Analysis by Joan McQueeney Mitric and Djordje Padejski

BELGRADE — A massive excavation of secret graves and long-shrouded historic military files is under way in Serbia. In a potentially transformative convergence of political will and cutting-edge digital tools, this fledgling democracy may finally get the knowledge it needs to confront and freely debate its hidden and often horrific past.

Consider:

-

A special commission on secret graves set up in 2010 to find and document those killed by Josip Broz Tito’s reviled secret military police has unearthed 190 mass graves at 23 sites across Serbia to date. In January it reported that at least 22,000 people were executed, most without trials in the brutal post World War II years.

-

Special prosecutors for 1990s war crimes have opened 35 criminal cases since July 2003, all stemming from the bloody, fratricidal wars of secession that ripped the former Yugoslavia asunder between 1991 and 1999. To date, 61 people stand convicted. Many more await trial.

-

Balkan scholars and Serbian historians are beginning to revise academic works and textbooks based on recently opened and publicized archival materials.

-

Ordinary Serbs are seeking the truth behind stories their grandfathers once dared whisper only in the night.

This movement toward truth and reconciliation is spurred partly by Serbia’s aspirations to join the European Union, and more concretely by the new, searchable, state-of-the- art Serbian Military Archive at the Zarkovo base 40 minutes from Belgrade. Eventually, this archive will preserve some 40 million pages of previously guarded military records that until 2006 lay moldering in basements and scattered in complete disarray across a city still rebuilding from NATO’s 1999 bombing.

The brainchild of the Jefferson Institute — which takes its mission statement from Thomas Jefferson’s challenge “to pursue truth, wherever it may lead” — the quest to develop an archive and digital-search tool began in 2006 with an early seed grant of $50,000 from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

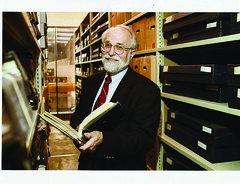

Aaron Presnall, president, Jefferson Institute

Early document preservation and data retrieval done with Knight’s grant was so promising that the government of Norway pledged $900,000 over three years; Canada and the Rockefeller Brothers Fund followed suit, donating $7,000 and $130,000 respectively.

Some four years on, Serbia’s special prosecutors of 1990s war crimes, as well as those investigating Tito-era extra-judicial killings, are using the archive to speed their research. Perhaps most exciting of all, a new open-source archive using many of the database and digital search tools created for Serbia’s military archive — will be replicated in Sarajevo, Bosnia. But with crucial differences: the Bosnian archive will be a civilian-controlled resource library and the software design will be such that it can be replicated and used for free by archives around the globe.

The Bosnian archive project represents a “180-degree turn” from 1993 when Serbian paramilitary forces were shelling Sarajevo’s National Library, destroying Bosnia’s mosques and effectively “trying to wipe out its history. Now Serbia is helping to restore it,” said Aaron Presnall, president of the Jefferson Institute.

So what exactly can Serbia’s military archive do that puts it ahead of the curve compared to many archives around the globe?

For starters, the archive took Serbia’s 40 million military documents, none of which had been digitized, and began to systematically organize and scan them. Starting with the oldest from 1716, and proceeding systematically until today, when almost four million military cables, memos, field maps, letters, discharge papers, battle plans and other records are now in an accessible, searchable form. This historical collection is simultaneously linked to a larger metadata schematic that can be annotated by researchers as they work, Presnall said.

This means instead of spending days weeding through fragile, oversized paper tomes, researchers can now flip through as many as 6,000 digital documents a day, and access a trove of archival military records dating from the Kingdom of Serbia in the 18th century, through both World Wars, the rise and rule of Yugoslavia’s Socialist dictator Josip Broz Tito (1944-1980) and on into the tyrannical, often bloody reign of President Slobodan Milosevic (1989-2000).

All this with a few clicks on the user-friendly interface while sitting at a computer in the archive library at the Zarkovo military base. Most remarkably, many documents are searchable in a way similar to a Google search, using keywords that search the full text of documents.

“We shrunk the time it takes to search and retrieve a document from six months to six seconds,” said Jefferson Institute’s Presnall, who is convinced that the creation of a digitized trove of documents — transparent to all users and easier to contextualize — will prove much more valuable in the long term than a WikiLeaks-style dump.

There’s one big caveat: documents are classified for 50 years. So users who want to see records after 1961 must get special permission from Serbia’s Ministry of Defense (MOD). Many historians, and international and local prosecutors have done just that. Others have found such access tough sledding.

For Sonja Licht, a leading Serbian human rights activist who heads the Belgrade Fund for Political Excellence, “The archive is a marvelous technological tool in the fight for greater transparency.”

“With this new archive, our military history is no longer hidden behind thick walls where we can only guess what’s in the record,” said Licht, a founding member of the Jefferson Institute and whose husband spent two years in jail in the 1980s for his support of student dissidents.

Edward C. Papenfuse, chief archivist for the state of Maryland who has visited the Serbian archive twice, is bullish on the potential global reach of Serbia’s new archive tool. “Really, it has no peer in the holistic archival sense,” he said, noting that this archive outstrips many in the United States, where city and state records remain largely indexed paper collections.

Pleased as he is with the archive’s search and security architecture, Papenfuse, like other open-records advocates and media observers, has lingering concerns about its accessibility to ordinary users, given that it is now housed within a military base and controlled by the staff there. “Ultimately, what is put into the system is going to be controlled, or scrubbed or censored, by the entity doing the scanning. In this case, the military.”

Echoing his concern, Marko Milosevic, a researcher with the Belgrade Center for Security Policy, an NGO committed to greater civilian and military cooperation, said “it is impossible to know what is missing. Today, there is no real oversight about what is, or is not, in the archive.”

Jefferson’s Presnall acknowledges no one knows exactly what records may have been destroyed by political decree, military commanders or merely eroded by time, but he believes “remnants” of original documents remain. The archival collection is simply “too big” to scrub entirely, he said.

For Ph.D. candidate Ljubinka Skodric, the speed and organization of the archive is definitely helping her research into the closeted history of Yugoslavia’s Fascist movement in the late 1930s. But, Skodric says, the archive’s location 90 minutes by bus from Belgrade’s center city is an automatic “chilling factor” to would-be users. Requests to the Ministry of Defense to use the archives can take several days to a month, Skodric said.

Acknowledging these concerns, Papenfuse hopes “soon enough, there will be pressure on the Ministry of Defense to open the archives, “perhaps by linking them to places outside the Zarkovo facility. But for now, we have to live with the political realities of the country we’re dealing with,” he said.

A thawing in the MOD mind-set may already be afoot. In a recent interview Tanja Miscevic, state secretary of Serbia’s Ministry of Defense said, “MOD is seriously considering making more military records available on its official website or over the Internet.”

She noted that the archive has attracted numerous military investigators and historians from Germany, Hungary, Bosnia and Norway who are using the archive to gain clarity about their own roles in 20th century Balkan history, and to bring people guilty of war crimes to justice. Hungarian, Sandor Kepiro, 96, was arrested in December 2010. He is charged with crimes allegedly committed during a 1942 raid by Hungarian Nazi sympathizers on the northern Serbian city of Novi Sad that left more than 1,200 civilians dead.

Secrets from the Grave

Some of the most riveting findings starting to trickle out from the archive’s files are the personal stories of ordinary users who are finally learning the secrets their parents and grandparents took to the grave.

When Dusan Vasovic, 75, visited the archives in 2010, he had no idea what he’d find out about his father. When his father died in 1973, his past was buried with him. “I was shocked when I saw my father’s name as one of the main figures in a coup” that changed the course of WWII history, Vasovic said.

In Zarkovo’s files he learned his father, an army major in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia’s forces, was one of the senior officers who refused to go along with a secret pact signed with Hitler’s Germany in March 1941. He and his band of like-minded soldiers took over the offices of the army and navy in Belgrade and supported the coup that brought Serbia firmly into the Allied camp.

“Better graves than slaves,” demonstrators shouted as Vasovic’s father led a group of soldiers from a park to the ministry on Kneza Miloša street. The crowd sang patriotic songs and shouted slogans against Hitler and Mussolini. Vasovic learned for the first time that his father was arrested, jailed for four months and then placed under “house arrest” by German occupation forces, where he lived in fear of being sent off to a labor camp. Vasovic located this information in a secret report (sent to German envoy Victor von Herren in Belgrade) among the Nazi records now part of Serbia’s archive.

Immediately after the war, anyone who wasn’t a card-carrying Communist was hunted down, locked up or killed by Tito’s forces as he consolidated power. Based on what he learned about his father’s past — Vasovic is convinced his father decided that the only way to protect his family was to renounce any prewar beliefs, stop going to church “and to live out his life as a good Communist.”

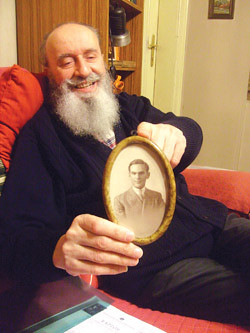

Dobrivoje Tomic, top, examines a cross marking the mass grave site in eastern Serbia where his father may be buried. The pre-WWII portrait above shows Tomic with his father Dusan. In 1944, Dusan Tomic was “disappeared” by Tito’s reviled secret police. His son, now 80, is looking for his grave with the help of Serbia’s Secret Graves Commission.

There were no dramatic bedside revelations when Vasovic’s father died in 1973. Not only did his stories about his role in the opening days of WWII go with him to the grave, but his sons and grandson never knew that the family patriarch they were burying was a fluent French speaker, who had studied at an elite explosives school in Paris from 1928 to 1930.

Hopes for Justice and Comfort

To revisit post-WWII Yugoslavia is to find a place where oxcarts piled high with bodies of anti-Communist sympathizers rolled through village streets and bludgeoned corpses floated in the Danube. People were executed and buried in still-undiscovered mass graves and families had loved ones ripped from home at night never to be seen again. Many living in Serbia today still have no idea what happened to their relatives: where or how they were killed, by whom and where they might be buried.

Today, two different entities are charged with trying to unravel these mysteries: The State Commission for Mass Graves of Those Killed Since September 1944 and the Special Prosecutor for 1990s War Crimes. These investigations into two distinctly horrific and politically repressive eras are giving the archives a meaningful historical role – and hopefully will provide some measure of justice and comfort to descendants of the dead.

Dobrivoje Tomic, 80, a retired dentist, was 13, when the secret police dragged his father from their house one dark night in 1944. Tomic said his father, Dusan, was “neither a soldier nor a politician.” His apparent crime? He was a successful businessman who owned oil and tin factories and a printing press in eastern Serbia.

Tomic said that after 59 days in jail, his father “disappeared.” The Communists confiscated the home he shared with his mother, Radmila, and she was sentenced to death. Somehow, mother and son escaped to Belgrade and then to Austria and Germany, where Tomic studied and worked until he finally felt safe to return home and to search for his father’s grave. In 2010, Dobrivoje Tomic told his story to the Secret Graves Commission.

His account, along with records in the military archive, will be used to try to learn his father’s fate. Tragically, investigators last year unearthed dozens of skeletons in a mass grave near the Tomic family home. When the ground thaws this spring, exhumations will begin again, and Tomic hopes to find his father’s remains among them, if only to finally close a sad chapter.

Workers cover a suspected mass grave in Boljevac, eastern Serbia with a large stone as Dobrivoje Tomic, watches. Tomic is trying to locate the remains of his father, who disappeared in 1944. Bone fragments, in the second photo above, were found at the site by investigators of Serbia’s Secret Graves Commission.

Srdjan Cvetkovic, the historian who heads the Secret Graves Commission, said much of the hidden story behind a “massive and well-organized campaign of terror by Communists” lies in the military archives. The commission wants to locate, mark and, where possible, exhume the long-missing remains. Only then will the country’s dirty linen from 65 years ago, get the airing it needs for Serbia to move closer to a true democracy, he said.

Perhaps most cathartic for citizens of the former Yugoslavia, are investigations under way by the Special Prosecutor for 1990s War Crimes. Prosecutors would not comment for this report because of pending criminal cases, but their indictments directly cite records from the military archives. They make for grisly reading.

-

On Nov. 28, 2007, 14 Serbian paramilitary thugs and soldiers in the Yugoslav National Army were charged with the October 1991 deaths of 70 unarmed noncombatants living in the Croatian village of Lovas. According to the indictment, soldiers killed 21 civilians as they captured the village in a random and sadistic firefight. During the siege, another 27 civilians were physically abused, tortured and killed in an improvised jail. Twenty more civilians were killed while being marched across a minefield.

-

Bosnian Croat commander Ilija Jurisic is appealing his recent conviction for killing 50 unarmed soldiers and civilian truck drivers and wounding 44 more. According to the indictment based on records from the military archives, Jurisic ordered a mortar and rocket-propelled grenade attack on an unarmed Yugoslav National Army column as it withdrew from the city of Tuzla.

Toward an Open Society

So, why is it important that cases like these are vetted in the press or tried in open courts? And what does it have to do with the Knight Foundation’s grant to the Jefferson Institute? For, one thing, the entire Balkan region has lived under despotic leaders whose goal for nearly 70 years was to keep history under wraps.

Following in Tito’s repressive footsteps, Slobodan Milosevic used many of the same tactics when he took power in 1989. He jailed journalists who criticized the regime and ordered the assassination of a prominent editor, whose murder remains unsolved. When hundreds of thousands protested his war strategies in Belgrade in 1991, they were gassed, jailed or labeled as “outside agitators,” perverts, drug addicts or enemies of the state.

Similarly, when Milosevic tried to steal the 2000 presidential election, he branded protestors as unpatriotic and ordered the sacking of newsrooms and anti-regime radio stations, and wiretapped and threatened members of a youth resistance movement.

With records of one of Yugoslavia’s darkest periods now accessible at the archive, there is hope that citizens of Serbia and the region may finally get the historical reckoning so long denied and continue their slow march toward a truly transparent, open society, Presnall said.

These potentially transformative events in Serbia dovetail nicely with the Knight Foundation’s global push for open-records laws, technology tools and a media trained to speak truth to power.

Knight had also hoped the archives would encourage in-depth and investigative reporting on Serbia’s military, but here results are mixed.

The reasons are myriad and complicated. Journalists do report the findings of both the Secret Graves and War Crimes commissions and do cite the military documents used to corroborate findings. But ownership of media is not transparent, newsrooms are strapped for resources and most reporters — paid below subsistence wages — frequently work more than one job to keep afloat economically. For these reasons and others, a strong tradition of watchdog journalism has yet to evolve.

And in practice, most journalists are unlikely to make the 40-minute car trip to Zarkovo, “unless they know there’s a big payoff,” said Ivana Micevic, a reporter for the Belgrade daily Novosti who is one of a handful of journalists to visit the archives. The fact that 50 years “of our history remains classified is a also problem,” Micevic said, echoing a concern raised by others in the media.

With unemployment in December 2010 hovering at 26 percent and the pace of reforms sluggish at best, “it’s fair to say reporters are more likely to want to train their rage and limited energy toward the current political elite,” rather than on understanding the past, said Marko Milosevic of the Center for Security Policy.

Legislation to open classified documents after 30 years – currently stalled in Serbia’s Parliament – is critical to changing the press’ attitude, as is a new law to formally wrest the archives from military control, said Cvetkovic, the historian who heads the Secret Graves Commission.

“Archives are independent, public institutions in all democratic countries. Serbia needs to get on board,” he said.

Commenting on the overall impact of the Zarkovo archives on regional relations and the practice of everyday journalism, media consultant Dragan Kremer said, “Certainly, there’s a strong potential for a searchable archive to help the warming of relations between Croatia, Bosnia, Kosovo and Serbia… At a minimum, the archive could put some facts right on all sides,” referring to the bloody wars of the 1990s.

However Kremer, a former journalist who for years directed media training programs in the region for the International Research and Exchange Board (IREX), said the profession of journalism “has yet to rise to the standard where journalists would use the military archive, even if they knew about it. Which they don’t.”

For whatever reason, publicizing and marketing this resource has not been a top priority of the Ministry of Defense to date. Similarly, journalists who do get MOD’s permission to visit the archive are trained only in technical aspects of the system: how to search the database, scroll and flag documents, and how to print or save documents to a disc.

Missing is any organized effort to train journalists in how to verify, cross reference and contextualize information they find in the military archive. Put simply, trainings have yet to materialize that teach reporters — too young to remember Tito or even Milosevic’s early days — how to interpret historic military records and events in the context of reporting on complicated defense issues in present-day Serbia.

Even if such trainings were available, Kremer is not sure reporters would use what they learn. IREX and other international media groups recently ran several in-depth reporting workshops in Serbia and then tracked the impact on actual daily journalism.

“Our research showed most Serbian journalists had no motivation, were not professional enough, and/or forgot about [investigative] tools much sooner than anyone expected,” Kremer said.

For his part, Jefferson Institute’s Presnall never envisioned that the MOD project would “develop journalists or journalism,” but rather would provide “good tools” for journalists to use as the profession evolves.

“You can argue that there are not enough good journalists [in Serbia]. But, as they emerge this fantastic tool will be ready for them,” he said.