‘Deep City,’ the story of Miami’s Motown

By Fernando González Miami arts & culture journalist

Well before Miami Sound became a brand name, there was a Miami sound.

It came together in the mid ’60s and it was soul and funk as only Miami could make it. It was raw and gritty. It was built on the sanctified grooves of church and street life, the brash sound of marching bands and the lilting cadences of the Caribbean. And because it was performed by local musicians, black and white, but also players from Alabama and Georgia but also Jamaica and the Bahamas, it had an accent all of its own.

It was the sound of Miami — and Deep City Records was its Motown.

“Deep City: Birth of the Miami Sound,” a documentary film directed and produced by local filmmakers Marlon Johnson and Chad Tingle and Dennis Scholl, is a valentine to the people, and the community, that created that music. It premieres in South Florida at the Miami International Film Festival on Friday, March 14, at 8:30 p.m. at the Olympia Theater.

“I’m a native of Miami, born and raised,” says Johnson. “Dennis is from here; Chad has been living here for the better part of two decades now. These are stories told by Miamians, about Miamians for the world at large, and we felt this was an important story to tell. For me, it was an affirmation of some of the things I’ve always known about the city.”

“You can hear it in the music: You can hear the Caribbean-Bahamian-Jamaican influences, the Latin influences, the black Southern gospel influences, all things we’ve grown accustomed to living in Miami and really stood out in those songs.”

Deep City Records was the brainchild of two school teachers, Willie Clarke and the late Johnny Pearsall. They became friends while attending Florida A&M University. Clarke, who majored in art education, was a lead drummer in the school’s fabled Marching 100 band and had a talent for writing lyrics and melodies. Pearsall, a business education major, didn’t play an instrument but was the guy who knew, and had, the latest hit records. Back in Miami, they started Deep City Records in the back room of Pearsall’s Johnny’s Records, a shop at NW 60th Street and 22nd Avenue in Liberty City.

It was the first black-owned record label in Florida.

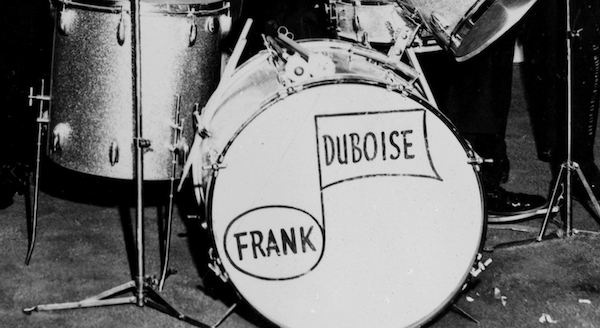

Deep City became a showcase for local talent such as Clarke; his songwriting partner and singer Clarence “Blowfly” Reid, a key figure in the Deep City story; as well as guitarist and singer Willie “Little Beaver” Hale; singer Betty Wright; and groups such as The Moovers, Them Two (a vocal duo) and Frank Williams & the Rocketeers.

The music was terrific. But by the late 1960s, lack of money and distribution, as well as differences between the partners on the future direction of the label, brought about the end of Deep City. In the early ’70s, Clarke and several Deep City artists, found a second musical life—and success well beyond Florida’s borders—with Henry Stone’s TK Records. (Clarke became a global hit-maker who won a Grammy in 1975 for “Where Is the Love,” sung by Betty Wright.)

Deep City received unprecedented national attention in 2006, when Chicago-based Numero Group reissued 17 tracks in its collection, “Eccentric Soul: The Deep City Label.”

Scholl, a filmmaker who is also Knight Foundation’s vice president of the arts, heard the CD, was bowled over by the music and intrigued by the story behind it; he called on Johnson and Tingle, with whom he had previously collaborated on “Sunday’s Best,” a documentary about the hat-wearing church tradition of African-American women. That project won a regional Emmy.

Still, the story of Deep City wasn’t an easy sell. It took three years. “We would not have been able to make this story without WLRN,” says Tingle. WLRN’s agreeing to serve as executive producer of the film proved key. “When we were looking for funding and an outlet, they really took a chance on us,” says Johnson.

The setting for the story is a vibrant Overtown, then the center of African-American life in Miami. “It was beautiful. Neon lights from one end of the street to the other. Second Avenue looked like Hollywood,” recalls Clarke at one point in the film.

Throughout, Overtown is a key character in the story.

“It was important from early on for us to really showcase black American life in the 1960s in the South, and in Miami specifically, in a positive light,” says Johnson. “When we did our research and found archival footage, it was refreshing for me to see these images of black people in an Overtown full of businesses, walking the streets, looking very dignified. It was an important part of the film, almost a subplot to the story.”

In fact, “Deep City: Birth of the Miami Sound” tells a music story while speaking about a community and its history. For Miami, a young city in constant, rapid change, reminders of what came before take on a critical importance.

“Miami has a young history, and I’ve always been fascinated with how it’s a history that happened in such a compressed amount of time,” says Tingle, a Miamian by choice. He was born in Jamaica, moved to New York when he was 10, came to Miami to attend college and has been living in South Florida for nearly 20 years. “People think about Miami music history and might think of KC [Harry Wayne ‘KC’ Casey of KC and The Sunshine Band] or Luther Campbell or [jazz bassist] Jaco Pastorius or so many other artists, but this is where it all started.

“Overtown and Deep City is the foundation. Even if many don’t know it and even if they don’t get the credit they deserve, it was important to me, to us, to cement this, because this is where a lot of what happened later came from.”

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·