1 millionth viewer takes orchestra worldwide

The death of classical music is an evergreen story in music literature. Graying audiences and diminishing funding sources have been the subject of stories dating at least 90 years.

As is often the case, technology has created new challenges, but also unexpected opportunities.

The Detroit Symphony Orchestra has embraced them, and is now celebrating 1 million views of its “Live From Orchestra Hall” webcast, touted as the first from a major American orchestra, online, for free. The webcast is funded by Knight Foundation.

But the news is not just about viewers or the potential for reaching a global audience.

In a video commemorating the moment, Detroit Symphony Orchestra´s president and CEO Anne Parsons notes that the orchestra’s presence on the web “has had a huge impact.”

“Our tickets sales live go up every single year […] and I know statistically that they come to more live concerts because they are watching us on the web.”

It is an intriguing turn of events. The storied Detroit Symphony Orchestra, which had its first concert in 1887, really did have a near-death experience in February 2011, when a musicians’ strike led to the cancellation of the remainder of the 2010-11 concert season. But the parties reached an agreement two months later and concerts resumed. That April, on its return, the orchestra offered its first live webcast. Webcasting is more common with European orchestras (the Berlin Philharmonic’s Digital Concert Hall is arguably the gold standard) but it is not a common practice in the United States. Costs, as well as technological, legal and labor issues, have made it a special occurrence.

Moreover, offering a free webcast of the orchestra’s performances might seem a counterintuitive strategy to bring audiences back to the concert hall. But then again, to regain and expand its audience, the Detroit Symphony set out to become “the most accessible orchestra on the planet,” and launched additional initiatives such as the Neighborhood Concert Series. Taking a chance with new technologies also had a precedent for the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. In 1922, the orchestra offered the world’s first radio broadcast of a symphonic concert. It was the technological leap of the time.

“The facts are simply that we have continued to sell more tickets since we started this program,” said Marc Geelhoed, the Detroit Symphony Orchestra’s Director of Digital Initiatives.

“Probably it’s not easy to measure any direct correlation […] and of course there are all kinds of things that go into classical marketing, selling tickets and audience development, but that’s simply what we have seen. There are stories of people checking out a concert as part of a webcast and then buying a ticket.”

Geelhoed estimates that about 4,000 people watch each “serious classical” webcast. The numbers may seem modest but the impact is not.

In an interview with MusicalAmerica in 2015, Parsons noted that “Pre-strike attendance was about 50 percent of capacity. Now we have more than 90 percent of the hall sold on a regular basis.”

Geelhoed noted that the orchestra webcasts “one concert of each of the subscription series classical programs, an educational classroom series concerts and also some special events.”

A survey of Michigan viewers suggested that the free webcasts made them more likely to attend a concert and a study conducted last year noted that “online streaming is the backup mode of attendance, not a replacement. It keeps patrons engaged and possibly makes them desire in-person attendance more.” On average, the survey showed, “DSO patrons streamed 6.3 concerts in the last year.”

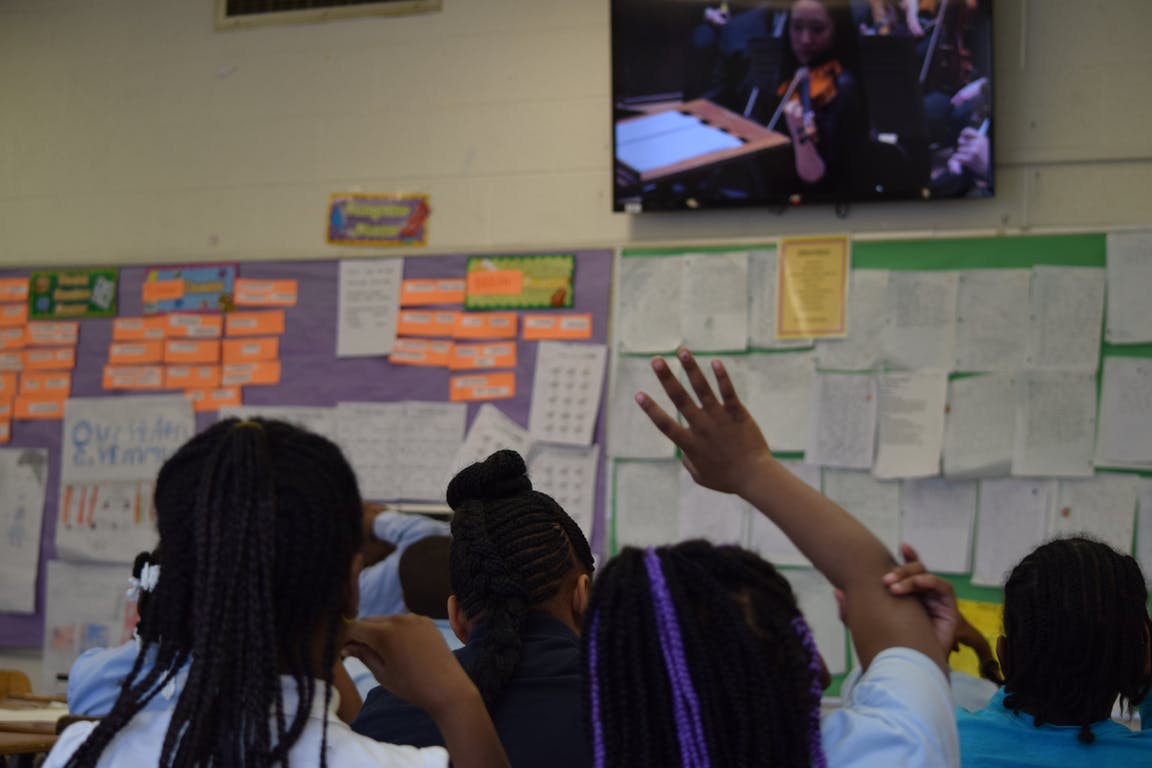

The idea of webcasting Live From Orchestra Hall has also yielded an educational component, the Classroom Edition, now in its third season, which offers interactive daytime webcasts for students and teachers and is funded by the Mandell and Madeleine Berman Foundation.

“Students have been coming to Orchestra Hall since the early 1900s, and now we have the webcasts,” notes Caen Thomason-Redus, director of community and learning, setting the educational webcast as an evolution and expansion of the orchestra’s Educational Concert Series, which brings Detroit students to the hall to see the orchestra. “The idea is trying to give them something to latch on to and pique their curiosity about the concert experience.”

On average, he says, the series has reached 40,000 viewers per webcast.

The concerts feature a host, interaction with the musicians on stage and interactive elements. Also, as a concession to a shorter attention span, the concerts have a quicker pace and pieces tend to be four minutes long or less. While the teacher’s resource guide is downloadable, the video is not, explains Thomason-Redus “but it does remain in the website, so they can review them. We still have all our classroom webcast there.”

Webcasting, which helps elevate the orchestra’s global brand, also opens these educational experiences to students around the world. When the percussionists of the orchestra, on their own time and with their own funds, went down to Nicaragua to work with a youth orchestra students, they discovered that “they were actually watching our webcasts,” said Thomason-Redus.

“We are not expending additional efforts to reach an international audience, but I can tell you that we have people in Norway, Japan, Kenya, Cameroon, Australia, all over the world watching these webcasts,” said Thomason-Redus. What happened with the youth orchestra in Nicaragua is, “an example of all these strands that are out there that we are not always aware of.”

Fernando González is a Miami-based arts and culture writer. He can be reached via email at [email protected].

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·