Why combatting fake news requires people and technology — working together

Concerns about the spread of misinformation online have raced into crisis mode.

The European Commission has convened a working group dedicated to studying the issue and making recommendations. Major social media companies now routinely provide public updates on their efforts to combat the spread of “fake news” through their services. Just last week, Twitter announced new enforcement actions to target inauthentic and automated accounts. The week before, Facebook announced a “war room” to detect and combat coordinated efforts to manipulate information during the 2018 midterm elections. This past summer, a United Nations investigation into ethnic violence in Myanmar suggested that Facebook was a deliberate tool used by the military to spread inaccurate information about the Muslim Rohingya minority, and may have contributed to violence. Facebook responded by banning the generals from the platform.

These few examples underscore not only the concern that the internet and social media may be rife with deliberate efforts to deceive, but just how hard it is to address the challenge. The stakes are high.

We know that the problem is the product of both technology and human behavior. It is people who generate efforts to dress up inaccurate and misleading information as creditable “news.” But it is technology – primarily in the form of social media, but also through automation (“bots”) – that weaponizes at a larger scale these malevolent (or misguided) impulses.

So, if this is a human problem and a technological one, what about the solution? Can technology address our misinformation problem, or does it come down to people and what they do or don’t do?

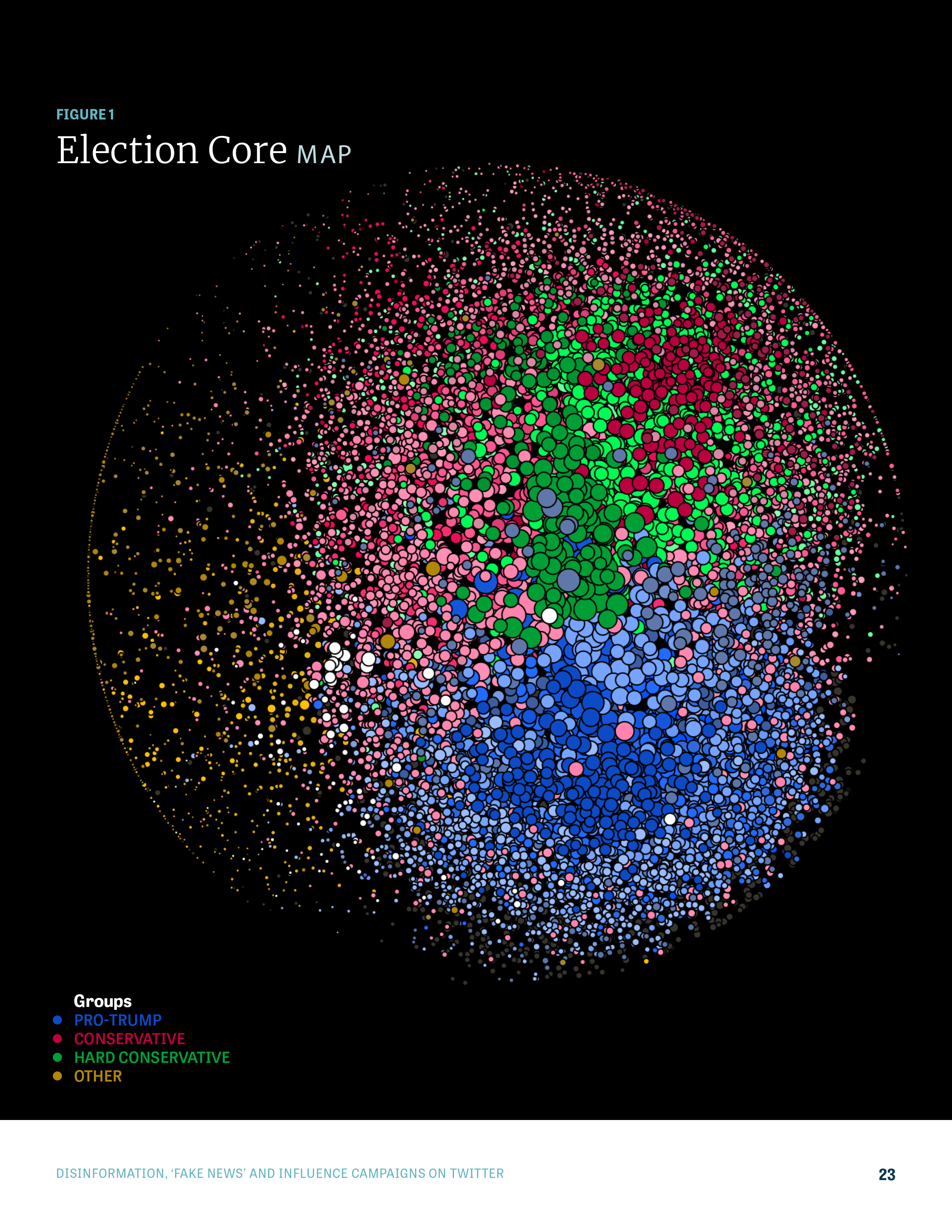

Knight recently commissioned a report from researchers Matthew Hindman of George Washington University and Vlad Barash of the firm Graphika that sheds some potential light on this issue. In one of the largest studies of its kind, the report analyzed Twitter activity before and after the 2016 election to identify how misinformation spreads across the platform. (Because Twitter data is much more readily available than other social media services, it is often the platform of choice for researchers).

A few findings stood out.

First, the report found that the points of origin for misinformation were highly concentrated. Just 10 large sites accounted for 60 percent of the news links to misinformation (and 50 sites account for 89 percent).

Second, using various models, the researchers estimate that anywhere from a third to two-thirds of Twitter accounts spreading misinformation are automated accounts or “bots.” That is, they are not real people but computer programs designed to interact with other Twitter users in particular ways.

Third, the report looks at a notorious source of misinformation during the 2016 campaign, The Real Strategy, and documents the impact of a concerted response. After the election, The Real Strategy’s Twitter account was deleted and a coordinated campaign to blacklist the site led to a 99.8 percent drop The Real Strategy’s reach.

If you’re a glass half full person, these findings suggest a few bright spots. First, misinformation isn’t “everywhere,” even if it’s prevalent. Rather, it’s originating at known points that can be identified and potentially targeted. Second, coordinated action that brings together technology tools and human tools can potentially have an effect. The example of The Real Strategy may point the way to a human-computer symbiosis, in which we use computing power to sniff out and eliminate sources of misinformation, and then rely on well-informed people to spread the word, blacklist and ignore the worst purveyors of falsehoods.

If you’re a glass half empty person, you’ll note another of the report’s findings — namely, that many of the most significant drivers of misinformation were highly durable and maintained their reach well after the election.

The bottom line is not new to us. Reaping the benefits of the internet and social media while avoiding the costs is a work in progress. It requires leadership from big technology companies, from governments and from people who will need to better navigate information online.

Getting our arms around this challenge is tough. But our democracy depends on it.

Go to kf.org/misinfo for more on the report and tune into the Zig Zag podcast, which will be exploring what these findings mean for addressing the spread of misinformation in its next two episodes.

-

Journalism / Article

-

Information and Society / Report

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·