News and Information Disorder in the 2020 Presidential Election

Throughout the 2020 election campaign, there were increasing concerns about the spread of false information on social media, as well as discussions regarding the role of platforms in resolving information disorder (i.e., misinformation, dis-information and malinformation). Now that the election is over, we must evaluate the effectiveness of diverse strategies that platforms or media organizations have used, along with the associated ethical and legal ramifications, to address misinformation and disinformation during the election. The Information Society Project at Yale Law School invited leading scholars on misinformation from different disciplines— including communication, computer science, law, psychology and political science—to write about their reflections on important questions that were raised during the presidential campaign and the 2020 Election, particularly related to information disorder created and aggravated by algorithms on social media. You can find the essays below. The essays appear in the order in which they were presented at the Yale ISP conference this fall. Click here to watch the speaker presentations.

Misinformation research, four years later

Towards a diachronic understanding of the harm potential of information disorder — reflections on Election 2020

News organizations as fact-checkers: Any potential issue?

Social influence campaigns in the cyber information environment

Good-enough interventions

Facebook’s responsibility

Coordination: A prerequisite for an effective fight against misinformation

The road to hell is paved with good algorithms: The case for deactivating recommendation algorithms in the political sphere

Experimental evaluation of misinformation interventions

A model for intuitive internet governance

What can and should platforms be responsible for?

The evolution of computational propaganda: Bots, influencers and platform responsibility

Disinformation gets physical: The internet of things as an emerging terrain

Regulating AI: The question now is no longer whether, but how

The 2020 election integrity partnership

The emerging science of content labeling: “Soft” interventions and hard public problems

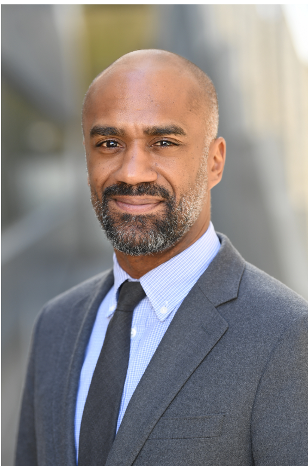

Race, misinformation, and voter depression

Don’t über-blame the algorithms — lessons from Europe

Disinformation and the disingenuous discourse of victimhood

Photo (top) by Johnson Wang on Unsplash