In U.S., Most Oppose Micro-Targeting in Online Political Ads

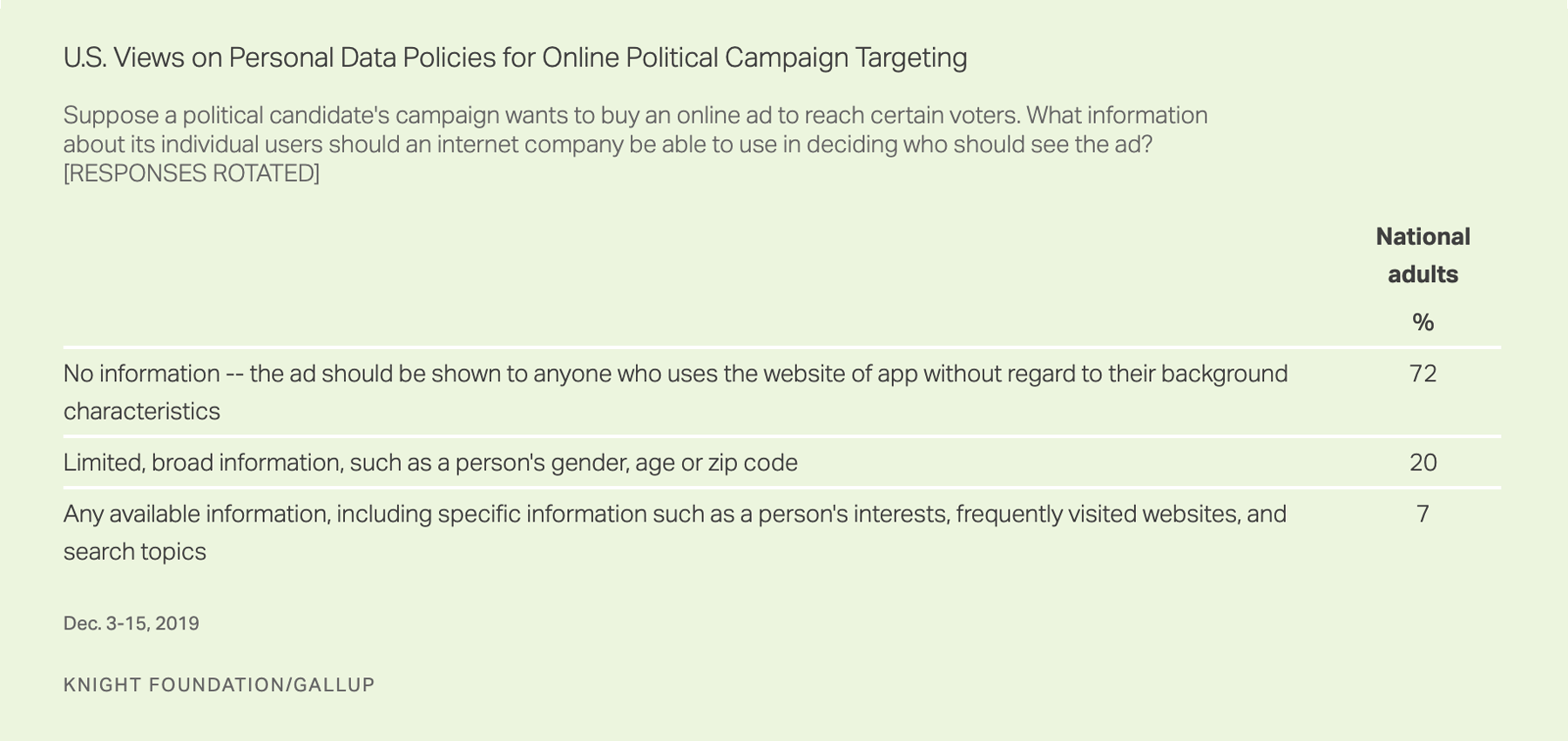

WASHINGTON, D.C. — In the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and Gallup’s latest research, a solid majority of Americans do not want political campaigns to be able to micro-target them through digital ads: 72% say that internet companies should make no information about its users available to political campaigns in order to target certain voters with online advertisements. This view is shared roughly equally by Democrats (69%), independents (72%) and Republicans (75%) alike.

One in five U.S. adults are in favor of allowing campaigns access to limited, broad details about internet users, such as their gender, age or zip code. This is in line with the policy at Google, which has reined in the scope of information that political campaigns can utilize for targeting.

Meanwhile, 7% of Americans say that any information should be made available for a campaign’s use. This is in line with targeting policies at Facebook, which has not put any such limits in place on ad targeting. Facebook does give its users some control over how many ads they see.

Websites frequently track users’ data — and Americans are aware of this: nearly all say they believe that Facebook and Google (97%), Amazon (96%), and news sites or apps (88%) collect data on their browsing history and purchasing habits. Internet technology companies have used user data to target and tailor political ad campaigns in the past — providing a valuable tool for political campaigns in recent election cycles.

These data, recorded in a Knight Foundation-Gallup survey conducted Dec. 3-15, 2019, come as major tech companies take differing approaches to political advertisements in the midst of the 2020 presidential race.

Most Want Campaign Ad Buyer, Cost and Target Audience Disclosed

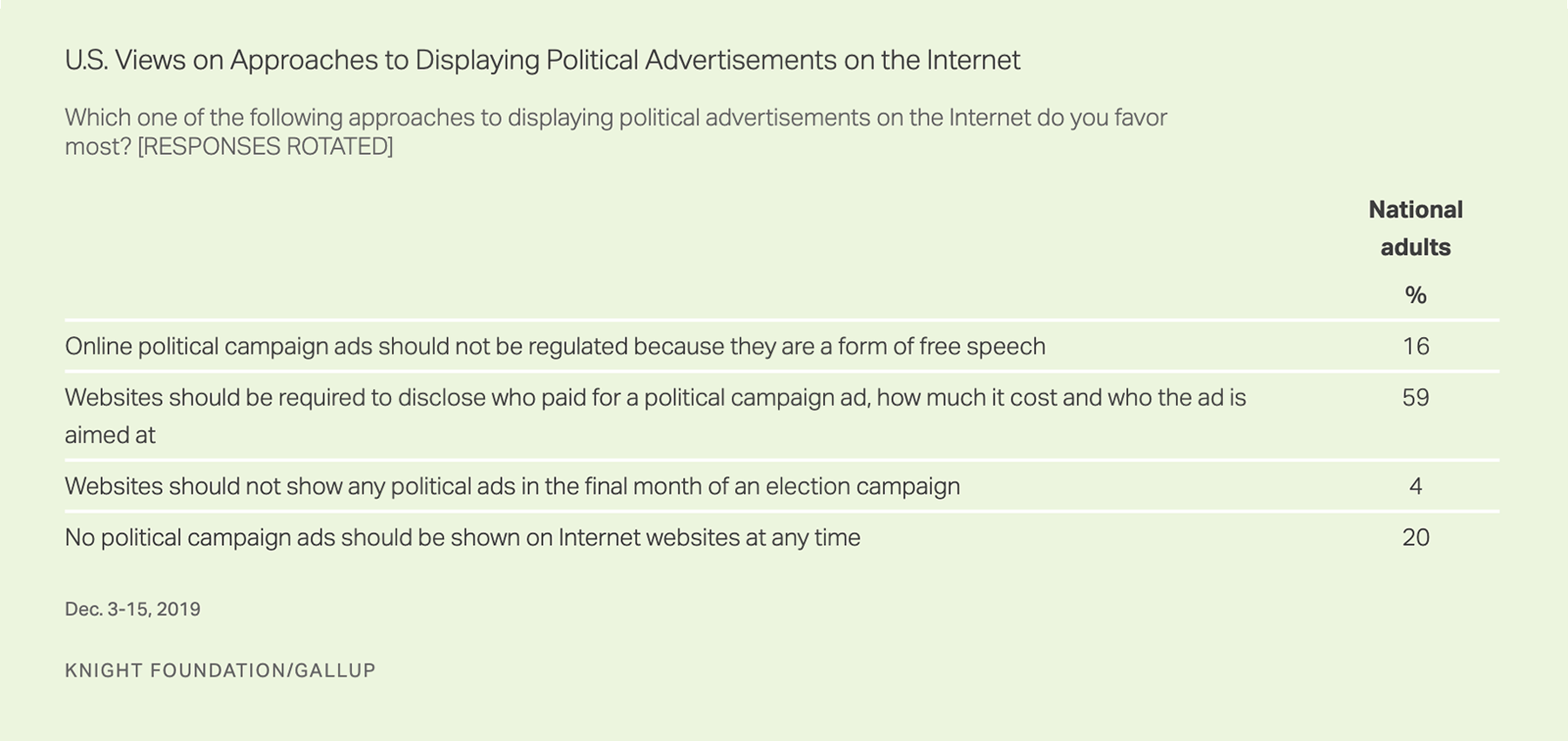

When asked to choose among four approaches websites could take in displaying political advertisements, Americans (59%) are most likely to favor websites showing ads, but with the companies disclosing who paid for the ad, how much it cost, and whom the ad is aimed at.

But sizable minorities, totaling about one in four, prefer opposite approaches in absolute terms: 20% say no campaign ads should be shown on any websites at all — the policy recently adopted by Twitter — and 4% say that sites should not show political ads in the final month of an election campaign. Sixteen percent say campaign ads should not be regulated because they are a form of free speech.

Democrats (28%) are somewhat more likely than Republicans (18%) to favor banning political ads outright or in the final month of an election campaign. Meanwhile, Republicans (29%) are much more likely than Democrats (4%) to say that campaign ads should be unregulated because they are a form of free speech.

Majorities of Americans Want Misinformation Bans in Online Political Ads

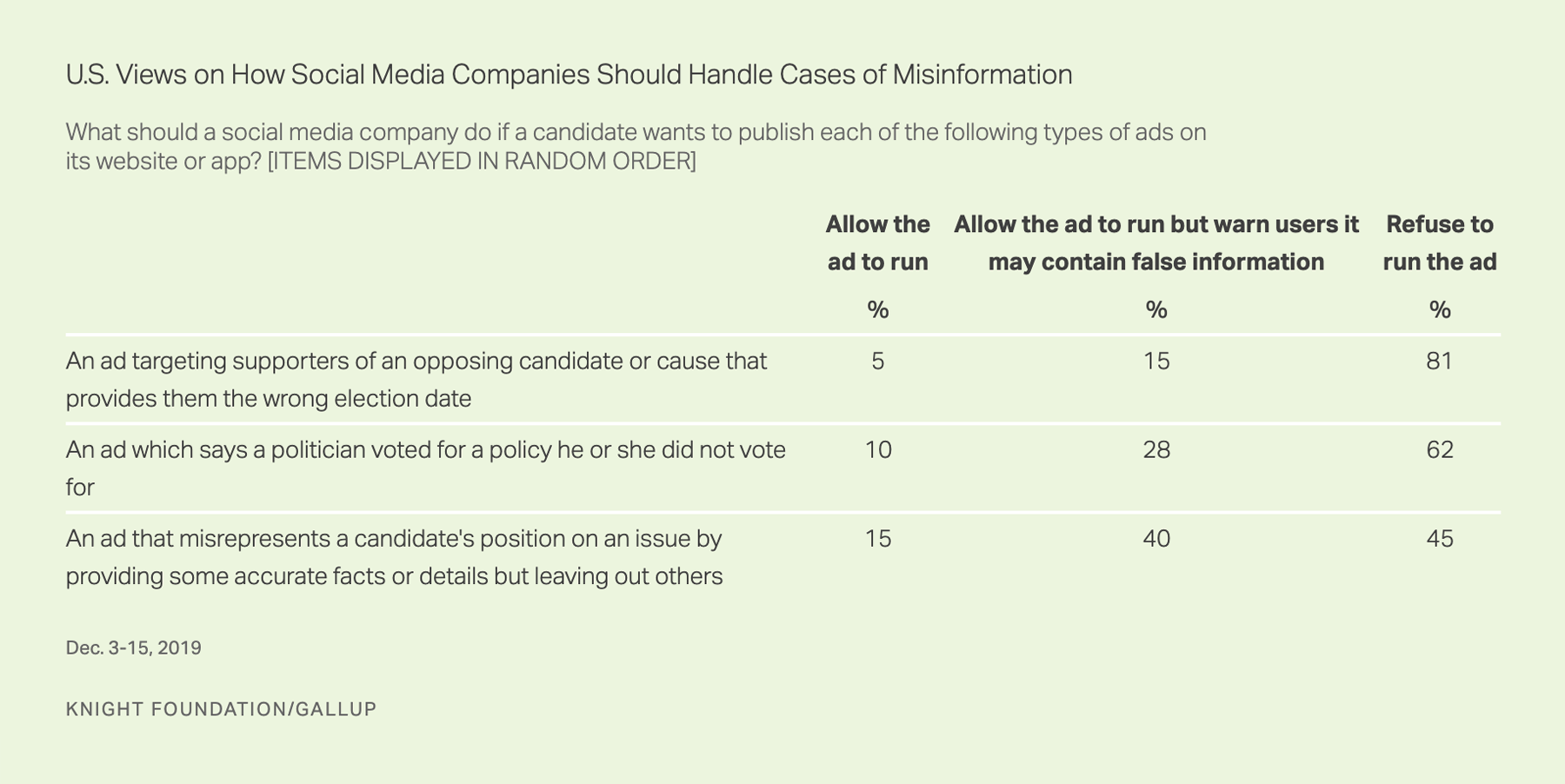

Solid majorities of Americans say that social media companies should ban misleading content in political ads, including those that would target supporters of an opposing candidate and provide the wrong election date (81%) or ads that say a politician voted for a policy they didn’t actually vote for (62%).

However, views are mixed on how social media companies should handle misrepresentations or omissions of facts — leaving online tech companies to make their own decisions on how to handle these gray areas.

Forty-five percent say such ads should be refused, while 40% say they should be allowed to run with a disclaimer that the ad may contain misinformation. Fifteen percent say the ad should be allowed to run unfettered.

Though some Americans believe that internet companies review political ads to ensure appropriateness (40%), most believe that websites show the ads without reviewing them first (59%). Industry policies on political ads vary from company to company.

Google’s policy forbids “demonstrably false claims,” though examples of this policy falling short of preventing misinformation have been raised. Facebook does not fact-check ads from politicians, though the CEO did say in a congressional hearing in the fall that ads with incorrect election dates would not be allowed. Meanwhile, Twitter has opted not to run political ads on its platform, including those by candidates for office, political parties, and elected or appointed government officials.

On the whole, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to favor stronger policies regarding content in political ads:

- Nine in 10 Democrats (91%) say an ad targeting an opponent’s supporters with an incorrect election date should be refused to run, compared with 73% Republicans.

- Seven in 10 Democrats (71%) say an ad that contains an inaccuracy about a politician’s voting record should be refused, while half of Republicans (55%) agree.

- Half of Democrats (50%) say an ad omitting some details about a candidate’s position should be refused while 41% Republicans agree.

Bottom Line

As policies surrounding online political ads are debated on Capitol Hill and in Silicon Valley, a presidential campaign is unfolding, with candidates spending hundreds of millions of dollars in online political advertising. And although legislation is currently under consideration, in the absence of federal regulation, the tech giants are making their own policy decisions.

Among the American public, however, there is broad consensus favoring limitations on microtargeting and misleading information in political ads.

Survey Methods

Results for this Knight Foundation/Gallup survey are based on internet interviews conducted Dec. 3-15, 2019, with a random sample of 1,628 adults, aged 18 and older, living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia who are members of Gallup’s panel. For results based on the total sample of national adults, the margin of sampling error is ±3 percentage points at the 95% confidence level. All reported margins of sampling error include computed design effects for weighting.

Justin McCarthy is a journalist and analyst at Gallup.