Pop Up Archive gives a new voice to sound on the Web

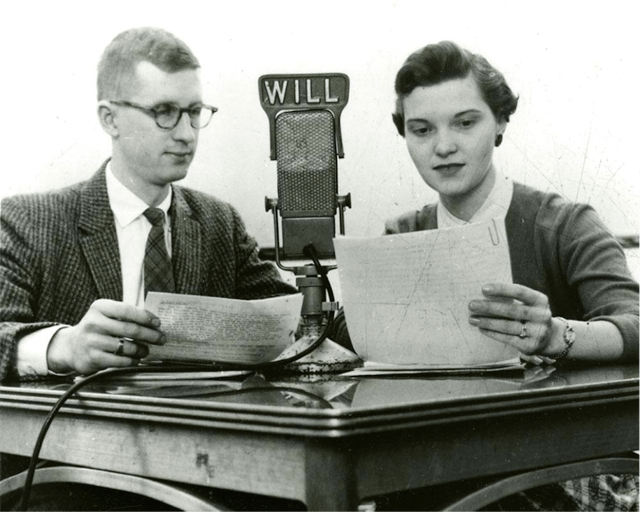

Pop Up Archive’s ever-growing collection of public sounds features Pacifica Radio Archives, Illinois Public Media, Studs Terkel and many others. Photo courtesy of Illinois Public Media.

Anne Wootton and Bailey Smith are co-founders of Pop Up Archive, a winner of the 2012 Knight News Challenge: Data. This week they are launching the service, which helps journalists, archivists and others store, find and reuse sound.

When Pop Up Archive was born, our goal seemed simple: to help audio producers organize their archives and create searchable sound. As we launch Pop Up Archive publicly, our goal has grown much bigger.

We want to make it easy for all storytellers to find and reuse recorded sound. Now, anyone can visit popuparchive.org to make audio findable through auto-transcription, auto-tagging and easy-to-use sound management tools. As we onboard audio collections large and small, we’re gathering sounds from around the world — and they’re all waiting to be discovered.

Among the voices: Buster Keaton explains silent film captioning to Studs Terkel in an age of entertainment far removed from today’s digital marketplaces. And a simple search across the public archive for a term such as “future” turns up results that span a Y2K apocalypse-centric radio broadcast from WBUR in 1999, Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel telling a local reporter about his plans for the city, and a recent California Report episode on the future of the online currency Bitcoin.

But we can’t do it alone. We started out as aspiring journalists, but we found our calling making tools to help journalists. Since winning the Knight News Challenge in 2012, we’ve built lasting partnerships with some of the most exciting, forward-thinking media organizations in the country. With the Public Radio Exchange, our co-conspirators and the best source of technical expertise we could hope for, we’ve made thousands of hours of sound searchable from an inspiring variety of media producers and oral history collections.

Rewind: Audio, a dying medium?

But let’s pause (pun intended; please forgive us) for a moment. Who cares about sound, anyway? Isn’t radio in its death throes?

It’s true that video, not audio, has received the lion’s share of attention on the Web—YouTube and Netflix are obvious examples. But the spirit of radio still plays a big role in news and entertainment: We can’t watch a screen while we’re driving or going for a run. As the Internet makes it into our pockets and terrestrial broadcast industries tremble with uncertainty, audio maintains a particular hold: Nearly a million people download each “This American Life” podcast, and SoundCloud has more than 20 million members.

In his Wired article, “The Web Is Too Quiet. It’s Time to Pump Up the Volume,” Clive Thompson writes: “To really unlock the informational power of sound … we need more tools to make it plastic, parsable, and findable.” In hour after hour of user research, we watched reporters scrub through audio files, wasting precious time trying to quickly locate the quotations they need for blogging and Web production. Today’s journalists — and tomorrow’s scholars — shouldn’t have to rely on their memories or YouTube to find audio.

It’s not a question of what to save; digital storage is only getting cheaper. It’s a question of how you find material once you’ve stashed it. Everyone is reluctant to pay the “future tax” of organizing up front, so audio files end up forgotten on hard drives and servers. Today, it’s easier to lose a WAV file than a cassette tape. So, how do we better access these non-text-based, opaque media formats? How do we integrate archiving with production without trying?

Fast forward: The future of sound

It’s audio’s turn. We’re on the frontier of searchable, data-rich sound — and affordable tools to make that happen. Easily indexed and organized sound means quicker workflows, new access to source material, rediscovery of forgotten voices, and revelations of latent patterns in audio.

Beyond all that data mining, we’ve been building a community for education, discussion and troubleshooting about the future of recorded sound on the Web. By plugging in with national digital preservation efforts, we’re helping content creators and scholars find previously trapped sound, such as the decades-old archive of Illinois Public Media at the University of Illinois and the more than 50,000 historic recordings housed by the Pacifica Radio Archives, the oldest and largest collection of public radio programming in the United States. We’re engaging with newsrooms, too, helping organizations such as the Center for Investigative Reporting revisit and reuse source material as they produce new work.

Audio shouldn’t be locked up in black boxes or proprietary systems. Pop Up Archive can open the door for real audio innovation by enabling crosswalks to and from other Web services such as the Internet Archive, Amara, SoundCloud and the Hyperaudio Pad envisioned by developer and audio futurist Mark Boas. By tethering these types of Web tools, we’re enabling a new generation of indexing, preserving, remixing and distributing sound.

If we’re going to build a bigger, noisier future, let’s do it together.

Pop Up Archive from Mario Furloni on Vimeo.

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·