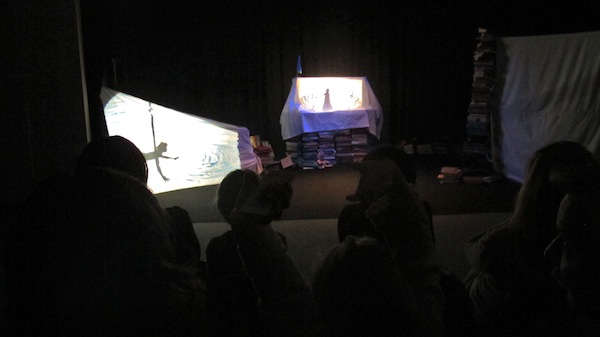

The performance is also unique in its use of low-tech, analogue techniques, such as shadow puppets, which is rare in contemporary entertainment. We’ve become so accustomed to movies and television shows that saturate the screen with whizz-bang digital effects, it’s easy to forget how immersive and effective relatively simple, time-honored techniques, like shadow puppetry and live storytelling, can be. One might think it would be hard to entertain today’s kids, whose idea of entertainment is the latest summer blockbuster featuring eye-popping three-dimensional visuals and a frenzied and exhausting pace of action, but as the lights came up after the performance, I witnessed a child seated in front of me turn toward her mother and, with bright and eager sincerity, say, “That was fun, Mommy! Did you like it?” Really, nothing more needs to be said.

“Dreamtigers” runs Saturdays in March — the 17, 24th, 31st at 2 p.m. — and Thursday, March 15 at 10 a.m. Seating is limited, so be sure to RSVP: 313.961.7777.

The Detroit Puppet Theater: 25 E. Grand River, Detroit, Mich. 48226. 313.961.7777 Puppetart.org

After the show I caught up with Richard Newman, co-founder and co-director of The Hinterlands Ensemble, and got to ask him a few questions. The result of our conversation follows:

Jeremy Schmall: What led you to found The Hinterlands Ensemble here in Detroit? Richard Newman: We founded The Hinterlands in fall of 2009 while we were working in Kalamazoo, Mich. We spent the next year semi-itinerant, spending two months in Kalamazoo, about nine months in Milwaukee, and two months in Pristina, Kosovo before settling in Detroit. I had visited Detroit in 2009, right before founding The Hinterlands and was immediately drawn to the people, the history and the culture. We came to Detroit three more times over the next year, making an effort to see different things and meet a variety of people. I’m a huge Detroit techno fan, so music certainly had something to do with my initial attraction to the place, but it really came down to the conversations we had when we visited. Obviously, there were other factors at play — low cost of living, affordability and availability of space etc. — but those factors were less important to us than the people who were already living and working here. JS: On the surface it might seem disadvantageous for your ensemble to be based in Detroit, but I’d be willing to bet there are actually major advantages. What are some of those advantages? RN: Well, as I already mentioned, affordability is a big one. We pay very little to live, which allows us to focus on our work without worrying too much about making rent. We’ve managed to spend a good bit of our time surviving just from our performance work, which would be very difficult in another city. The low cost of rent has also allowed us to tour our performances, which is a major source of income for us, without having to hustle to find a subletter. It’s also allowed us to house visiting artists for a specific project. We’ve also never had any problem finding space for rehearsals or performances, which in other cities can be a major issue.

The Hinterlands are an experimental theatre ensemble, and as such, we have a smaller audience potential than, lets say, a major sports team or even an opera company. So, while we are by no means the only game in town as far as experimental performance goes, there are less companies like ours than in other cities with similar populations, which gives us an advantage over a company in New York or San Francisco or even in a smaller city like Austin or Portland.

The main advantage for us has been the ease of collaboration across disciplines — which has more to do with the attitude of the artists who live in Detroit than any demographic consideration. The way we’ve been able to collaborate with different kinds of artists — designers, musicians, architects, metalworkers, puppeteers — has been really wonderful for us. It’s really changed our work and forced us to grow in surprising ways. JS: I really enjoyed the shadow puppets you used in the performance of “Dreamtigers.” Do you typically use shadow puppets in your performances? RN: We try to incorporate a variety of performance styles in our performances, which usually includes some form of puppetry, although not always shadow puppetry. Our last performance, “Manifest Destiny! (there was blood on the saddle)” used life size puppets/dummies as well as a toy-theatre section. We also use everyday objects in a way that could be described as puppetry. Our last use of shadow puppets was for a section of “Isaac Newton is Our DJ,” which we performed in 2010. There was a shadow puppet section depicting a fictionalized version of Isaac Newton’s biography. JS: Your use of more low-tech/analogue effects in “Dreamtigers” is in stark contrast to the kinds of visual entertainment we’ve grown accustomed to, such as 3-D movies packed with CGI effects. Would you say your ensemble is part of a larger movement toward the use of more stripped-down, analogue elements? RN: Ours is definitely a “Poor Theatre,” and I don’t mean that only in terms of our limited budgets. We put our focus on the art of the performer and what the basic relationship is between performer and audience. This is not to say that we don’t like technology, we definitely do. The way we run sound for “Dreamtigers” is pretty high tech actually — using computer software, midi controllers and DJ technology to create and arrange the sound live. I think for everything we choose to use in a piece we examine whether it is going to bring us closer to this basic relationship between the performer and audience or take us further from it.

In terms of a larger movement, I do think our work is a part of a movement in the art world to acknowledge the importance of craft, in addition to the conceptual. I think it’s natural that as we live more of our lives online, that we would want to be able to make and see work that we can hold in our hands, so to speak. That’s the unique thing that live performance has to offer — the bodies of the performers and the objects they interact with. You don’t get more analogue than that. JS: You mentioned quite a few literary titans — Octavio Paz, Jorge Luis Borges, Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Julio Cortazar — went into the writing and story development of “Dreamtigers.” What elements were drawn from these writers? RN: We used a short section from “One Hundred Years of Solitude” to create the framework of the story of “Dreamtigers.” The central image of the piece, and the title, is taken from the Borges short story “Dreamtigers.” The setting and character relationships are a mash up of “Bestiary” by Cortazar, “One Hundred Years of Solitude” by Marquez, and just about every story by Borges that mentions a library. We pulled images and characters from “My Life With the Wave” by Paz, and other stories by Borges and Marquez, as well as some traditional folktales, like the story of La Llorona. We threw all of these things into a pot, added some garlic and bay leaves and voila –“Dreamtigers!” JS: How conscious were you throughout the production in being sure the performance appealed to children on a gut level, but also told a complex and challenging story in a way that many family friendly productions shy away from. RN: This was pretty intentional, but also instinctual. We didn’t use focus groups or anything. For the humor, we looked at things that we found funny from a visual/rhythmic perspective, understanding that these elements should be funny to both kids and adults. Everyone, all across the world, laughs when someone trips, falls and recovers. It is pretty much universal. So using this kind of comedy is a way to give kids, and adults, a way in. Once you have people laughing, they are pretty much willing to go anywhere with you. In terms of the complexity of the story, I tried to think back to how I thought as a kid, and the kinds of games I played. I was an only child, and I created these incredibly complex story lines for my stuffed animals, with family dramas and histories, lengthy plots and subplots and even multiple levels of reality each with their own laws and circumstances. Our story is pretty simple compared to the imaginative worlds created by children.

JS: I noticed that one of your previous productions, “Manifest Destiny! (there was blood on the saddle)” was inspired in part by Cormac McCarthy and William S. Burroughs. There appears to be a through-line of deep literary influence in your ensemble’s work. Does your ensemble (or you) also write other kinds of literature, or does the influence get mainly channeled into playwriting? RN: We have a lot of influences, ranging from great works of literature to rather embarrassing pop cultural obsessions and completely obscure subcultural art forms. So, while there is a thread of literary influence in our work, it is one among many. Also, we don’t really consider ourselves playwrights. We create performances but we do this through a variety of means, writing being only a small part of the process. We don’t ever sit down and write a script. We create on our feet, engaging in lengthy periods of physical training and improvisation as well as character and image development, all very much outside of a traditional playwriting context. The text almost always comes last, sometimes later than we are even comfortable with. For instance, the action and images for the wave and for La Llorona came before we even had a solidified storyline. Most of the actual dialogue and narration came in the last two weeks of rehearsal, whereas we had the core images and characters a month before that. It also bears mentioning that the process for “Dreamtigers” — lasting roughly six weeks before opening — is a drastically shortened version of our regular process, which spans a year at least. Also, we continue to work on the piece throughout the run — changing text, altering the action and continuing to develop the design as we go. JS: What’s in store for the near-future of the Hinterlands Ensemble? RN: March 28 we are curating an event at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit [a Knight Arts grantee] — Drive-In Radio Theater, an electromagnetic evening of eclectic live performances in the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit parking lot broadcast to your car radio. Over the summer we’ll be in residence for six weeks at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, holding public rehearsals and performances in the galleries and throughout Detroit and conducting a two-week youth theatre program. The six-week residency will be the beginning of a long-term project investigating American Vaudeville and subculture premiering in 2013. We’re also planning on remounting “Manifest Destiny! (there was blood on the saddle)” in the fall of this year, so be on the lookout for that. JS: If there were no limits whatsoever, what would the Hinterlands Ensemble produce, and what would that production look like? RN: First of all, we’re always going to do the pieces we want to do regardless of resources. In that sense, the only limit is the imagination, and I believe that the imagination is infinite. Also, it’s hard to talk about what a piece would look like before you begin working on it — and as I’ve seen over and over, more resources don’t always yield better results. So, if someone gave us a bottomless pit of cash and resources right now, we would still continue to work on our next project exploring Vaudeville and subculture. Of course, certain things would change — we would no longer have to write grants or hustle to get paid — but I hope that the basic thrust of the work could be the same. I think that we would work with more artists, try to collaborate with as many people as possible, both in terms of our own development and the creation of the piece. We would also be able to more deeply investigate both the traditional form of Vaudeville and the myriad forms of American subculture through research expeditions that are currently outside of our reach.

On second thought, I think we’d choreograph dances for vacant houses that we convert into fully transformable amphibious robots, performed on the Detroit river for an audience of two people —one in Detroit and the other in Windsor. Matthew Barney, eat your heart out.