Civic Bright Spots Show Where Local News is Making Progress

Despite their struggle with shifting business models, there are bright spots in nonprofit news, collaboratives and crucial reporting on the front lines of COVID-19.

Although the collapse of local news during the coronavirus pandemic has been the dominant narrative in media circles, with gloomy forecasts for civic engagement and understanding, the Knight Foundation, local funders, universities, activists and others have been galvanizing resources to turn some of these news deserts into what we’re calling “civic bright spots.”

From Philadelphia and Chicago to Charlotte and Macon, these are areas around the country where different models of collaborative and solutions-oriented journalism are emerging, and putting their focus on COVID-19 coverage. The challenges and triumphs of these bright spots — and the distinct “power sources” they are relying on — suggest that the path forward for local news, although bumpy, may go through new territories.

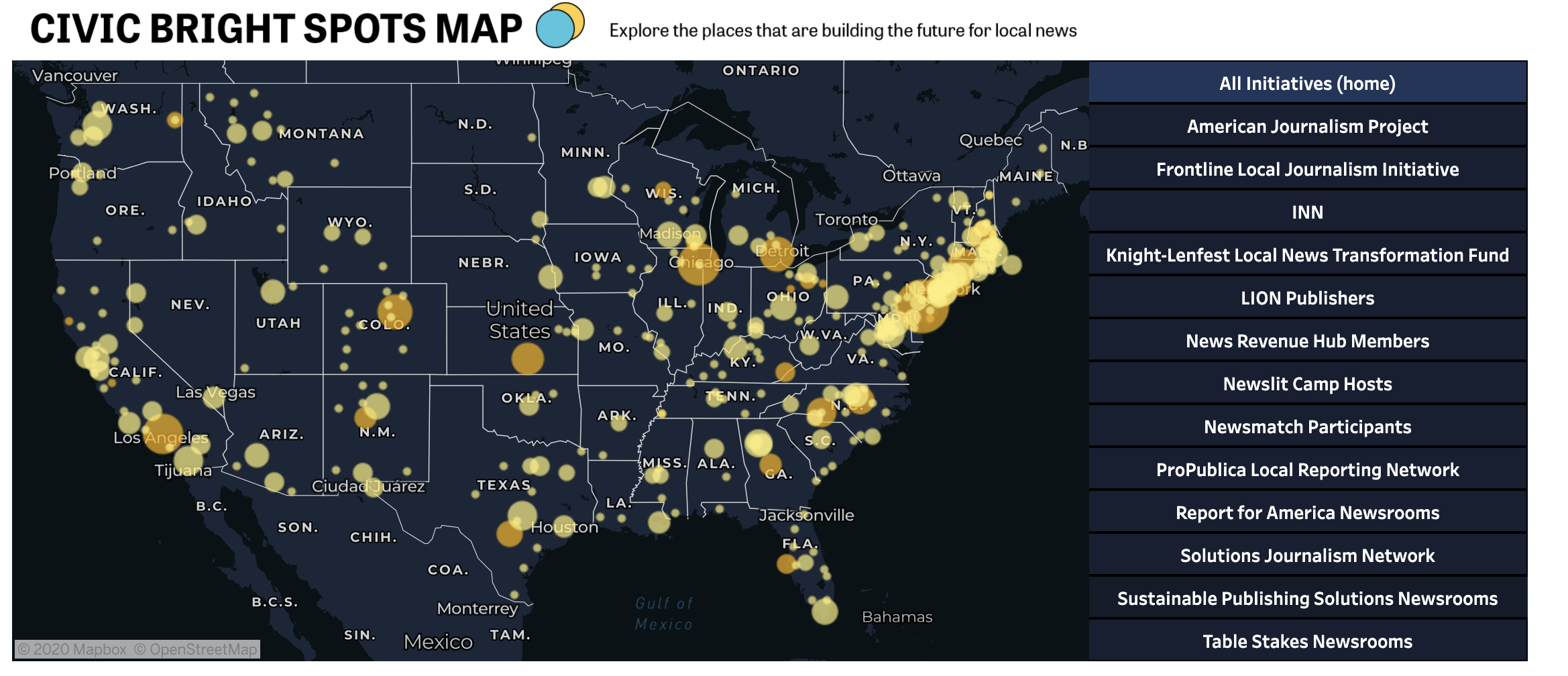

The interactive Civic Bright Spots Map shows just how many outlets in the highlighted communities have been touched by grants, memberships, collaboration and other Knight-funded initiatives to help support local news. While there are large numbers of local news organizations in the Northeast – and Philadelphia in particular – that have been part of these initiatives, the bright spots light up every state in the union, including Alaska and Hawaii. And while there have been closures of many print newspapers and alt-weeklies around the country, the media outlets on the map have largely remained resilient and in business.

These new models in local news often involve considering journalism as a public good, indispensable to the life of the community to the extent that it is part and parcel of the community. This means that newsrooms ought to employ members of the community, or make use of the spaces within it. Chicago’s City Bureau, for example, trains and hires citizens to cover public meetings. The public library in Charlotte has become a go-to destination for media partners to convene engagement events (with virtual town halls now) or discuss best tips and practices.

Some of these collaborative initiatives, such as Resolve Philly (which has covered criminal justice and poverty issues), have directly influenced policy and legal changes on the ground. And newer collaboratives are helping drive deeper coverage in Wichita, Kansas, and Northeast Ohio, with state-wide initiatives in New Mexico, Montana and Connecticut. The collaboratives include a mix of for-profit, nonprofit and public media outlets, along with local foundations, ethnic and community media – all focused on solutions journalism for communities.

The truth is that these collaborative efforts are mostly nascent, they may struggle with funding, and are sometimes messy at the start. And collaborating means going outside of journalists’ comfort zones, working with competitors and breaking down mental barriers. The key to these approaches is to maintain open communication, so that everyone can understand each others’ needs and priorities. Here are some of the notable bright spots featured on the Civic Bright Spots Map.

Philadelphia

Key players: Resolve Philly, Lenfest Institute, Independence Public Media Foundation, Temple University, WHYY, The Philadelphia Inquirer, local NBC and Telemundo affiliates, ethnic media

Unique power source: Thematic projects that coincide with timely news funded by a cooperative group of place-based funders

Resolve Philly‘s flagship program, the Resolve Philadelphia Collaborative, originally started as a project of the Solutions Journalism Network and involves more than 20 newsrooms focused on bringing solutions-oriented reporting directly to local communities. Its projects speak to the experiences communities are grappling with as they try to shift policy in new directions. The Reentry Project, a series of articles on the experiences of the formerly incarcerated, debuted in 2016 just ahead of Philadelphia’s District Attorney election. Resolve’s 2018 project focusing on economic security and mobility, Broke in Philly, is now in its third year and has its own dedicated website that features cross-published content focused on economic justice.

After COVID-19 hit Philadelphia, the Resolve collaboration focused intensely on health information needs of its most vulnerable neighborhoods with a new Equally Informed Philly project. The project includes a community FAQ that can be posted on any website, with questions coming in via text and other means, with partner newsrooms answering those questions in the FAQ and with deeper stories. The FAQ covers questions on unemployment, child care and worker’s rights and more, with a helpful map with resources around the city.

Resolve has also created a fantastic “Multicultural COVID-19 Campaign” toolkit to help spread messages about social distancing into immigrant communities in five languages. The graphics include a call to text questions for the FAQ. Resolve co-executive director Jean Friedman-Rudovsky says that getting information into vulnerable communities is a matter of life or death now.

“We know that there are information gaps and mistrust between government and communities and media and communities,” she said. “That can always be a life threatening gap, and at this time, the consequences are even worse. If at a time of pandemic there are folks who are most vulnerable and not receiving the information they need, then we need to work with community organizations that are trusted and need to be amplified. We see ourselves as the backbone of an information response to this pandemic.”

One of the major funders and hubs for local journalism in Philadelphia has been the Lenfest Institute for Journalism, which created a timely Philadelphia COVID-19 Community Information Fund. And one of its grants will help the Philadelphia Inquirer create The Inquirer Community News Service, which will support the Spanish-language El Inquirer; a community Q&A platform called Curious Philly using Hearken; and a series called “From the Frontlines” with coverage of workers and communities dealing with the pandemic. Other recent Knight-Lenfest grants for collaborative journalism and the amplification of diverse and under-represented voices have gone to WURD, WHYY, Resolve Philly and Temple University.

Philadelphia has become a true bright spot with all the attention being paid to collaboration and engaging and serving communities. Sandra Clark, vice president for news and civic dialogue at WHYY, told me about how a community essay by Dr. Hannah McLane on distributive justice sparked more coverage that led to action and impact.

“The essay was published on WHYYNews, which led to an interview on WURD Radio, the only African American owned and operated talk radio station in Pennsylvania,” Clark said. “And that inspired local surgeon Dr. Ala Stanford to start the all-volunteer Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium to help meet testing needs in black communities. To date the consortium has tested over 5,000 people in partnership with local black churches.”

Denver

Key players: Colorado Media Project, Gates Family Foundation, Rose Community Foundation

Unique power source: Regional funders and local support from businesses, individuals and foundations

With fiscal sponsorship from the Rose Community Foundation and launch support from the Gates Family Foundation and the University of Denver’s Project X-ITE, the Colorado Media Project has not just assembled journalists and newsrooms, but also community and business leaders, local foundations, professors and others into fighting to preserve local news. This broad coalition is distinctive from other civic bright spots in that it’s not just a newsroom-focused initiative, although its mission matches the concerns newsrooms across the country are facing: The Colorado Media Project (CMP) was born out of the deep cuts that were happening in local media across Colorado, especially at the Denver Post. Everyone could see that the pages of the local newspapers were getting thinner and thinner as other newsrooms simply shut down.

CMP was already incredibly active with events, research and collaborations, and planned a new COLab News Hub for many partners in a new space at Rocky Mountain PBS. The COLab is still planning to open in September, but CMP and its partners quickly ramped up as a virtual hub when COVID-19 hit, creating a new state-wide COVID-19 Coverage Network, with newsrooms sharing their stories with other local news outlets via the Associated Press’ StoryShare system.

“There’s this urgent need in our community for trustworthy, reliable local news,” said Melissa Davis, acting director of Colorado Media Project. “The future COLab tenants met over Zoom and asked about how we could strengthen each other’s work. But the crisis got them thinking even bigger: Newsrooms across Colorado are offering their COVID coverage for free, so why not team up with non-tenants like the Denver Post, Colorado Public Radio and 9News? We should all be talking about how to come together to cover the COVID-19 crisis. The AP is one of our tenant partners and they suggested using StoryShare, and we got it up and running in a week.”

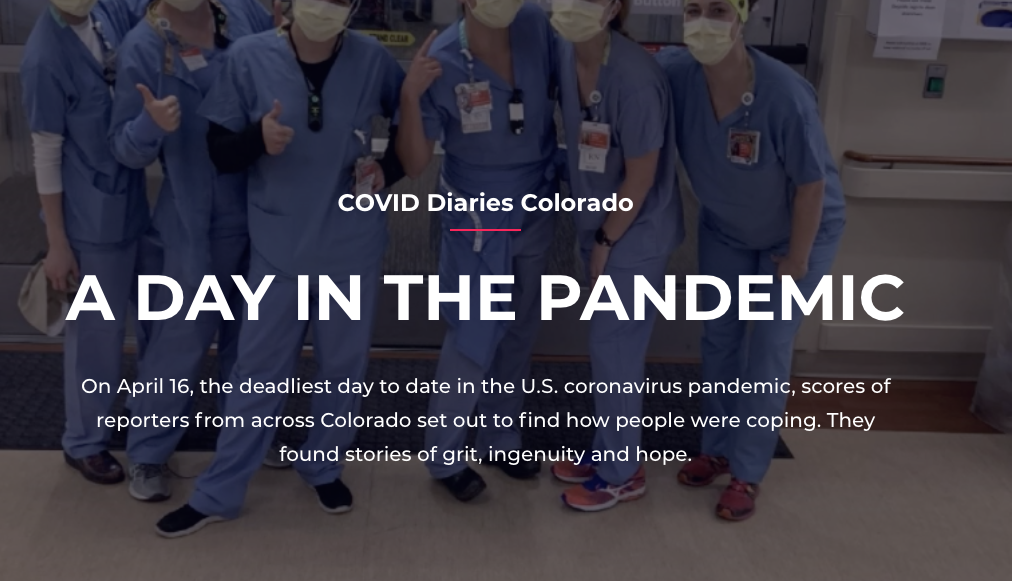

Once the COVID Coverage Network was up and running, each partner began putting its content up for others to publish and localize as needed. And then on April 16, COLab partners decided to run a collaborative project called “COVID Diaries Colorado,” with personal stories about how people were dealing with the pandemic, and participants such as a veterinarian, a health care worker and even the mayor of Denver.

CMP has also awarded $50,000 in grants to eight local news outlets and nonprofits, many serving immigrant communities with vital COVID-19 information, to join the COVID-19 Coverage Network. Grantees include Southern Ute Tribal Radio, Denver Urban Spectrum and Que Bueno 1280 Radio.

“I’m really excited about this new work, because CMP has been largely focused on sustainability in mainstream media, and we haven’t a lot of bridges into underserved communities,” Davis said. “Hopefully this will give us some entry points and help us build some trust with these media outlets that are incredibly important to their communities.”

Detroit

Key players: BridgeDetroit, Detroit Public Television, Michigan Radio, WDET, Wayne State University, Outlier Media

Unique power source: Walk the talk of reflecting the diversity of the community and putting their needs first

The Detroit Journalism Cooperative, a partnership of five media outlets, was born in the aftermath of Detroit’s 2013 bankruptcy. Its focus is to report on and create community engagement opportunities related to the city’s bankruptcy, recovery and restructuring. It was funded by the Knight Foundation, the Ford Foundation, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

One of the standout projects the Detroit Journalism Collaborative produced was a cascade of stories on the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Detroit uprisings, according to Moore. Although the media outlets worked on distinct pieces, they all came together in a way that added to a broader narrative of the history of the uprisings.

But the Cooperative never really collaborated in deep ways besides having the partners cover the same topic at the same time. And there was never a separate entity guiding its existence. That has changed with the recent announcement of BridgeDetroit, a new multi-platform outlet focused on Detroit that will also run a Partner Network with 26 news and nonprofit members and counting. Long-time Detroit journalist Stephen Henderson is the project executive and executive director, and told me that 100% of the staff hired at BridgeDetroit reflected the majority of the city, which is 77% African American.

“We wanted it to be multimedia, because one of our imperatives is that this content should find Detroiters where they are, and not have to pull them to another space,” Henderson said. “We want to reach them very easily, so you have to be on many different platforms. And it’s not just words on the page, but sometimes stories are visual stories or audio stories.”

Right as the project was coming to fruition, COVID-19 hit Detroit and Michigan hard, and the focus has been on covering it – not only as a public health story but about the collateral damages wrought by the coronavirus.

“The housing market is changing really fast because of the housing crisis that was here before,” Henderson said. “Food insecurity has cropped up in a way that no one could have imagined. Food banks are overrun with requests, and are literally running out of food. We’re covering that and trying to help people identify places to fill that gap. Unemployment here, we published a story recently about the unemployment rate in Detroit is 48% which is really mind-blowing.”

The next project the Partner Network will tackle is a way to re-envision digital obituaries with a tool to help Detroiters mark the deaths of people who died from COVID-19, and memorialize them. BridgeDetroit is working with the Wright Museum of African-American History to make the memorials part of the museum. “It’s a really interesting and poignant example of a difference in approach [from traditional journalism],” Henderson said. “I’ve worked in newsrooms for 30 years, and it’s not the way we’ve been doing things in the past.”

Chicago

Key players: City Bureau, Block Club Chicago, Hearken, Chicago Reader, WBEZ, Vocalo

Unique power source: Employing citizen journalists to keep tabs where newsrooms can’t

The large Midwest city on Lake Michigan has a long history of strong local media, but its largest newspapers have been in decline. There’s a more recent history of media innovation, with the EveryBlock startup and the Block by Block conference (that morphed into the LION Publishers Summit). And lately, the focus has been on media startups that help enable engagement and conversation (Hearken), explore alternative funding models (Block Club Chicago) and even train citizens to report (City Bureau).

Founded in 2015 and based in the South Side of Chicago, City Bureau Chicago is a nonprofit civic journalism lab focused on bringing journalists and communities together. It operates civic reporting programs; hosts a “public newsroom” where journalists and members of the public can convene to talk about local issues; and recruits, trains and pays Chicagoans to monitor local government in its Documenters program. City Bureau Chicago receives funding from various national, family and place-based foundations, and it accepts individual donations as well. And in 2019, earned revenue from consulting and licensing related to its programs became City Bureau’s fastest growing area of revenue.

Harry Backlund, City Bureau director of operations and business strategy, said that the nonprofit’s direction came out of a survey of Chicagoans who said they were upset with local media coverage.

“In Chicago, the public will is extraordinary,” he said. “In 2018 we worked with the Center for Media Engagement to survey 900 people in Chicago. Some of the results didn’t surprise us—folks in Black and Latinx neighborhoods on the South and West Sides were by far the most frustrated with media treatments of their neighborhoods. What did surprise us is that the same people who were most frustrated by media coverage were also the most willing to volunteer their time to support local journalism. That really inspired us.”

Since the pandemic struck, City Bureau has launched a COVID Resource Finder with more than 1,300 neighborhood, city, state and country resources sorted by who is eligible, what’s on offer, languages spoken and location. It’s a database approach to resources that others have put on maps. Plus, City Bureau has started an Information Aid Network, assigning Documenters to call Chicago residents with limited internet access to find out their information needs.

The nonprofit has expanded to support a Documenters program in Detroit along with Citizen Detroit and WDET that is entering its third year, and this year they are launching a pilot in Cleveland with Neighborhood Connections. But they also realize they have to make sure they keep local networks strong.

“Chicago media has huge challenges,” Backlund said. “A lot of groups here are doing great work to create a better system that really works for people — but there’s so much work to do.”

Charlotte

Key players: Charlotte Mecklenburg Library, The Charlotte Observer, WFAE, La Noticia, QCity Metro, Free Press

Unique power source: The library as neutral ground for civic support and civic engagement

When people don’t trust the news because the media has become hyper-politicized, where do they go?

For the partners in the Charlotte Journalism Collaborative, including The Charlotte Observer, WFAE and La Noticia, they went no further than their local library.

Sponsored by the Solutions Journalism Network and the Knight Foundation, the collaborative’s goal is to strengthen the connections between reporters and the public. A library has meeting and event spaces, and data and resources. But it also attracts a wide variety of people and is one of the most trusted community organizations, said Seth Ervin, chief innovation officer at the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library.

While the library seems a natural destination for locals looking to discuss civic issues, he said, the library must also figure out the kind of added value it can bring to a journalism collaborative. In this case, it is not only a convening space in real life but also hosts the website for the work of the Collaborative.

Libraries are a natural repository for information, but don’t really fit as newsgathering and reporting operations themselves. “I think my concern would be that it can’t be the local news,” he said. But “they [libraries] can definitely be a platform for it.”

The Collaborative has pivoted to covering COVID-19 with three virtual town halls with their community, asking people what they need and also inquiring about creative solutions and resiliency. Those sessions (with highlights here) led to many story ideas for the Collaborative, which also produced a bilingual program to bring in a Spanish-speaking audience.

“Through the combined efforts of the Charlotte Journalism Collaborative partners, we are able to tell the full story around COVID-19 – how it is impacting our communities, how we keep our citizens informed and protected, and how people are making a difference in their neighborhoods,” said Chris Rudisill, the new director of the Collaborative. “When media outlets work closely together and involve the voice of community members, the impact of local news can match even the most difficult challenges we face.”

New Hampshire

Key players: Solutions Journalism Network, New Hampshire PBS, Manchester Ink Link, The Berlin Daily Sun, Business NH Magazine, The Eagle-Tribune, The Keene Sentinel, The Student Journalism Coalition.

Unique power source: Collaboration as a statewide initiative with local partners

The Granite State News Collaborative, New Hampshire’s statewide multimedia news initiative, focuses on using coordinated reporting and engagement activities to highlight issues of local importance, especially those that have been underreported elsewhere. Its first project, Granite Solutions, was funded by the Solutions Journalism Network, and members of the collaborative to do in-depth reporting on behavioral health to better understand the issue.

Thinking beyond local into something more statewide has been an interesting trajectory, said Carol Robidoux, editor and publisher at Manchester Ink Link, one of the collaborative’s partners. Partnering hasn’t always been easy — but it’s paid off in the long run.

“A lot of the boundaries that exist are boundaries that you’ve kind of created yourself, or that have been imposed upon you by decades of construct that is no longer the only way to do things,” she said. “The limits are those that you will accept… if you’re willing to push those boundaries a little bit, you may find there’s no limit to what’s possible.”

After March 12 when the pandemic hit New Hampshire, the Collaborative put all its focus on covering the COVID-19 crisis, with 17 media outlets – along with the New Hampshire Press Association and Franklin Pierce University’s Marlin Fitzwater Center – sharing more than 365 stories so far. Robidoux says they’ve basically created a state-wide press service in the process, with 20 freelance writers around the state creating 10 stories per week for all the partners to publish.

“That turned out to be key to saving journalism here in NH in some ways, as at the same time many of our member outlets made the tough decision to lay off or furlough staff,” Robidoux said. “Without reporters, there are no stories. The Collaborative saw a way to keep reporters working and provide rich content for members by securing additional grant funding to be able to hire furloughed reporters and freelancers to produce local and statewide stories for the Collaborative.”

And they’ve been creative as well, launching the following:

- A web-based public affairs show with New Hampshire PBS highlighting the work of partners.

- Two massive data projects looking at what has worked (and not) with remote learning, and the economic impact of the pandemic on communities.

- A Spanish language audio broadcast of daily COVID news, and a Spanish translation of their partners’ COVID-19 pieces.

- Two video projects related to visuals of the response to the COVID-19 crisis around the state, and the fears, hopes and resilience of the 2020 high school graduates.

“All since March 12. All because we are working together. There’s no telling what we can do next,” Robidoux said.

Macon, Georgia

Key players: Knight Foundation, Mercer University, Macon Telegraph, Georgia Public Broadcasting, WMAZ, Peyton Anderson Foundation

Unique power source: The university as a communication hub to facilitate partnerships

What started as a partnership with Mercer University’s Journalism and Media Studies program, the Macon Telegraph and Georgia Public Broadcasting in 2012 is now the Center for Collaborative Journalism, based in Macon, Georgia. The mission behind the collaborative is to both transform journalism education and strengthen community engagement, with partners focusing on a topic emerging from the community, using a “teaching hospital model” approach to journalism.

Like other collaboratives, the Center for Collaborative Journalism has worked with the Solutions Journalism Network on a project focused on youth violence and solutions. But it’s also been working on community engagement projects around access to food and health issues around food, said Debbie Blankenship, director of the Center, and has covered residential blight, pedestrian safety and the resegregation of the local school system.

The collaborative essentially operates as a nonprofit newsroom, she said, and employs a civic reporting fellow to report the stories other collaborative partners aren’t able to cover. Recently, the Center updated and re-branded its Macon Newsroom page, which showcases the work of the collaborative, and has put COVID-19 coverage front and center for all the partners.

For the upcoming mayor and commission elections, WMAZ, the local CBS TV affiliate, organized “listening labs” around the county in February and used the issues raised in interviews with candidates. After the pandemic hit, they finished those interviews via Zoom and shared the interviews with all the partner newsrooms. One of Macon’s largest hospital systems, Navicent, was not releasing data on COVID-19 cases, so the partners filed a joint Open Records Request for data, leading to more cooperation from Navicent, according to Blankenship.

“We still haven’t gotten all of the data but the request certainly carried more weight with multiple media outlets filing together and the hospital,” she said.

The partners have also shared audio, video and photos from interviews related to COVID-19 coverage, and the Mercer University students have made a series of “Quarantine Video Diaries.” Blankenship noted that Georgia Public Broadcasting recently shared a story on “How to Get a Coronavirus Test in Georgia” that was shared on all the partner sites.

“It’s been an interesting time for our collaboration as there is even more uncertainty about the long term viability of local news outlets,” Blankenship said. “However, we’ve amped up our collaborative efforts for the first time in the partnership to extend outside the engagement projects.”

Wichita, Kansas

Key players: Wichita Community Foundation, The Active Age, Solutions Journalism Network, KSN, Wichita Eagle, Wichita Public Library, AB&C Bilingual Resources, Wichita State University, KMUW, The Community Voice, The Sunflower and Kansas Leadership Center

Unique power source: Community partners help reach a diverse audience

As one of the newer bright spots on the block, the Wichita Journalism Collaborative seems to have learned the lessons of other collaboratives around the country. It started out with a series of meetings with journalists and community stake-holders. It involved the local public library and journalism school. And the Solutions Journalism Network provided a $100,000 grant to kick it off this spring.

According to Amy DeVault, project manager of the Collaborative and journalism instructor at Wichita State University, the grant was just going through when the pandemic hit, and they fast-forwarded to launch with a focus on COVID-19 coverage.

“We rewrote our proposal, crafted a memorandum of understanding and got a commitment from seven Wichita media outlets and three community partners to work together and share resources, creating the Wichita Journalism Collaborative,” DeVault said. “We’re working through the nuts and bolts details right now — what is shared, the editing process, how/where we share, etc. The more of that we get out of the way, the more fun it becomes, because we’re finally starting to focus more on the reporting and how we can make collaborating pay off for the newsrooms and for the community.”

Not only is this a collaborative born during the pandemic, but it’s also one that is perfectly suited to reach a broad audience in Wichita. As DeVault points out, there’s a daily newspaper, a local public radio station, a major TV station – and smaller niche publications serving college students, the African-American community and older Wichitans. The Wichita Public Library will support the collaborative with research and resources, along with boosting community engagement around reporting projects. Plus, AB&C Bilingual Resources will make sure partner stories are translated into Spanish and also “provides a direct channel to a large and underserved population,” according to DeVault.

“Barely out of the gate, we already have reporters from different publications partnering up to work on stories, and it’s exciting to watch them put their strengths together to try to create something better than either one could have alone,” DeVault said. “I look forward to digging into a project where every partner is involved in some way.”

Mark Glaser is a consultant and advisor with a focus on supporting local and independent news in America. He was the founder and executive director of MediaShift.org.

Local and Nonprofit News

Media organizations around the world face a crisis in building sustainable business models and building audiences. Nonprofit news ventures in the public interest are on the rise, often filling the gaps left by traditional news organizations with diminished resources. At Knight Foundation, we explore how local journalism is changing in a globally connected world, supporting new approaches and models that help meet the information needs of communities. (Photo by The Texas Tribune via Flickr)

3 Ways Local News Initiatives Are Serving Crucial COVID-19 Information to People in News Deserts

Engagement collaborations, texting platforms, community media are trying to reach people in underserved communities where journalists are scarce. Living in San Francisco, I have a lot of news sources to find out how the coronavirus is affecting my community. There’s the main San Francisco Chronicle website and app, which has provided COVID-19 case maps down […]

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·