Cuban and U.S. entrepreneurs exchange ideas during Miami visit

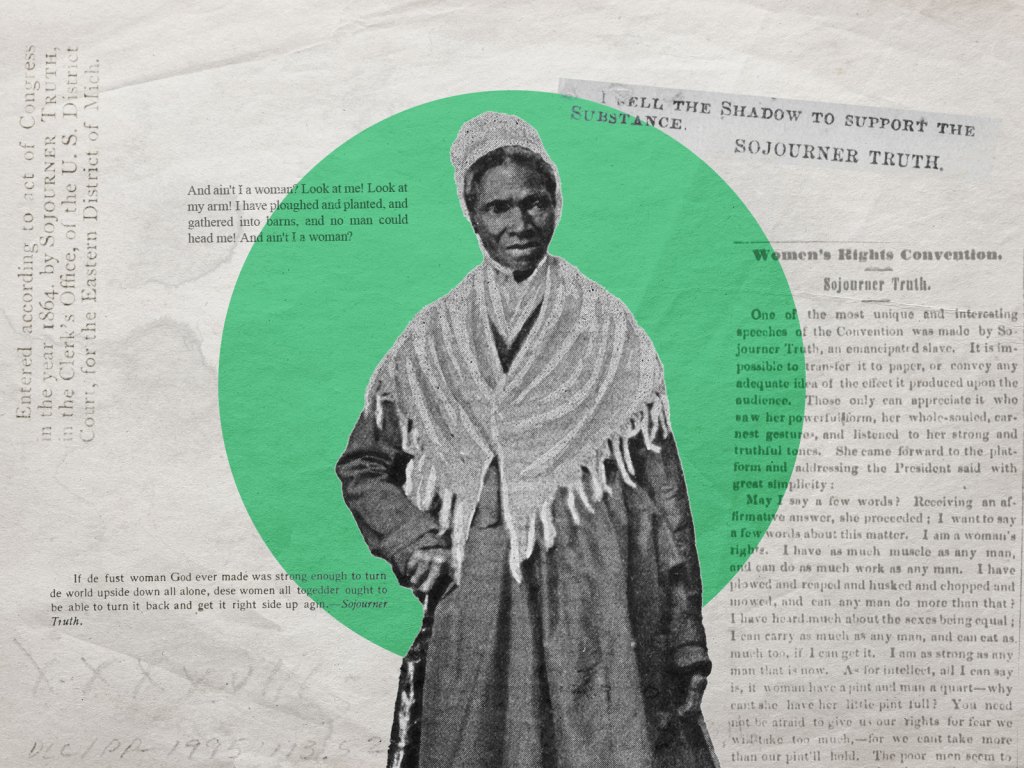

Vanessa Pino helps a cook prepare icing for pastries. Courtesy Cuba Study Group.

Let others consider the national and global political implications of the thawing relations between the United States and Cuba. Ruben Valladares looks at the small paper tray for french fries as he’s having lunch at a Pollo Tropical and wonders aloud how he might produce them back at his shop in Havana. Sitting next to him, Niuris Higueras — who runs Atelier, one of the best restaurants in Havana, just patronized by New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and his delegation in their recent visit — was considering the cost benefits of using paper plates with real silverware.

For entrepreneurs, and perhaps especially for these entrepreneurs, there is no lunch break.

The challenges for micro-empresarios in Cuba are many, some obvious, some easy to overlook for people living in an open, consumer society. But so are, suddenly, the opportunities — and there’s much to catch up.

Higueras; Valladares, who runs a company that prints and manufactures promotional containers; Caridad Limonta, whose company makes clothing; Vanessa Pino, who runs a business gift-packaging pastries; and Victor Rodriguez, who crochets bikinis, all with businesses in or around Havana, were in Miami in early May, visiting as part of the Cuba Entrepreneurial Exchange, meeting with local business people in similar lines of work to share experiences and ideas.

They were also part of a lunch at the recent eMerge Americas conference where they discussed their business and the challenges they face under Cuba’s political and economic conditions.

This visit was the second of such encounters. A group of five business women, including Higueras, visited last August. The members of these groups represent the leading edge of the cuentapropistas, the self-employed, a budding sector in the Cuban economy that began to emerge in 2008, after the government decided to allow private microenterprises.

The exchange, funded in part by Knight Foundation, is a project of the Cuba Study Group, a nonpartisan nonprofit based in Washington.

“We decided to focus this time on entrepreneurs in the non-service sector,” explained Tomas Bilbao, executive director of the Cuba Study Group. “These are what we call ‘makers,’ people who make products inside Cuba. It’s only in the most recent reforms that businesses that actually produce products were authorized, and people are interested in seeing how they manage to create and manufacture in a country that has so many challenges in terms of access to raw materials, machinery, credit and so many other things. This [exchange] highlights not only the ingenuity of Cubans but also the creativity and the products they can offer.”

Cuban-American businessman Carlos A. Saladrigas, chairman and CEO of Regis HR Group and chairman of the board of the Cuba Study Group, noted that the response of the Cuban-American business community in Miami has been “very positive.”

“I think they can look at these people and, in essence, see perhaps where we were many years ago, struggling to build our businesses,” he said. “These are the pioneers. These are the guys who are breaking ground, the vanguard. There is a civil society being born [in Cuba]— and all this has enormous implications for the future of the island.”

Each one of the Cuban participants in this exchange had a remarkable story to tell and each story spoke of profound, historic changes writ small, in people’s everyday lives.

Caridad Limonta, once a vice minister of light industries, quit her government post after a nearly fatal illness made her rethink her priorities. Considering her alternatives, she turned a sewing machine, her mother’s gift after her graduation as an engineer specializing in textile manufacturing, into a business.

“It had been on a corner gathering dust for almost 30 years,” said Limonta, who had reached the post of director in a state-run company. “But when I saw it I thought: ‘This is my salvation.’ I knew many clothes-manufacturing places were closing and that there would be many women at home without work, and that most of them had a sewing machine in their houses and I thought they could be my workers — and today they are.”

Vanessa Pino, an industrial designer by training, turned her knowledge of marketing and her passion for pastries into a business. She gift-packages her cookies and cupcakes to order and “most of my clients are other entrepreneurs,” she says.

The irrepressible Victor Rodriguez, an energetic, talkative, natural-born salesman who was addressed throughout as “Victor Bikini,” was a college math professor. After 25 years, he lost his job in 1997, in what is known as Cuba’s “Special Period” following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

“We had to keep on living,” reflected Rodriguez. “So I started selling cheap trinkets in this little stand, 4 square meters and trying not to starve to death. That’s how Victor Bikini started.”

Rodriguez decided that to succeed he had to “find a market making something different, so I tried bathing suits. And I tried yarn. I tried crochet bathing suits.” After much trial and error he arrived at the right design — providing proper coverage — and material — the thread used in shoe laces.

In Havana, he suffers from a lack of materials, he says, a common complaint for all participants, and space limitations. “I’m here representing, in fact, a group of artisans working at the warehouse where I am,” he said. “And I can tell you these are all people with incredible initiative and creativity. But right now we are bumping against a ceiling. The day we could break through, and that’s why I’m here, I truly believe we’ll have many good things to offer.”

Ruben Valladares, who runs the company that prints and manufactures promotional containers, is a sociologist by training who worked for 30 years at the Telecommunications Investigation and Research Institute, and also has a master’s degree in business, economy and financial management. He started his business three years ago and now has “nearly 50 workers.” As he describes his shop, he notes that he built the machines he now uses; while his list of clients include major international brands, he concedes that the work is still “artesanal, homemade. But to get big you have to think big.” He has also created a program in a school where fifth- and sixth-graders are taught how to make paper products.

“I don’t do that just for fun,” says Valladares. “Besides what it represents to me in terms of personal satisfaction, it’s a way to present a different image of private business, of self-employment. It’s a way of changing minds and opening a space for change.”

In fact, for all the challenges these entrepreneurs face back home, Saladrigas, the chairman of the board of the Cuba Study Group, says, “The most important obstacle is philosophical. There is still a government [in Cuba] that looks at this as a necessary evil not as a good thing. This needs to change. This mindset needs to change. Like all pioneers [these entrepreneurs] probably have arrows in their back, but are really blazing a new trail. They are not a ‘necessary evil’ but the saviors of the Cuban economy.”

Fernando González is a Miami-based arts and culture writer. He can be reached via email at [email protected].

Recent Content

-

Community Impactarticle ·

-

Community Impactarticle ·

-

Community Impactarticle ·