Musical plants at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

If you are a resident of the earth, you are also part of what is known as the biosphere — the thin layer of the planet’s surface, which harbors life as we know it. Many parts of the environment are gigantic, like an ocean, while others, such as bacteria, are too small to see with the naked eye. What is evident is that there is a give and take between all the elements in these living systems. Never was this clearer than in the exhibit “Quartet” by Data Garden at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, a Knight Arts grantee.

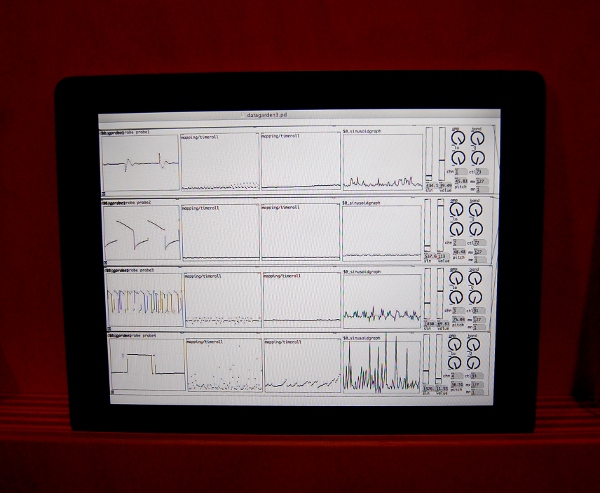

A team of five sound engineers, graphic artists and designers from Data Garden teamed up to help give a musical voice to our less mobile but equally alive cousins. With electrical sensors hooked up to the leaves of plants, the changes in the states of these organisms provided data, which was converted into sound audible on the human scale.

By the entryway to the Megawords space in the basement of the museum, a sign informs visitors that, “The music you are hearing is being generated by living tropical plants.” With a variety of ambient electronic sounds drifting through the surrounding area, visitors were more than a little curious and the organizers of the project were fully engaged with questions and discussions. A few seats and some piles of pillows in the room allowed listeners to recline and take in the often relaxing sounds emitted by the speakers. Other people stood and confronted the plants more directly by talking to them or touching their leaves. Occasionally the sounds would change significantly in response to the contact, proving that the plants were indeed reacting.

One big question to come up was whether the plants were aware of the humans. While there is no way to be sure exactly what level of awareness plants possess, their changes in electronic signals were more than likely responses to stimuli and not conscious decisions.

All living things are constantly receiving and sending out energy and signals in order to regulate themselves and manipulate their environment, and plants are no different. While a snake plant may not be able to chase down a gazelle, our photosynthetic neighbors do grow, move and heal. They convert light, water and carbon dioxide into energy and nutrients. And anyone who has ever studied bees knows that flowering plants have very complex relationships with pollinators, including chemical signals, sugary reward systems and ultraviolet color signals.

The changes in the land of flora are perhaps less perceivable than humans would like, however. A slowly moving vine doesn’t intrigue many people as much as, say, a leaping pod of dolphins. To compensate for this, the subtle electrical signals are converted and magnified through computers in order to make them musically viable; the plants are merely supplying data. Tropical species were selected due to the fact that they hold a lot of water and produce more activity compared to others, making them more likely composers.

Data Garden is also planning to revisit this project in a new light. Later in the summer, it will have a similar event in Bartram’s Garden, where the plants will be outdoors and in the ground instead of pots. This setting is potentially more dynamic and the location is more apt to percussive beats and glitchy noises than the user-friendly drones of the museum exhibit. Stay on the lookout for this and other upcoming Data Garden ventures.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·