Charles Beneke’s ‘Specter’ on display at the Akron Art Museum

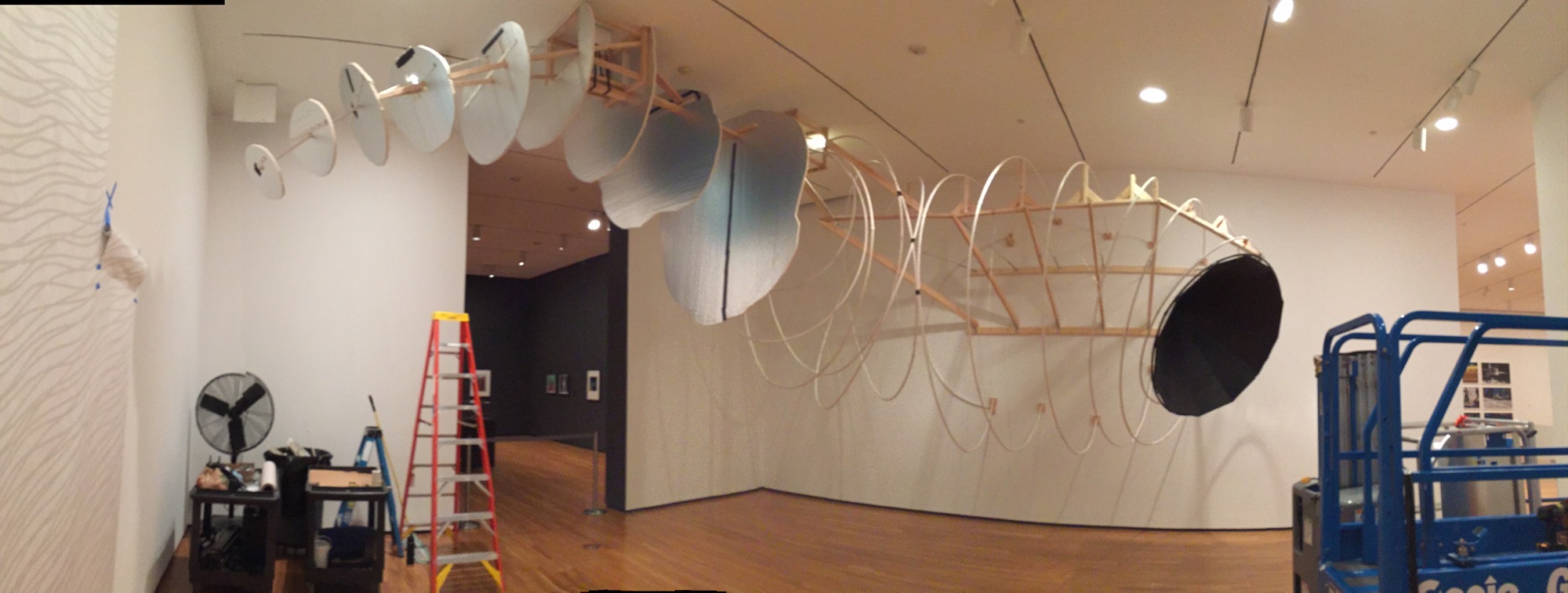

Photo: Installation artist Charles Beneke builds the framework for his installation art work “Specter.” Photo courtesy of the artist.

During a recent visit to the Akron Art Museum, which received a $750,000 grant from Knight Foundation to support “groundbreaking exhibitions,” installation artist Charles Beneke was putting the finishing touches on a massive work called “Specter.” In putting it together, Beneke has used one thousand feet of wallpaper and 60 woodcuts, from which he fashioned repeating images on a fabric-like material called Tyvek that has been used to make disposable clothing, among other applications.

Of late, print makers are starting to “take things off the wall” for installation pieces, Chief Curator Jan Driesbach told me during this same visit. They have tended to do that in small steps, she commented, but the museum wanted to give Beneke the opportunity to “take a big leap off the wall.” And that he has done.

“Specter” is a stunning, monumental and complex installation. The work fills the Judith Bear Isroff gallery on the second floor of the museum. Aesthetically and intellectually, it fills the imagination–creating, as Beneke has hoped, a consideration of global warming, climate change and their causes.

Charles Beneke, “Specter” in Akron Art Museum. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The work begins on a 20-foot gallery wall covered with wallpaper that depicts a lush, verdant forest of green leaves on deep brown trees, against beautiful blue skies. Several panels later, the imagery slides into different wallpaper illustrating an orange-brown array of panels with rising skyscraper images and black drilling wells. Beneke is able to segue the series by repeating the brown of the trees and reforming them into the skyscrapers, which in turn move on to skeletal frames of oil rigs and a bleaker landscape.

Shortly thereafter, the panels begin to lift off the wall and spiral into a vast cone that looms through the upper gallery space–growing ever darker in color as images of oil rig scaffolding become an abstract rendering of polluted clouds. The work ends in a vast vortex of black that hovers off the gallery floor just above the heads of viewers. Beneke built the ever-widening cone himself from a series of disks.

The imagery is as clear in its meaning as it is clever. The work appears huge, almost as overwhelming as the problem it seeks to capture in art.

Several things call for further explanation in the work. Why wallpaper, one might ask, as I did. Beneke commented that, were you to walk into someone’s house and see wallpaper on the wall, you’d pretty much be able to tell the year it was put on and when the house was built (if it hadn’t been altered). Wallpaper, Beneke said, carries information about who we are and how we live. In this work, it is a depiction of the current state of affairs with regards to the central problem addressed; it’s a narrative of who we are globally and how we got here.

Charles Beneke. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Wallpaper, too, is repetitive. Beneke took that idea and applied it to the span of panels that illustrate that global warming didn’t just happen. It has taken years. Beneke supports that notion by showing fragments of the oil rig images as the panels move along. They look like atomic particles. They seemingly float into the atmosphere until they amass densely into something more ominous. Interestingly, Beneke incorporates the prevailing wind pattern in the Akron area into the composition, if for nothing else than to drive the point home that we are all affected.

The growing scale of the blackening cone underlines how the problem is mounting as time goes by. The gathering vortex is created by layering pattern on pattern from the 60 woodcuts. The effect is of excess, in one instance, and massive build up in another.

Beneke spoke to the question of why he made destruction so beautiful. He commented tellingly that it can be. Rising smoke from factory stacks can make beautiful patterns in the clear blue sky–until you realize what’s going on, and until the consequences start to settle in. Even pollution, he added, has a glitter about it.

In the largest sense, Beneke is hoping that people see that we are all part of the problem, and can be part of the solution. He commented that most think of climate change as a kind of television issue, where we watch, blame large businesses and wonder who is going to do something to fix it. We all caused it, and we all can fix it, he implied.

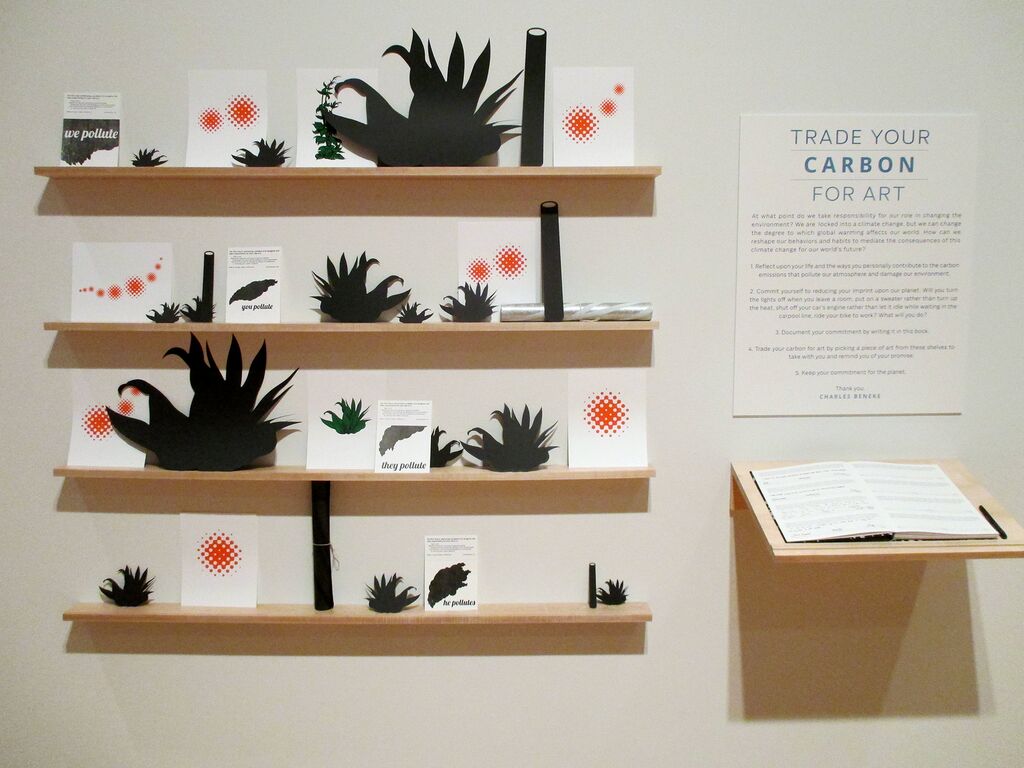

Visitors are invited to take away small print from the exhibition. Photo courtesy of the artist.

To that end, Beneke has created a book. (A professor and printmaking area coordinator at the University of Akron, Beneke makes books and does bookbinding as well.) He and the museum are encouraging people to write in it, saying what small thing or two that they will do to help reduce the problem. Even though global warming may be beyond preventing, it is possible to control what happens from here on, Beneke commented.

When people write in the book, they are free to take one of the prints located on shelves against the wall of the gallery as a gift from the artist. Beneke’s “Specter” invites participation by allowing visitors to walk under and around the spiraling vortex, and by taking away with them something more concrete than a memory of the work.

In conjunction with “Specter,” Beneke is maintaining a website with installation updates, news articles about climate change and related current events. He will also continue dialogue about the exhibition: There is an artist’s talk scheduled for Sept. 13 at 2 p.m. “Specter” will be on display through Jan. 3.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·