Drawing whose Detroit? In conversation with Ben Bunk

Ben Bunk is a local working artist. Having grown up in New York, he left home at the age of 18, bouncing around the country before landing in Detroit a few years back. I caught up with Bunk at his home, which is also his studio. Over an afternoon of beer and coffee, our conversation covered a lot of ground. We discussed — among many other topics — the pressures on Detroit artists, the unique possibilities this city contains, speculations about where it might be headed and what it means to be an outsider here.

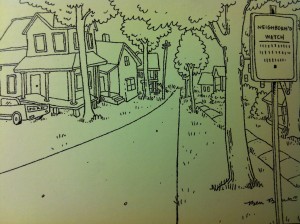

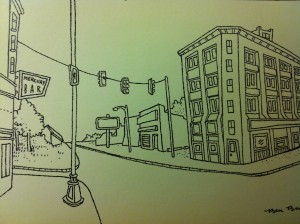

I first came across Bunk’s work at a Motor City Brewery show over the summer and was immediately taken with a series of drawings he did for a project called “Drawing Detroit.” Originally intended to be a coloring book — though in my opinion the images are good as is — the book contains a series of line drawings he did of the city, starting on his near-East block and illustrating every house and building as he made his way downtown. The images themselves are spare line drawings — which is what originally drew me to them — and, with their lack of right angles and straight lines, manage to capture the otherworldly feel of the city far better than a more precise representation would.

“Drawing Detroit” grew out of Bunk’s natural inclination to draw the houses in his neighborhood, along with the pressure he felt to do something to benefit and engage the community. The original piece was done on an unbroken 90-foot scroll of paper, which I asked him to take out of storage and partly roll out for me; sure enough, going down the middle of the scroll I saw house after house, beginning with his block and heading downtown. As he was unrolling it he pointed out one of the houses he used to live in and talked about what one of the buildings was once used for and what it’s used for now. It all seemed like a really excellent intersection of artistic inclination and community connection. Additionally, as an offshoot of the project, he had postcards made of several of the drawings — the idea being that people could send images of the city out into the world, to provide a different perspective of Detroit.

Although he’s currently earning a very modest living from the book, he expressed some concern about whether it was OK to earn money from a project so heavily based on Detroit, practically the definition of a hard-luck city, and one he’s not originally from. After all, it’s not his city. But isn’t it? We discussed at considerable length this question, the question of who Detroit belongs to, who can claim it as theirs. I should probably point out that I’ve only recently found my way to Detroit, having moved here this past summer, so I’m particularly curious about — and sensitive to — the subject.

The topic of outsiders — some would call it the problem of outsiders — never seems too far from a conversation about what’s happening in Detroit, and the concerns that people have are certainly not without reason. No one wants their neighborhoods (or galleries or coffee shops) taken over by people who don’t understand, or simply don’t care to understand, the many events that led directly to the present state of affairs, be it good or bad or something else altogether. The problems of gentrification are real, and complicated, and like most things come with competing lists of benefits and drawbacks.

Wendell Berry, the Kentuckian, the great and radical farming intellectual, has a unique way of defining ownership. For Berry, the true owner of a parcel of land is whomever will farm it, care for it and make it productive — whomever is willing to dig into the dirt, plant the vegetables and see them through to harvest. I’m fond of the definition, however radical and even troubling it might be, and the analogue relates to Detroit — with its truly impressive citizen farmers — beyond abstraction, becoming almost plain description. The abstract definition remains important, however, and I’d like to use that idea — that sense of care for one’s surroundings, the desire to make them productive — as a working definition of who can claim Detroit as theirs.

At one point in our conversation, Bunk told me that he believed Detroit was a place of unlimited possibilities. It takes a keen sensibility and strong imagination to visualize potential, not just in Detroit, but in general. It’s not unlike a farmer in her field, reaching down to palm a clod of dirt, and envisioning eggplants or green beans or squash, where everyone else sees only dirt. Of course, vision is only the beginning. The next stage is the work.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·