Executive Summary

Citizens and journalists rely on access to government information to hold public officials accountable – critical for a strong press and functioning democracy. Yet, all indicators point to increased secrecy in government and a need for more effective acquisition and dissemination of civic data through better laws, technology, litigation, advocacy and public awareness. The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation has invested through the years in countless nonprofit organizations to improve the civic data universe, urging journalism organizations to look beyond their own traditional networks to forge new relationships with their communities and potential partners, expanding the diversity, scope and distribution of news.1

This report represents the second and final installment in a study commissioned by the Knight Foundation to identify barriers for journalists and citizens in accessing government information, and to seek potential solutions. In March 2017, Knight released “Forecasting Freedom of Information: Why it faces problems – and how experts say they could be solved,” where hundreds of journalists, experts and others identified problems and potential solutions. The report found numerous barriers to citizen access to government information, and the prediction that transparency would continue to worsen under the Trump administration, which was affirmed by analyses of federal FOIA performance.2 The report also noted a fractured and scattered access community, many yearning for more collaboration and connectivity to avoid needless duplication and to strategically fill voids, to pool their talents and resources for increased impact.

In the first phase, the study identified the problems confronting freedom of information in the United States. This phase closely examines the organizational landscape and how to improve it for elevating access to government information to the next level.

KEY FINDINGS INCLUDE:

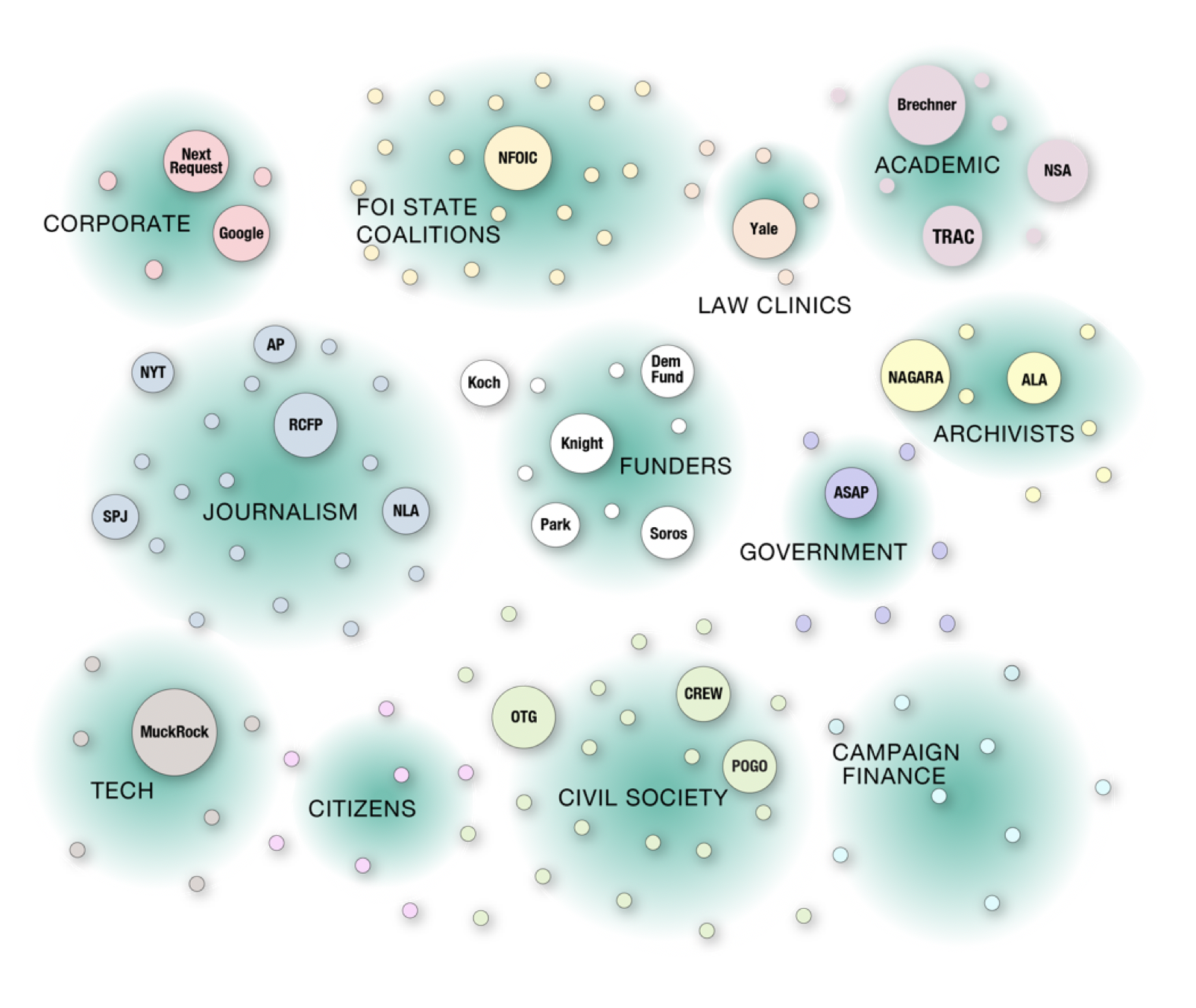

- EXPANDING UNIVERSE: Hundreds of organizations in the United States have an interest in access to government information, clustered in a dozen “galaxies,” such as journalism, civil society and technology. While many journalism groups continue to carry the banner for freedom of information, more and more interests outside of journalism are getting in the game.

- TRUMP BUMP: On average, organization revenues increased 39% from 2015 to 2018, doubling since 2011. Growth varied widely by field and many groups are bracing for a declining economy that could constrain resources in the near future, as well as a diminished sense of urgency if President Trump is not re-elected in 2020.

- PERMANENT FUNDING POTENTIAL: Combined, more than $100 million is spent by these groups each year toward efforts to improve public access to civic data. A $2 billion endowment would guarantee such activities in perpetuity, protecting democracy for generations to come.

- STATE/LOCAL LEVEL SUFFERS: While many groups litigate for federal government information, fewer resources are dedicated to civic data at the state and local level. State press associations and broadcast associations, once powerhouses in monitoring state legislation, have been hurt by declining membership and a focus on protecting member business interests. While many groups focus on federal FOIA litigation, particularly lawsuits that could set strong precedent, fewer resources are available at the local level for day-to-day lawsuits for public records, and the bulk of news organizations are less inclined to sue than they did 30 years ago.

- FUNDING TENSION: Funding must expand beyond the foundations that have provided most of the resources for decades. One option is to tap the commercial world. About two-thirds of FOIA requests are submitted by business interests yet few companies invest in civic data initiatives. For-profit firms benefit from the sweat of nonprofits.

- INCREASING PUBLIC SUPPORT: Not enough has been done to galvanize public support for open information. Some groups have started to research citizen attitudes and how they might be influenced. Now that needs to turn into action, including school curriculum efforts and public awareness campaigns.

- COLLABORATION: Many of the “galaxies” benefit from well-organized groups that serve as coordinating hubs, and while some clusters collaborate, for the most part the galaxies operate independently. There is a desperate need for a “switchboard” to help the hundreds of U.S. organizations communicate and collaborate, building on the lessons learned from the Open Gov Hub as well as global coalitions for open government.

ABOUT THIS REPORT

This study is based on data and insights collected from more than 300 organizations that have an interest in access to government information in the United States (see list online). Most of those are nonprofit groups, spanning a variety of fields including journalism, civil society, technology, libraries and state coalitions for open government. The researcher then analyzed IRS 990 forms, websites and structural factors of the groups, and interviewed 53 of the groups’ executive directors. This study does not claim to have covered all groups and interests in the nation, but it attempts to examine a broad cross-section. Not all executive directors were completely forthcoming with information, and given the diversity of subfields and missions, quantifying “impact” is challenging, requiring some interpretation and qualitative generalization. Ultimately, themes and commonalities emerge from the interviews and data, resulting in conclusions that, with some caveats, shed light on the freedom of information landscape to serve practitioners, funders and advocates.

FINDINGS ARE ORGANIZED IN THREE MAIN SECTIONS:

- Mapping the Civic Data Universe

- Best Practices

- Building Interstellar Connections

I. MAPPING THE CIVIC DATA UNIVERSE

The civic data universe is vast and expanding, comprising swirling galaxies with their own interconnected planets, each planet representing an organization or entity that has an interest in civic data, open data or freedom of information. While many different types of organizations and people could have a connection with civic data, this study identified 12 established and emerging galaxy clusters:

- Journalism: More than 60 nonprofit organizations, and even more state press association and broadcast associations, serve journalists and public records access. About a dozen of the larger groups dedicate a significant portion of their efforts to freedom of information, given its traditional importance in newsgathering.

- Civil society: Hundreds of nonprofit organizations in the United States have an interest in gathering government records to help their cause. Open The Government, for example, helps coordinate civic data issues for about 120 nonprofits working in immigration, government oversight, partisan causes, social justice and other areas.

- Campaign finance: These nonprofits are part of the civil society world, yet are in a galaxy unto themselves given the longevity and impact they have had on freedom of information, such as Common Cause’s efforts in the 1970s to establish campaign disclosure laws and public record laws in the states.

- State FOI coalitions: About three-quarters of the states have nonprofit coalitions for open government, coordinated by the National Freedom of Information Coalition, one of the broadest FOI networks in the United States at the local level.

- University centers: Academic-oriented organizations tend to focus on research and archival collections, such as Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University, the National Security Archive at George Washington University, and the Brechner Center for Freedom of Information at the University of Florida.

- Law clinics: About two dozen First Amendment legal clinics have emerged at law schools throughout the country, spawned in large part by the success of the Media Freedom and Information Access Clinic at Yale and assisted by the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press’ quickly expanding Free Expression Legal Network, aided in large part by generous startup funding from The Stanton Foundation.

- Government: Some organizations have been created by governments to assist in the public records and open data process, such as the federal agency 18F, the Connecticut Freedom of Information Commission and the dozens of public record ombudsman offices established by about half the states. Some nonprofits serve record custodians, such as the American Society of Access Professionals.

- Archivists: Librarians and archivists have a long history and interest in collecting and disseminating government information. The American Library Association, for example, employs a staff member to advocate for the public’s right to know.

- Citizen archivists: The internet empowered dedicated information seekers to create their own website repositories for public records, on their own time. For example, since 2003, book author Russ Kick of Tucson, Arizona, has collected government records and posted them on his website Altgov 2 (previously Memory Hole) for citizens and journalists to use.

- Commercial enterprises: Some companies, such as NextRequest, play an important role in civic data, providing platforms for governments to better manage and disseminate their records and data.

- Technology: From citizen programmers to the richest corporations in the world, the technology sector offers new opportunities and funding sources for civic data. Craig Newmark, founder of Craigslist, for example, has provided millions of dollars through his foundation to support journalism and civic data, as have organizations created by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar. Innovative tools melded with traditional FOI principles offer new ways for people to acquire and make sense of government data.

- Funders: Stalwarts, such as the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and Democracy Fund, have carried the ball for freedom of information, and new players will be needed to join the game. Foundations subtly shape the landscape based on their priorities, and a finite pot of money requires groups to look beyond their galaxies to new sources.

Some planets serve as a hub or center of communication and activity within their respective galaxies, such as the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press within the journalism cluster, or Open The Government within the civil society galaxy. A planet can also serve as a connector between galaxies, such as Reporters Committee connecting First Amendment law clinics at universities with nonprofit online news organizations. But for the most part, the galaxies tend to stay to themselves, focused on their own particular challenges, cultures, social networks and communication channels. This study identified more about 300 organizations that have an interest in civic information, and no doubt hundreds more exist. Some groups, such as MuckRock, are 100% dedicated to civic data. For many others, like the American Civil Liberties Union, freedom of information is a part of the mission. Some planets are large and influential, with many connections and substantial budgets, while others struggle to support basic life. Nearly all groups compete, to some extent, for finite resources.

A key goal of this study is to show how these planets and galaxies connect, where they duplicate, where there are voids, and how they might work together more effectively across galaxies to maximize existing resources and find new resources. Ultimately, it is the hope that these findings will help those interested in civic data find new partners and funding sources, as well as introduce funders to new partnerships and projects that could make long-term, sustainable progress toward a more transparent government, robust information ecosystem and empowered citizenry.

NEW WORLDS, NEW NAMES

As the universe evolves, so does its terminology and different galaxies tend to use different words. The traditional term “freedom of information,” or “FOI,” which gained popularity in the 1960s, is still a preferred term in some of the more established galaxies, such as journalism. The term generally means the legal act of acquiring government records from agencies, typically involving formal public records request letters followed by bureaucratic resistance. Internationally, nonprofit groups refer to this as “Right to Information,” or “RTI.”

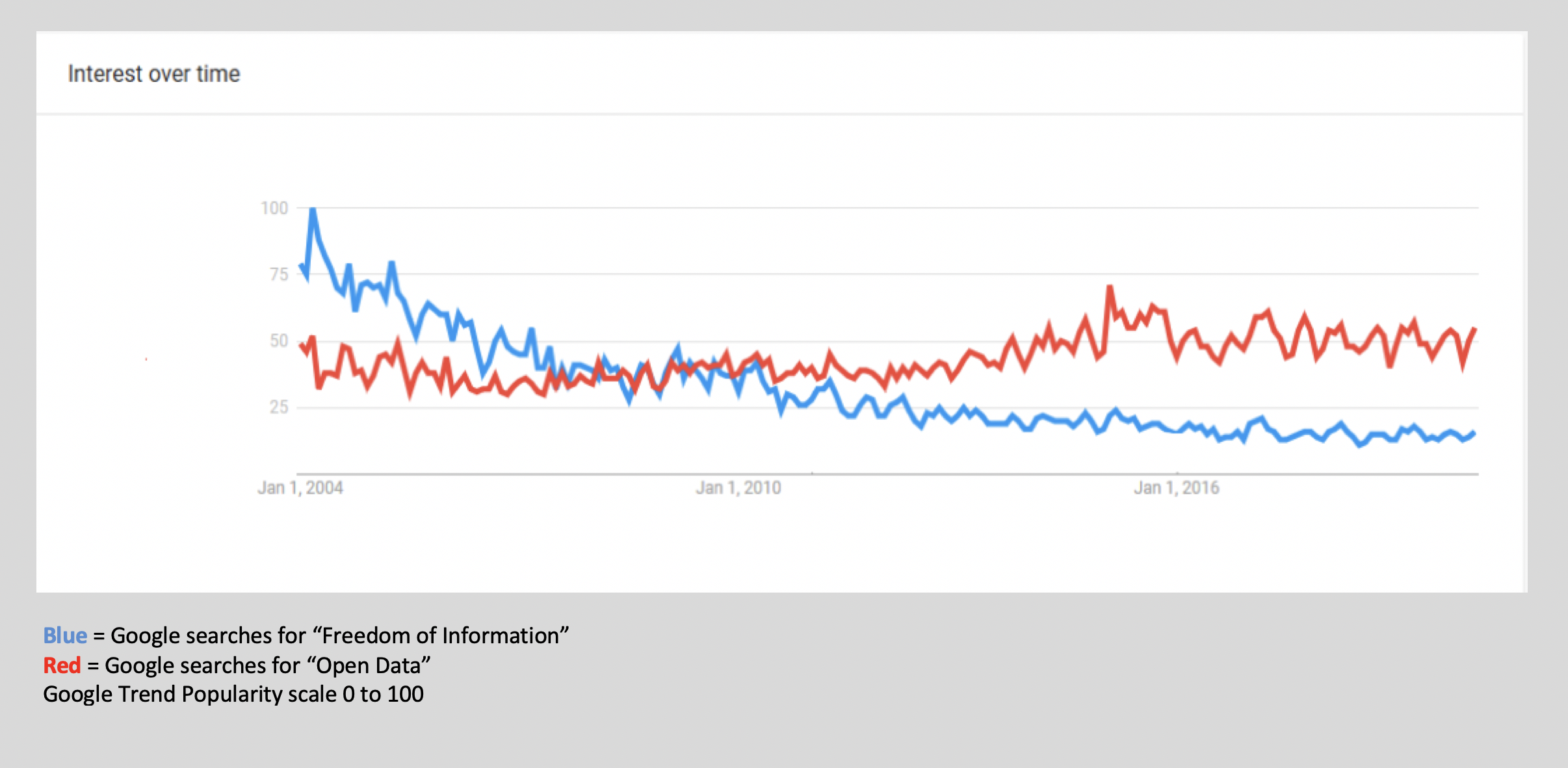

But galaxies formed in the past decade are creating new terms and concepts, most notably “Open Data,” referring to the proactive release of government data online. Google search trends show a significant growing interest in “open data,” and a declining interest in the term “freedom of information,” with open data overtaking freedom of information in 2010. Other terms, such as Civic Data, Open Society, Government Transparency and Right to Information, are used in select groups but have not been widely adopted by the public, at least not yet.

GOOGLE SEARCH TERMS 2004-2020: ‘FREEDOM OF INFORMATION’ VS. ‘OPEN DATA’

The terms “FOI” and “Open Data” are not synonymous, but both share much in common as the two worlds begin to collide. Those in the FOI realm push for proactive release of government data, and those in the open data world see the importance of the legal tools necessary to force government to divulge information. Other terms are emerging, as well, such as “civic data.” Last year, for example, the Brechner Center for Freedom of Information launched a new online Journal of Civic Information to publish research tied to freedom of information and open data.3 For the purposes of this report, “civic data” will be used in addition to FOI and open data. Regardless, the essence of all these galaxies is to foster the sharing of civic information, often government records or data, that help citizens hold government accountable and build a better society.

UNIVERSAL SHIFTS

News organizations once dominated the civic data universe, as the premier collectors and disseminators of civic information, whether it be crime listings, legal notices, city council proceedings, or scandals exposed through government records. After all, it was journalism organizations that commissioned the FOI bible, “The Public’s Right to Know,” in 19534 and led the charge on passage of the Freedom of Information Act in 1966. But as legacy media struggle under a crumbling economic model, and the internet provides new opportunities for information dissemination, new groups and galaxies are emerging to fill the void. Public records litigation by nonprofit groups, for example, have exploded in recent years, particularly after the election of President Donald Trump. In 2001, about one out of every seven federal FOIA lawsuits were filed by nonprofits; By 2018 nonprofits had accounted for more than half, led by Judicial Watch, the American Civil Liberties Union, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, and Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington.5

New leaders from different backgrounds are emerging in the field, particularly from the technology sector. Corinna Zarek, for example, started her career in journalism but moved to law, then worked as the FOI director for the Reporters Committee, then as a staffer at the federal Office of Government and Information Services, moving on as the White House deputy U.S. chief technology officer, and now works for the high-tech nonprofit Mozilla. Computer programmers are melding their skills with open data to create new tools for the public and government, such as Max Galka’s FOIA Mapper, which allows people to electronically search millions of FOIA requests submitted to the federal government. Another bright spot is that about 60 percent of the groups in this study are led by women. However, the leaders still tend to be overwhelmingly white – just 5% self-identify as racial minorities. More work is needed to expand the diversity and backgrounds of civic data leaders.

EMERGING CONNECTIONS

In just the past few years, the buzzword among nonprofit groups in civic data has been “collaboration.” Team efforts, encouraged by foundations, are increasing at a strong pace as groups look to maximize their impact through synergistic partnerships. For example:

- Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press hired a new staff member in fall 2018 to help law clinics learn from each other and better connect with nonprofit news organizations that can use their free assistance. The Reporters Committee also worked with other groups to create FOIA Wiki.

- The National Freedom of Information Coalition moved to the Brechner Center for Freedom of Information at the University of Florida in 2018, where the two organizations share staff, office space and expertise.6

- Open The Government helps about 120 nonprofit organizations, mostly in the civil society realm, coordinate their efforts, and published a 2018 best practices guide to FOIA collaboration.

- The Committee to Protect Journalists partnered in December 2018 with First Look Media’s Press Freedom Defense Fund and other groups to raise funds toward legal defense litigation.

- MuckRock merged with DocumentCloud in June 2018 to build on their combined strengths, and added new apps useful to requesters and journalists, such as oTranscribe and Quackbot.

Coordination is not easy, executive directors say, requiring bandwidth, enthusiasm and a significant level of trust and openness. Major hubs in the galaxies tend to have larger full-time staffs capable of taking on the work required to interact with other groups. In the Open the Government 2018 guide to FOIA collaborations, groups are encouraged to partner with journalists to amplify the impact of their work, partner with litigation centers to help sue for records, create platforms for sharing work, band together on lobbying efforts and work openly to build trust. Interviews with executive directors indicate that is possible and a worthy goal, but easier said than done.

CROWDED LANES

Organizations are becoming more cognizant of who is doing what to avoid duplicating efforts. While some duplication is fine, and even necessary for impact, civic data leaders are becoming savvy at identifying their “lanes.” Here are some of the most crowded lanes:

TRAINING is common to about two-thirds of the groups surveyed, including training of members and citizens. Similarly, many of the groups provide guides and tips about acquiring public information on their websites, and about three-quarters provide reports about freedom of information issues. The most comprehensive websites are hosted by Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, MuckRock, National Freedom of Information Coalition and the National Security Archive. Reporters Committee updated its guides in January 2019 and also created FOIA Wiki. Many state coalitions provide a hotline, and some national organizations provide the same help for anyone to call, including Reporters Committee, News Leaders Association, Society of Professional Journalists and the Student Press Law Center.

REQUESTS are increasingly submitted by organizations to collect records for the public good or for the group’s own niche agenda. Some civil society nonprofits have hired former journalists to produce reports of interest to the groups’ missions, and in doing so end up filing FOIA requests in search of records. This is a growing trend, with about a third of groups now filing their own requests.

LITIGATION for federal government records has been a growing area among dozens of groups. About a third of the organizations surveyed said they sue for public records on their own, typically the same groups active in requesting records. In some cases, a nonprofit might want government records for its particular niche issue, and to show members and funders they are aggressively holding government accountable. As noted earlier, nonprofit groups are suing significantly more at the federal level than they did 15 years ago, and U.S. FOIA litigation is soaring, doubling to nearly 900 lawsuits per year since President Trump was elected in 2016. Some organizations, such as the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, litigate to create substantial improvements to case law. Emergence of law clinics is helping at the local level, but for the most part, current litigation activity is heaviest federally. While BuzzFeedand The New York Times continue to ramp up FOIA litigation, for the most part smaller news outlets are less likely to sue at the local level than in past years. In response, the Reporters Committee launched in 2019 the Local Legal Initiative to place lawyers in the states to help local journalists.

ADVOCACY is noted by about two-thirds of the groups, primarily focusing on public policy work. Often state FOI coalitions help educate legislators about the effect of public record exemptions, and national groups work to improve FOIA or new laws, such as the 2019 OPEN Government Data Act. Three-quarters reported signing onto joint statements or amicus briefs to support open government.

Some organizations are expanding their missions, spreading into other lanes. For example, some organizations that have traditionally focused at the federal level have expanded to cover state/local issues, reflecting a growing interest by funders to help local journalism. Likewise, some groups at the local or state level are working to expand nationally to build on anti-Trump sentiment for fundraising. New partisan groups formed after the 2016 election also have moved into the sphere, such as American Oversight. At the same time, some groups have consolidated or retracted, such as the Sunlight Foundation, or merged with other groups, such as the Center for Effective Government joining the Project on Government Oversight.

BLACK HOLES

While many groups litigate for federal government information, with some exceptions, fewer resources are dedicated to civic data at the state and local level, FOI research and development, technology and proactive lobbying and public advocacy.

STATE/LOCAL LEVEL: Most executive directors said more resources could be focused on access to civic data at the state and local level. State press associations and broadcast associations, once powerhouses in monitoring state legislation, have been hurt by declining member news organizations and a focus on protecting member business interests. “A lot of things are reactionary at the state level, when a legislature proposes bad law,” said the director of a state-level organization. About three-quarters of the states have active coalitions for open government, assisted by the National Freedom of Information Coalition. And of those, just a handful have paid staff. Many rely on volunteers. The Associated Press, a long-time organizer of state FOI audits, has attempted to mobilize its capitol reporters to monitor proposed legislative action through its Sunshine Hub. Yet, while many groups focus on federal FOIA litigation, particularly lawsuits that could set strong precedent, fewer resources are available at the local level for day-to-day lawsuits for public records, and the bulk of news organizations are less inclined to sue today than they did 30 years ago. State FOI coalitions, including the ones with larger budgets, said they still struggle to find basic operational funds and wish for more assistance in fundraising and technology.

STRATEGIC RESEARCH: A handful of organizations provide research about civic data, usually in the form of white papers or reports. Dozens of university scholars in the United States publish peer-reviewed research, but it is rarely seen by those who can use it and often has little connection with practitioners’ day-to-day needs. “I just don’t have time to research the issues,” said one state FOI coalition director. Some university-based organizations are capable of producing useful research, such as the emerging law clinics and the Brechner Center. Also, the National Freedom of Information Coalition is bolstering its research capacity, and launched a new annual FOI research competition in 2019.

TECHNOLOGY: Some groups, particularly state coalitions, expressed an interest in getting help in the use of technology, including website management and creation of online databases or apps to foster transparency in their states. Sunlight Foundation, for example, has worked directly with cities to help them prioritize what records and data should be proactively posted online, after examining FOI logs to see what is in demand. The Reporters Committee hosted 80 journalists and technology experts in 2017 to brainstorm ideas for connecting the technology fields with media, and MuckRock continues to work with technologists to develop new apps. For the most part, however, most executive directors reported a lack of technical staff and tech-savvy board members within their organizations. An effective model for translating technology to nonprofit organizations is the Institute for Nonprofit News’ technical staff to assist emerging nonprofit newsrooms in web development, or the new Newspack Wordpress.com program created by Google, Knight and others to help digital news startups.

PUBLIC EDUCATION: Few groups reported efforts to increase public awareness and support for open government, other than participation in the annual national Sunshine Week each March, the posting of informational materials on websites, and public forums and citizen training hosted by state groups. “There needs to be more public relations in this area,” said one executive director. “It’s a big gap. But who has the resources to do that? What would it look like? All messages wouldn’t please everyone.” Open The Government explored the issue in a 2018 report by surveying citizens to identify key talking points that could increase public support for open government. The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press issued a similar report a few months later assessing public attitudes toward the press and how to change them, following with a campaign in conjunction with the Committee to Protect Journalists.

LOBBYING: A handful of groups directly lobby state legislators and members of Congress on civic data issues. Some state-level groups, such as press associations and state FOI coalitions, educate lawmakers, and Open The Government monitors federal FOIA developments. Few executive directors, particularly those from journalism groups, said they feel comfortable directing their organizations to give campaign contributions to candidates who support government transparency. About 80% of civic data nonprofits are registered as 501(c)(3) organizations, which restricts extensive lobbying. The rest, however, have more flexibility to lobby, as 501(c)(4) or 501(c)(6) organizations.

DIVERSITY: The civic data community, much of it born out of the journalism and legal communities, lacks the gender, racial, age, socio-economic and industry diversity to truly represent the nation’s citizenry and needs. Information is power, and that power should be distributed among all Americans.

RESOURCES

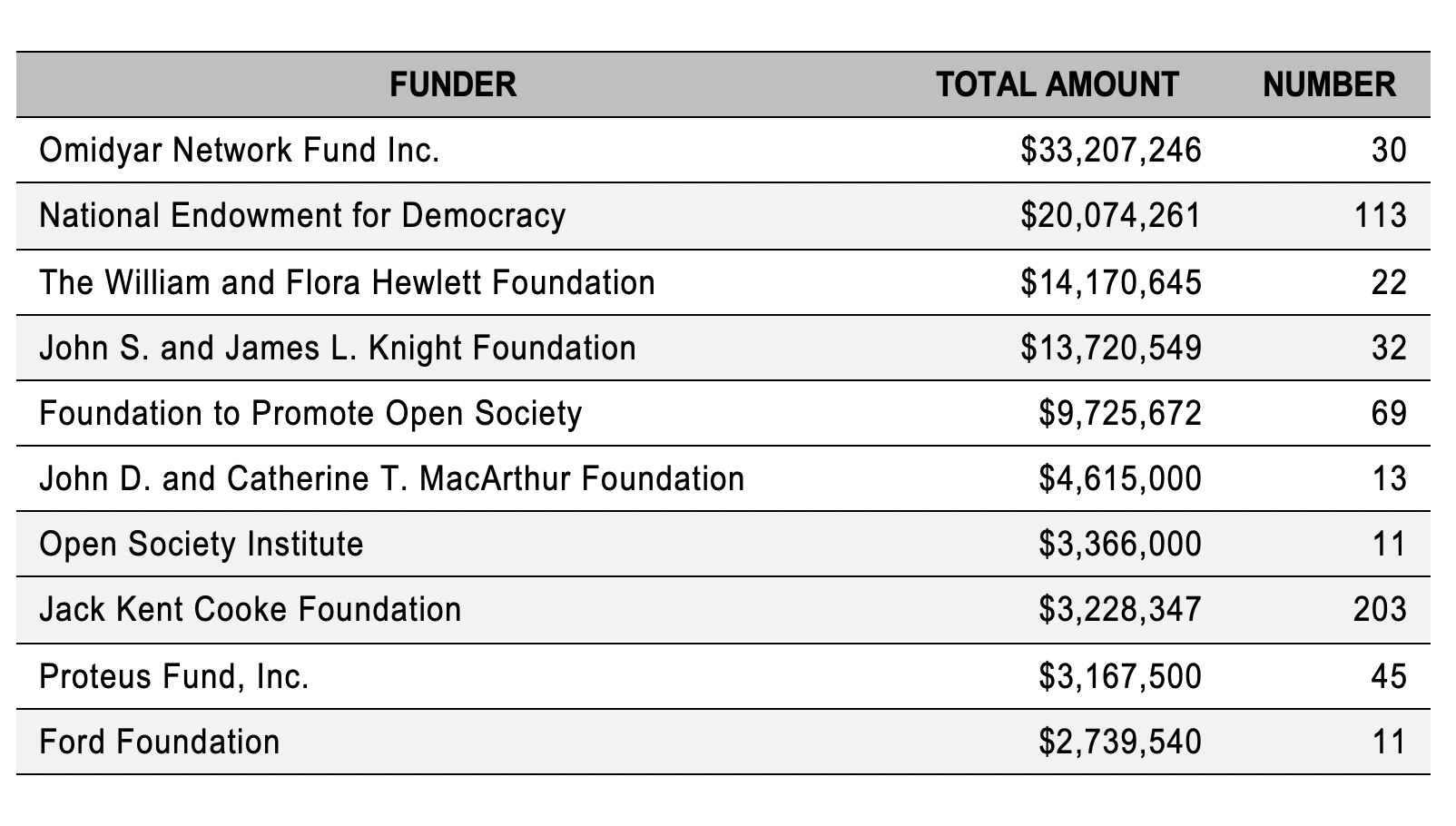

FOUNDATION SUPPORT: In the 53 interviews, the foundations most cited by executive directors as shouldering the civic data burden were dominated by Knight Foundation (19 mentions), Democracy Fund (16), Open Society (3), Robert R. McCormick Foundation (2), MacArthur Foundation (2) and single mentions of Craig Newmark, Jeff Bezos, Lenfest Foundation, Google, the Stanton Foundation and the Charles Koch Institute. According to data collected by Media Impact Funders, about 100 foundations have contributed more than $160 million to 4,499 open government projects in the United States from 2009 to 2020, with the largest contributors coming from the Omidyar Network Fund and the National Endowment for Democracy. Many of the grants were for international non-governmental organizations with offices in the United States – not the typical groups included in this study. Nevertheless, the database provides hundreds of grantors that might be of interest to groups studied in this report.

TOP FUNDERS OF U.S. OPEN GOVERNMENT GRANT RECIPIENTS, 2009 TO 2020

TRUMP BUMP: About three-fourths of the executive directors surveyed, particularly those focused on federal civic data based in Washington, D.C., reported increased donations or members directly related to the election of Donald Trump. One organization raised $150,000 during inauguration weekend alone in 2017. The Committee to Protect Journalists was deluged with donations after a shout-out from Meryl Streep during the Golden Globe Awards in 2017. Large groups with national name recognition, such as the ACLU and Common Cause, saw significant increases in donations and supporters. On the other hand, state-focused groups did not report such gains. Also, some galaxies fare better than others. For example, most librarian and archivist nonprofits saw significant declines in revenues in past years – some as much as 41% since 2015 and total funding in that sector down 4%. Civil society groups, however, saw total revenue increase 39% from 2015 to 2018. Revenues in the journalism galaxy varied widely, with some organizations attracting significant donations and grants, and others foundering. For example, ProPublica, the Committee to Protect Journalists, Freedom of the Press Foundation, Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, Online News Association and Student Press Law Center demonstrated strong revenue gains. Some organizations, including MuckRock, Local Independent Online News Publishers and the National Freedom of Information Coalition, reported significant support the past several years from foundations, particularly the Knight Foundation and Democracy Fund. Also some journalism groups reported new funds from Google and Facebook, although the resources were primarily directed toward improving journalism, not to open government specifically. New donations from the Charles Koch Institute have helped, as well, despite some gnashing of teeth by organizations in accepting the donations. If anything, the support showed that government transparency is a topic that crosses all partisan realms.

FUNDING TENSION: Many executive directors, while grateful for foundation grant support, expressed frustrations at the tension between short-term project-specific grants and general support. “To me, I would say my greatest frustration with the foundation world is that they go from fad to fad and the latest new thing, rather than looking at the core functions of the FOI ecosystem,” said one executive director, who lamented that time focused on fundraising detracted from the mission. “We need to make sure there are vibrant groups funded for general support.” The same person, however, noted the invaluable service foundations provide by acting as a catalyst for change, and their influence by viewing the landscape from 35,000 feet. “They know what everyone is doing. I would get a call from Eric Newton (formerly of the Knight Foundation) every month or two telling me what was going on. That was very helpful.” On the other side, funders say recipients must regularly demonstrate their impact and look beyond relying primarily on foundations for long-term, sustainable revenue streams. It’s not enough to seek funding because FOI is important. Groups must demonstrate measurable impact, clearly-defined activities, and work collaboratively with others to earn support from foundations.

II. BEST PRACTICES

Some groups are faring better than others in the civic data universe, attracting more resources and developing broader connections for more impact. Through the interviews of executive directors and examination of organizational attributes and finances, some commonalities can be seen that appear related to success:

PROFESSIONAL, EXPERIENCED STAFF

Organizations with full-time staff that can focus on communications and fundraising appear the most capable of getting their messages out and attracting resources, allowing executive directors more time to coordinate with other groups. Organizations that rely on volunteers or members tend to be less nimble and strategic. About a third of the groups had no staff for communications, and about half had no fundraising staff. During the past several years, some organizations have been able to add professional staff, greatly increasing their abilities to grow further and achieve more. Some executive directors said they have benefited from hiring employees who telecommute. “You can hire exceptional talent, it lowers your costs, and it’s a national network so we are closer to our participants,” said one.

A key factor for success appears to rest on one person – the executive director. Several groups faltered severely during the past decade when excellent directors were replaced with leaders who created employee churn and credibility crises for their organizations. Conversely, some groups hired new executive directors who brought in significant new grant funding. Larger national organizations attract top leaders, paying $300,000 to $800,000 (the median executive director salary was $155,000, and many are below $100,000). Yet, very few executive directors – about 15% – reported any formal training in fundraising and only 9% had training in organizational management. The median average experience for serving as executive director was just three years; the few who have been at it 20 years or more led some of the more influential organizations.

PRINCIPLE-FOCUSED STRUCTURE

Executive directors focused on appeasing large or dysfunctional boards tended to express struggle, particularly in getting their groups to adapt to changing conditions. Member organizations, particularly those with declining membership, tended to focus a significant amount of resources and attention on member recruitment and retention, providing less focus on civic data issues. Members and boards also tended to pressure executive directors to hoard publicity when collaborating with other groups – a challenge in building trust and stronger networks in the civic data universe. Some groups chose to stick with “supporters” rather than formal members. “Membership creates expectations that we will advocate for them rather than a principle,” said one executive director. Groups with diversified boards appear to do better than those with boards dominated by one sector, such as journalism. A board with more variety brings new ideas, new technology and a broader base for fundraising.

DIGITAL REACH

Many of the organizations expressed a lack of technical expertise on their staff or boards. A third employed no technical staff members. Websites and social media use vary widely. About half the groups had no board members with a strong technology background, and almost all of those that did reported just one or two board members. Groups that focus on technology reported benefits. For example, one organization hired a firm to focus on bolstering supporters, doubling the organization’s supporter list from 75,000 to 150,000 people in three months, using a combination of advertising and Facebook messaging. Innovative groups use technology effectively to provide civic data online or through personal devices. MapLight, for example, provides extensive campaign finance data online for people to search and download, and nonprofit news organizations ProPublica and the Center for Investigative Reporting have led the way in applying technology for effectively disseminating government data.

STRATEGIC LOCATION

About 40% of the organizations have offices in the Washington, D.C., area, which appears to be a distinct advantage when it comes to working with federal FOIA and gaining national attention. For example, many of those in the transparency world attend monthly meetings through the Transparency Roundtable, started by Demand Progress. Some communicate through meetings and a listserv with the informal “No Free Lunch Caucus” on government accountability. The D.C.-based groups tend to be larger and better funded. Some executive directors, however, said it was an advantage when working at the state/local level to be located outside of the Beltway. Some groups enjoy the benefit of a prestigious helpful host, such as a university. The National Security Archive, for example, has consistently requested and posted federal documents since 1985, about 1,500 FOIA requests annually, with the assistance of George Washington University, which provides office space and graduate student assistants.

TRUSTWORTHY LEADERSHIP

The most successful executive directors work well with other groups, building partnerships and bridges. “I think for the most part our community is collaborative,” said one executive director from Washington, D.C. “I think the newcomers are learning that and becoming more collaborative. In this space the funders encourage collaboration. Initially the newcomers are a little more sharp-elbowed. That’s waning now.” Some factors appear to get in the way of collaboration, including:

- HARD WIRING: Natural skepticism and competitiveness among players in this field, particularly in journalism. Good leaders acknowledge this tendency and work around it;

- COMPETITION FOR FINITE FUNDS: Demonstrating success to donors, members and boards to show worthiness for more funding. Partnerships, however, are becoming more valued as funders reward multi-organization proposals;

- COMPETING INTERESTS: Not every organization shares the same mission. Successful leaders look beyond one’s galaxy to open doors to new ideas and new funding;

- TIME: Executive directors are busy running their organizations and fundraising. “I have a gazillion things going on and so does everyone else,” said one executive director.

III. BUILDING INTERSTELLAR CONNECTIONS

Based on the executive director interviews, organizational analysis and the findings from the first 2017 phase of this Knight study, the state of open civic data could be improved in the United States through the following 10 “moon-shot goals”:

1. CITIZEN ARCHIVIST LINK

Tenacious citizen archivists, such as those collecting records for the Government Attic, Public.Resource.org, Government Information Watch and AltGov 2, provide a valuable service to the public, but much of their work goes unnoticed and unused by journalists and citizens. While passionate about civic data, these archivists often lack the skill or time to get information to those who can use it. A coordinating entity in the journalism galaxy could bridge that gap. For example, perhaps a journalism organization could serve as a go-between, connecting records collected by the archivists to reporters on a specific beat. News organizations might even pay a subscription or buy piecemeal databases for first-publication rights to the records, supporting the citizen archivists in their work. MuckRock already does this in some ways by helping active requesters acquire their data and then post it online for all to see, sometimes in partnership with journalists. Similarly, the National Security Archive earns a significant portion of its revenue from libraries that subscribe for the records and publications it gathers through FOIA.

2. SUNCON – NATIONAL FOI CONVENTION

Many executive directors noted the importance of in-person connections for building partnerships and generating ideas. An annual convening where state, local and federal issues can be addressed could include litigators, researchers, practitioners and civic data organization directors. Already some gatherings are hosted for specific galaxies, such as an annual meeting of law clinics at Yale in Connecticut each fall. The National Freedom of Information Coalition hosts an annual summit for its coalitions, and in spring 2019 added FOI researchers to the agenda. National groups meet in the summer during the anniversary of the Freedom of Information Act. The Global Conference on Transparency Research, focusing on research in international access, held its sixth gathering in Brazil in 2019. Many groups discuss civic data at their own conferences. Yet, there is no single conference about freedom of information in the United States, bridging state and local, practitioners and scholars, advocates and government custodians.

3. CIVIC DATA STRATEGIC RESEARCH CENTER

Just as medicine, manufacturing and agriculture require strong research and development for advancing civilization, so do those who protect democracy. Executive directors noted the need for a more systematic structure for producing research that answers key questions and better informs advocates, policy makers and the public. State coalitions and press associations, for example, routinely require quick summaries and comparisons of how all the states handle a particular aspect of public record laws. Access advocates need hard facts – not just compelling anecdotes – to demonstrate the benefits of transparency, particularly when weighed against competing interests, such as privacy invasion or national security. Existing academic centers, such as the National Security Archive and Brechner Center, already provide a framework for developing generalizable research. Some organizations provide strong white papers. A coordinating entity could help bring together the various research, catalogue and organize it, and get it out to those who can use it on the street – a bridge between researchers and practitioners.

4. CIVIC INFORMATION LITERACY CAMPAIGN

Executive directors noted the lack of attention on increasing public support for open civic information. One state coalition director, who fends off secrecy legislation each year, said increasing public support for transparency is critical. “If we are going to make improvements on the legislative front then it isn’t going to come from the journalists anymore,” he said. “It needs to come from the public. Finding ways to educate the public would be helpful.” Several groups have started to research what citizens think and how attitudes might be affected. Now an effort needs to put that into play, including, potentially, public service announcements, school curriculum modules and public awareness campaigns. Many executive directors lamented the declining support of national Sunshine Week, largely driven by the Reporters Committee, Associated Press and News Leaders Association since 2005. Impact metrics have been difficult to assess, yet many executive directors said it has made a difference. Examination of the Google Trend chart reported above indicates spikes in Google searches for “freedom of information” nearly every March since its beginning. “There’s not the coordination it used to have,” said one executive director. “It should have double or triple the resources to engage the public.”

5. SUNSHINE SWITCHBOARD

Create a neutral “switchboard” to help the hundreds of U.S. civic data organizations communicate and collaborate, building on the lessons learned from the Open Gov Hub, as well as global coalitions for open government, such as the Open Government Partnership. The coordinator could not be perceived as industry-specific, such as a journalism organization. Many executive directors said an existing organization could run it, provided it would not be perceived as “in charge.” It would have to be perceived as a “Switzerland.” Perhaps it could have two offices, one in Washington, D.C., to work on federal issues and one in the heartland, say Denver, to focus on state-local issues. It might be possible to have a group like Open The Government coordinate federal efforts, given its connections with D.C. groups and location, while the National Freedom of Information Coalition, headquartered in Florida, or another group could focus on coordinating efforts at the state/local level, both working in tandem. “In a perfect world Open The Government could be the switchboard,” said one executive director. “That would make sense, but collaborations are not just science – it’s an art and personal trust is needed.” Some said a university could constitute neutral territory. Regardless of who would do it, some stressed the importance of getting input and buy-in from the FOI community. Some suggested an in-person physical convening to build trust among the key players. Many suggested that a listserv and website would not be enough to facilitate effective communication – executive directors are too busy to check either. It would require proactivity – someone reaching out to each group routinely, collecting information and then matchmaking with other groups. Trust-building is essential, said one director: “That takes time to build interpersonal relations.” One hub tried doing a newsletter, but it was difficult to get members to share what they were doing, fearing others would poach their ideas. “It’s a dog-eat-dog world in the nonprofit world. It’s enormously frustrating.” The coordinator, whoever it would be, would need credibility, some experience with FOI, and be personable and trustworthy.

6. STATES CIVIC DATA POLICY CENTER

Many group leaders, particularly those at the state level and directors of state FOI coalitions, mentioned a need to centralize efforts for legislative change across the country, similar to the New Voices campaign that the Student Press Law Center has led, prompting 14 legislatures to adopt stronger press freedom protections for student journalists. A coordinating body could identify the key legal provisions that would enhance access and then work to get them adopted in legislatures.

7. STRATEGIC LITIGATION FRONT

More funding has been applied to litigation efforts in the public records sphere in recent years, such as the creation of new law clinics, launching of the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, formation of the First Amendment Forever Fund by the Society of Professional Journalists, additional lawyers put to work by Reporters Committee, court fee assistance by the National Freedom of Information Coalition Knight Litigation Fund, and litigation funded by First Look Media’s Press Freedom Defense Fund. However, thousands of journalists and citizens are routinely denied information they deserve to see and have little recourse, not having prestigious law firms on retainer or litigation support from their news organizations’ owners.7 The combined costs for the nation’s day-to-day access litigation is far too much for any foundation or philanthropist to fund. So rather than attempt to find more money to litigate, create a system that lets the market do the work: mandatory attorney fee-shifting provisions in public record laws for those who prevail in litigation. If attorneys are guaranteed to be paid for successfully litigating a public records case then they will gladly volunteer to take cases on contingency, as they do in Florida, Washington state, and a dozen other states. A center could get strong provisions adopted by legislatures, work with press associations and broadcast associations to pair journalists with lawyers, and train local “mom-and-pop” attorneys throughout the country to successfully litigate access cases for citizens and community journalists who can’t afford to litigate on their own. In addition, the resulting payouts would provide greater incentive for local governments to follow the law. Already some strong networks exist to develop such training and coordination, such as the Media Law Resource Center and the networks of local pro-bono attorneys maintained by the Student Press Law Center and Reporters Committee.

8. SUNSHINE COALITION TRAINING CENTER

Create a training hub for groups in fundraising, effective management and increasing impact, and provide a minimum endowment of $2 million per state (including Washington, D.C.) for base operations support to cover one full-time professional FOI expert per state, ideally more for larger states. Coordinators would seek out further funds at the local level, monitor legislation and report back to the hub for identifying national trends as they emerge. A $100 million investment by a philanthropist or foundation would guarantee endowments for every state in the nation to employ one full-time person looking out for government transparency, forever. Even better, cultivate innovative and diverse new voices to the field through targeted graduate school fellowships at programs strong in civic data. After all, a new generation of leaders will need strong attributes to attract new resources, not by focusing on “need,” but rather their own vision, knowhow, courage and innovation.

9. NEW FUNDING OPPORTUNITIES

The civic data universe must expand its revenue options, going beyond the stalwart foundations that have shouldered the burden for years. The commercial world is a relatively untapped resource. About two-thirds of FOIA requests are submitted by business interests,8 yet few companies invest in civic data nonprofit organizations – benefitting from the sweat of nonprofits for their own financial gain. Commercial information providers, Google, and other companies that benefit from a free flow of information should invest heavily in the civic data universe. “Tech companies have not embraced transparency outside of their company interests,” said one executive director. Some groups, as well, have benefited from a relatively new spotlight from Hollywood. The Committee to Protect Journalists demonstrated the power of a shout-out by Meryl Streep at the Golden Globe Awards in 2017. In January 2019, the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press garnered a $1 million grant from the Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Looking beyond the traditional funders includes accepting funds from groups that might appear partisan but also share a passion for accountable government, such as the Charles Koch Institute. Matching donations from Open Society would demonstrate that FOI is for everyone. At minimum, organizations can look outside their own galaxies through IRS 990 forms to see if funders in other fields would spread the wealth.

10. FEDERATION OF CIVIC DATA FUNDERS

Ultimately, to protect democracy forever, philanthropists and foundations could collectively contribute to a new foundation, or consortium, that would endow freedom of information activities in perpetuity. A $1 billion fund, for example, for infrastructure-building in government transparency, could distribute $50 million annually for endowments and short-term projects. Within two years every state could have an endowed FOI coordinator. Currently, all of the active 38 state FOI coalitions total just $2.5 million in revenues, a miniscule expense when compared to the 2018 budgets of large national organizations, such as the ACLU ($144 million), Judicial Watch ($71 million), ProPublica ($27 million) and the State Policy Network ($17 million). A board representing all the galaxies and interested foundations could help guide expenditures and priorities. Is $1 billion out of question? In 2018, Jeff Bezos gave $2 billion toward a fund to serve the homeless and other causes, and $1 billion is less than 1% of his $135 billion net worth. Likewise, Michael Bloomberg, whose empire relies on the free flow of information, gave $1.8 billion in 2018 to Johns Hopkins University. Google, Facebook, eBay and other information-rich companies could guarantee a healthy information flow without wincing. Just $1 billion. Just $1 billion to revolutionize people’s access to civic data in the United States. A small price to pay for saving democracy and holding government accountable, for generations to come.

CONCLUSION

The United States has reached a pivotal juncture in its history, with democracy teetering in the balance. Organizations tasked with protecting freedom of information are scattered, many working in silos, stretched too thin to look beyond their day-to-day challenges. In the first report of this Knight study, one observer noted that the civic data community is like a pride of feral alley cats: “wet, surly and difficult to herd.” The cynicism and skepticism that make them so good at questioning government also impedes cooperation and trust in working together toward the common good. No longer can this universe of passionate, determined advocates work individually, especially given the formidable forces pushing back against transparency, attempting to shroud the public’s eyes from what its government is up to.

The good news is a lot has changed in the past 30 years. Groups are more willing to cooperate, to pool their resources and build on their strengths for the greater good. This productive force can be contagious, can grow with further trust-building, communication, and successful ventures. The Trump administration has provided a golden opportunity to rally those together who oppose increased secrecy.

This study has identified about 300 organizations committed to the free flow of civic data, roughly clustered into a dozen galaxies. While these different fields and industries might employ different terms, all work toward the dissemination of information to empower citizens and help them better self-govern. As news organizations struggle to adapt to changing revenue models, other organizations are filling the void, particularly in litigating for government information. Dozens of groups provide their members or the public training and informational resources, and they routinely work together to advocate for open government.

More work, however, is needed at the state level, better connections are needed between researchers and practitioners, groups should amplify their impact through technology, and greater emphasis should be put on increasing FOI support among the public and policy makers. This report laid out 10 potential ideas for building innovative collaborations in the civic data universe, to harness the collective wisdom, energy and resources for the common good. But this is just the beginning. More groups will need to be mapped, more ideas generated, more partnerships solidified. This will take trust, time and the commitment of everyone, including funders, philanthropists, journalists, technologists, government and the public.

This can’t be just a lofty goal. It must become reality. The enlightenment of all Americans, and their ability to retain their power to govern, depends on it.

APPENDIX: METHODOLOGY AND DATA

METHODOLOGY

The author identified and catalogued more than 300 organizations that have an interest in freedom of information or open data, entering key information about each group into an Excel spreadsheet, using information provided on group websites and IRS 990 forms. Information included address, director name, year founded, IRS status, revenues and expenses for 2015 through 2018, and other facts. The author then conducted hour-long phone interviews with executive directors of 53 of the organizations from January through December 2018. The 50 questions solicited information about the director, staff composition, board composition, organizational activities in freedom of information, key funders, and open-ended questions about challenges, needs and potential solutions for greater collaborations with other groups. Directors were told that their information and quotations would not be attributed to them to encourage honesty and openness in their answers. Interviews were transcribed and analyzed for noteworthy themes and commonalities.

THE RESEARCH TEAM

David Cuillier, Ph.D., is an associate professor at the University of Arizona School of Journalism, where he teaches data journalism and access to public records, and also served as school director 2012-18. He was a newspaper reporter and editor in the Pacific Northwest before earning his doctorate from Washington State University in 2006. He has served as Freedom of Information Committee chair and national president for the Society of Professional Journalists, was elected board president in April 2019 of the National Freedom of Information Coalition, and is editor of the Journal of Civic Information. He has testified before Congress three times regarding FOIA, writes an FOI column for the Investigative Reporters and Editors journal, and is co-author with Charles Davis of “The Art of Access: Strategies for Acquiring Public Records” and “Transparency 2.0: Digital Data and Privacy in a Wired World.”

Eric Newton, innovation chief at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University and former journalism vice president at the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, served as the study’s consulting editor.

THE DATA

To see the list of the more than 300 groups examined in this study, including funding organizations, visit our online directory. For additions or updates to the list, contact David Cuillier at [email protected].

ENDNOTES

- Michele McLellan, “Journalism and Media Grantmaking: Five Things You Need to Know, Five Ways to Get Started,” Media Impact Funders, 2018, https://mediaimpactfunders.org/5-things/

- See for example, Ted Bridis, “US Sets New Record for Censoring, Withholding Gov’t Files,” The Associated Press, March 12, 2018, https://www.apnews.com/714791d91d7944e49a284a51fab65b85; and Ben Wasike, “FOI in transition: A comparative analysis of the Freedom of Information Act performance between the Obama and Trump administrations,” Government Information Quarterly, December 14, 2019, https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0740624X19303788?token=ABEE5CF2337BC142E941D75F901C8CE80D76C519318B66FDF8C2D8257F9F30D7FA56D0376E65784F3B4F050D90F0EC0D

- In full disclosure, the author of this study serves as editor of the journal. The journal was created by Frank LoMonte, director of the Brechner Center at the University of Florida’s College of Journalism and Communications.

- Harold L. Cross, “The Public’s Right to Know,” 1953, Columbia University Press: Morningside Heights, NY.

- See “FOIA Suits Filed by Nonprofit/Advocacy Groups Have Doubled Under Trump,” October 18, 2018, by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse FOIA Project, http://foiaproject.org/2018/10/18/nonprofit-advocacy-groups-foia-suits-double-under-trump/

- In full disclosure, the author of this study was elected president of NFOIC on April 11, 2019, as this project reached its final stages.

- “News Organizations’ Ability to Champion First Amendment Rights is Slipping, Survey of Leading Editors Finds,” Knight Foundation, April 21, 2016, https://knightfoundation.org/press/releases/news-organizations-ability-champion-first-amendmen

- For example, see Margaret B. Kwoka, “FOIA, Inc.,” Duke Law Journal, 65(7), 2016.