The Future of the First Amendment, 2004 Edition

The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation’s High School Initiative seeks to encourage students to use the news media, including student journalism, and to better understand and appreciate the First Amendment. As part of the initiative, the foundation funded this “Future of the First Amendment’’ research project, focusing on the knowledge and attitudes of high school students, teachers and administrators. Specifically, the study seeks to determine whether relationships exist – and, if so, the nature of those relationships – between what teachers and administrators think, and what students do in their classrooms and with news media, and what they know about the First Amendment. Ultimately, the project surveyed more than 100,000 high school students, nearly 8,000 teachers and more than 500 administrators and principals at 544 high schools across the United States.

High school students’ attitudes about the First Amendment are important because each generation of citizens helps define what freedom means in our society. The words of the First Amendment – Congress shall make

no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress

of grievances – do not change, but how we interpret them does. In recent years, in fact, annual surveys of adult Americans conducted by The Freedom Forum show that public support for the First Amendment is neither universal nor stable: it rises and falls during times of national crisis. In the wake of the 2001 terrorist attacks, the nation was almost evenly split on the question of whether or not the First Amendment “goes too far in the rights it guarantees.’’ Not until 2004 did America’s support for the First Amendment return to pre 9-11 levels, when it received support from only about two-thirds of the population. Even in the best of times, 30 percent of Americans feel that the First Amendment, the centuries-old cornerstone of our Bill of Rights, “goes too far.’’

How will America’s high school students affect this balance? “The Future of the First Amendment’’ findings are not encouraging. It appears, in fact, that our nation’s high schools are failing their students when it comes to instilling in them appreciation for the First Amendment. This study, the most comprehensive of its kind, shows that nearly three of every four students do not think about the First Amendment or say they take its rights for granted.

The study suggests that First Amendment values can be taught – that the more students are exposed to news media and to the First Amendment, the greater their understanding of the rights of American citizens. But it also shows that basics about the First Amendment are not being taught, that 75 percent of the students surveyed think flag burning is illegal, that nearly 50 percent believe the government can censor the Internet, and that many students do not think newspapers should publish freely.

Administrators say student learning about the First Amendment is a priority, but not a high priority. Below are the key findings.

- High school students tend to express little appreciation for the First Amendment. Nearly three- fourths say either they don’t know how they feel about it or take it for granted.

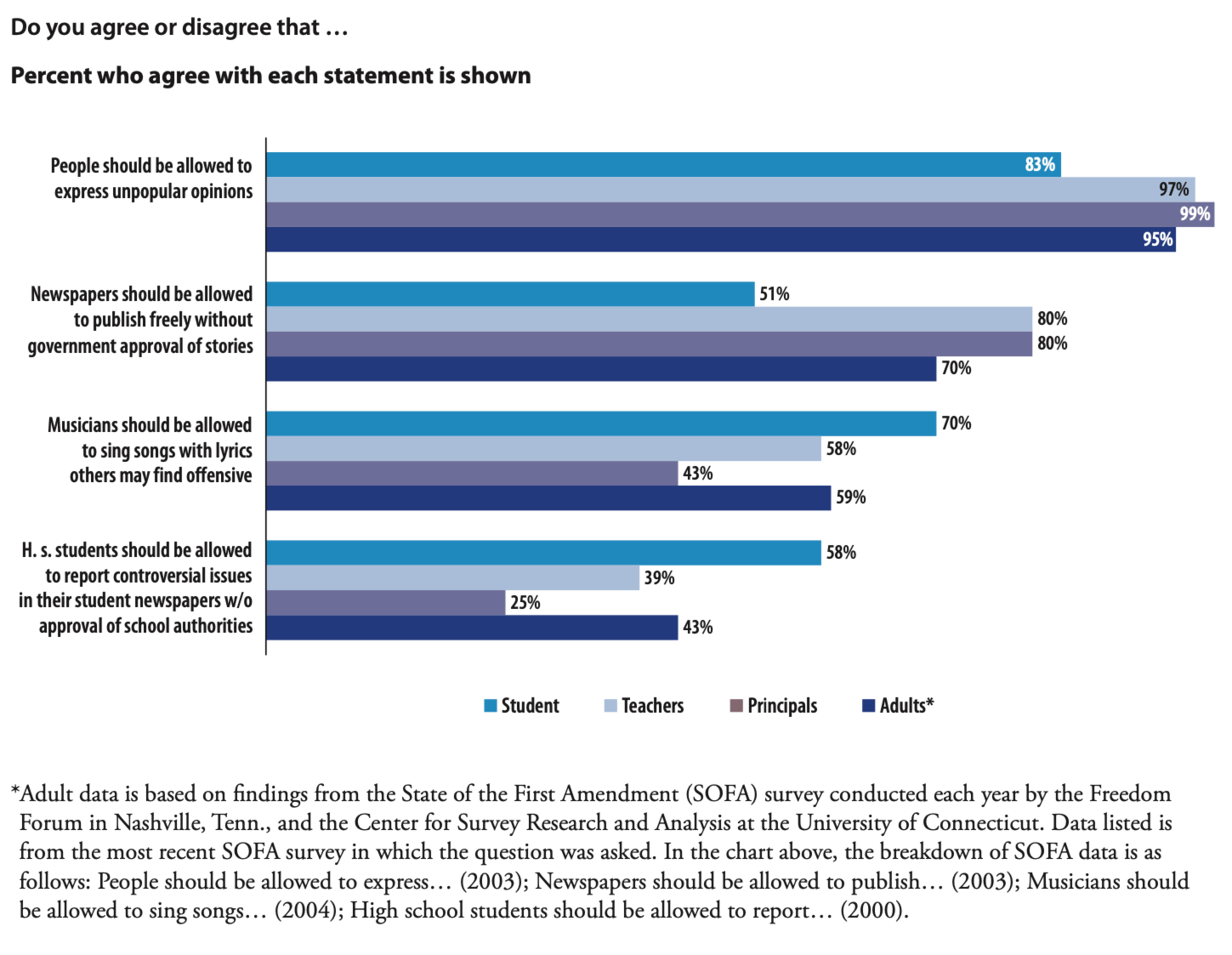

- Students are less likely than adults to think that people should be allowed to express unpopular opinions or newspapers should be allowed to publish freely without government approval of stories.

- Students lack knowledge and understanding about key aspects of the First Amendment. Seventy-five percent incorrectly think that flag burning is illegal. Nearly half erroneously believe the government can restrict indecent material on the Internet.

- Students who do not participate in any media-related activities are less likely to think that people should be allowed to burn or deface the American flag. Students who have taken more media and/or First Amendment classes are more likely to agree that people should be allowed to express unpopular opinions.

- Students who take more media and/or First Amendment classes are more willing to answer questions about their tolerance of the First Amendment. Those who have not taken the classes say they “don’t know” to First Amendment questions at a much higher rate.

- Most administrators say student learning about journalism is a priority for their school, but less than 1 in 5 think it is a high priority, and just under a third say it is not a priority at all. Most, however, feel it is important for all students to learn some journalism skills.

- Most administrators say they would like to see their school expand existing student media, but lack of financial resources is the main obstacle.

- Students participating in student-run newspapers are more likely to believe that students should be allowed to report controversial issues without approval of school authorities than students who do not participate in student newspapers.

- Student media opportunities are not universally offered in schools across the country. In fact, more than 1 in 5 schools (21 percent) offer no student media whatsoever.

- Of the high schools that do not offer student newspapers, 40 percent have eliminated student papers within the past five years. Of those, 68 percent now have no media.

- Low-income and non-suburban schools have a harder time maintaining student media programs than wealthier and suburban schools.

- Interestingly, virtually the same percentage of students participate in media activities in schools that offer a high volume of student media, as in those schools with no media programs. Apparently, students interested in journalism find a way to participate in informal media activities, even if their school does not offer formal opportunities.

Each of these key findings is explored in some detail in the section that follows, with supporting comments from scholastic journalism and First Amendment experts.

For more information about this project, go to firstamendmentfuture.org.

- High school students tend to express little appreciation for the First Amendment. Nearly three-fourths (73 percent) either say they don’t know how they feel about the First Amendment, or they take it for granted.

Schools don’t do enough to teach the First Amendment. Students often don’t know the rights it protects. This all comes at a time when there is decreasing passion for much of anything. And, you have to be passionate about the First Amendment.”

Linda Puntney

Executive Director, Journalism Education Association

After the text of the First Amendment was read to students, more than a third of them (35 percent) thought that the First Amendment goes too far in the rights it guarantees. Nearly a quarter (21 percent) did not know enough about the First Amendment to even give an opinion. Of those who did express an opinion, an even higher percentage (44 percent) agreed that the First Amendment goes too far in the rights it guarantees.

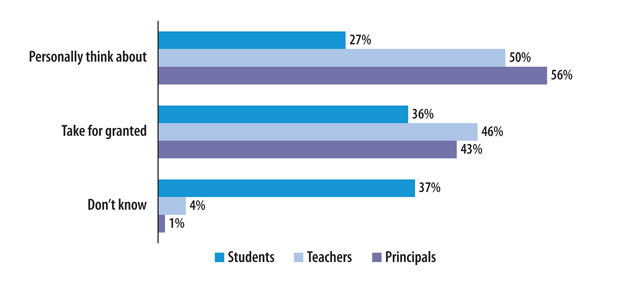

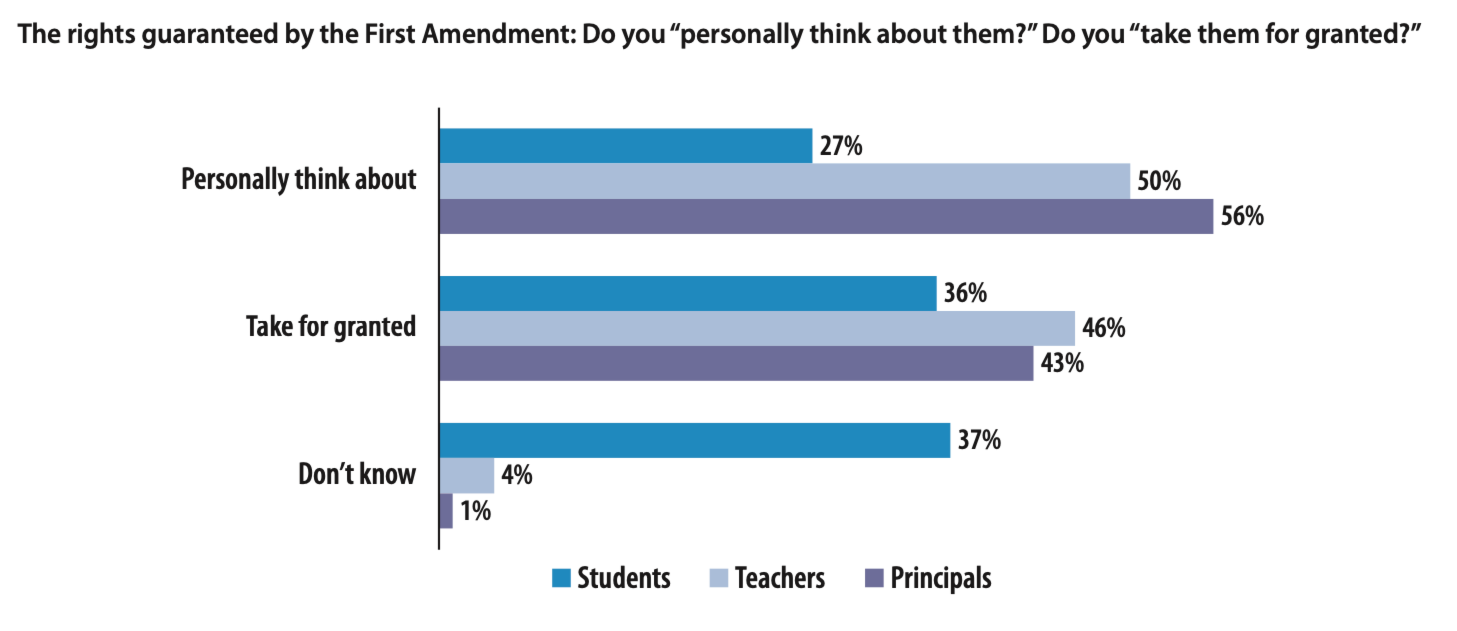

The graphic shows that teachers and principals are more likely to personally think about their First Amendment rights rather than take them for granted, but just 27 percent of students personally think about them. Thirty- seven percent of students either have not yet formed an opinion or are unwilling to express their opinion.

2. Students are less likely than adults to think that people should be allowed to express unpopular opinions or newspapers should be allowed to publish freely without government approval of stories.

“The First Amendment is the cornerstone of our democratic society. Unfortunately, young people don’t live it enough. It becomes like the granite monument in the park that we never visit.”

Sandy Woodcock, Director

Newspaper Association of America Foundation

Adults, teachers and principals are more apt to agree with the traditional forms of expressing one’s First Amendment rights. For example, up to 80 percent think newspapers should be allowed to publish freely without government approval of stories.

The graphic, however, shows that when it comes to situations more relevant to students’ own concerns, students agree at higher rates than adults that certain forms of expression should be allowed (i.e., musicians singing songs with lyrics some may find offensive, and students reporting controversial issues in their papers without approval from school authorities).