“All the Time in the World” at the McColl Center

Time. It is a concept with which we are all familiar. We count it. We waste it. We watch it go by. There is a right time and a wrong time. You can even be behind it or ahead of it. But do we really understand it? Do we all even have the same understanding?

Two artists, Gail Wight and Mary Tsiongas, examine these perceptions and understandings in an insightful exhibition at the McColl Center for Visual Art (a Knight Arts grantee) titled, “All the Time in the World.” Running from January 25 to March 23, “All the Time in the World” broaches this concept from an artistic and scientific point of view using video, installation and mixed media.

This exhibition presents a variety of perspectives on time. While there seems to be a central theme in Tsiongas’ pieces and Wight’s pieces, they are varied either through medium or subject in such a way to communicate different ideas and expressions of time. Wight who is an Associate Professor of art and art history at Stanford University conveys understandings of time using scientific knowledge and classification systems. Tsiongas’ work is more concerned with the relationship between time and change, particularly as it relates to the relationship between humans and the natural world.

Wight’s work “Living on Air” uses a flat screen television to show an HD video looping through a series of shots of lichen. The lichen appears to be on a rock face and very subtlety, very slowly it changes. The action is so gradual it leaves the viewer wondering if they really just witnessed any change, but as you continue to watch, it becomes evident: change is happening.

Watching lichen may seem highly un-artistic and in general one of the most boring activities possible. But through the magic of technology the lichens’ changes are sped up, and you become mesmerized by the lichens’ magnificent colors: bright neon yellow and green, soft orange, grayish-blue, and white spread and recede across the screen. This piece is all about the perception of time. We often mark or measure time by the changes that occur, but what about the changes that we miss? Nature is constantly changing. How long does it take us to notice?

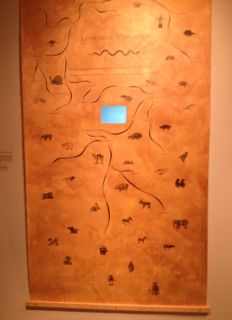

“Linnaeus Unbound” Gail Wight 2001.

Other of Wight’s works more closely deal with scientific notions of time- both evolutionary and generational. “Cabinet of Curiosities” and “Linnaeus Unbound” point at an impetus underlying these two notions: the way humans create knowledge of time through classifications systems, ownership and record keeping.

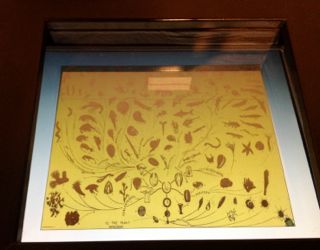

“Cabinet of Curiosities” Gail Wight 2001.

An interactive CD Rom and a wooden cabinet make up “Cabinet of Curiosities,” which is a modern take on a 17th century mode of collecting. Cabinets of Curiosities were created as Europeans worldview expanded through global expeditions; rulers, aristocrats and wealthy merchants created collections of natural specimens, art objects, antiques and geological artifacts. These collections were almost encyclopedic in content and the precursors to early museums. By owning, classifying, preserving and displaying these objects, Europeans could structure knowledge of the new and unknown.

“Cabinet of Curiosities” Gail Wight 2001.

The “Vanish series I-III” by Mary Tsiongas who is an Associate Professor of electronic media at the University of New Mexico presents a different approach to time. These works are presented on LCD monitors in elaborate frames with a video image playing. In the image a contemporary person preforms a variety of activities sometimes just standing and staring against a painted backdrop. The backdrops, however, are loaded with meaning, since at least two of them are paintings from the Hudson River School.

“Vanish I” Mary Tsiongas 2007.

The landscapes of the Hudson River School only capture a moment in time. The combination of the titles and the burning away of the “canvas” in “Vanish II” hint at the ever changing quality of nature like Wight’s earlier piece, while the inclusion of a contemporary person in these scenes presents an incongruity. These people seem displaced — alien to the world around them. They are in the wrong time or perhaps ahead of the times. Either way the “Vanish series” suggests an interesting relationship between humans, nature, and time.

With so many perspectives on and different understandings of time as presented in the McColl Center’s new exhibition, “All the Time in the World,” the visitor is left wondering are we really so familiar with it after all?

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·