Edward S. Curtis’s native America that never was, on view at the Black Dog Cafe

I’ve been seeing Edward Curtis’s photographs of Native Americans my whole life; we all have, I suspect. I’d be hard-pressed even to say when I first encountered them, so deeply embedded are his iconic portraits in the warp and weft of our nation’s story of itself – a grade school history text? the natural history museum near my West Texas childhood home? So, I was deeply familiar with Curtis’s images, but until yesterday I’d never seen an entire exhibition’s worth of them in person – and I didn’t find them at a museum.

The Black Dog Coffee and Wine Bar, in partnership with Christopher Cardozo Fine Art (which claims to have the world’s largest inventory of Curtis’s original, vintage photographic prints for sale), just opened “Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian,” with, by my count, 24 large-format (and handful of them even “mammoth”) prints: lithographs, photogravures, silver gelatin and palladium prints, and a generous assortment of the Goldtones for which Curtis became famous.

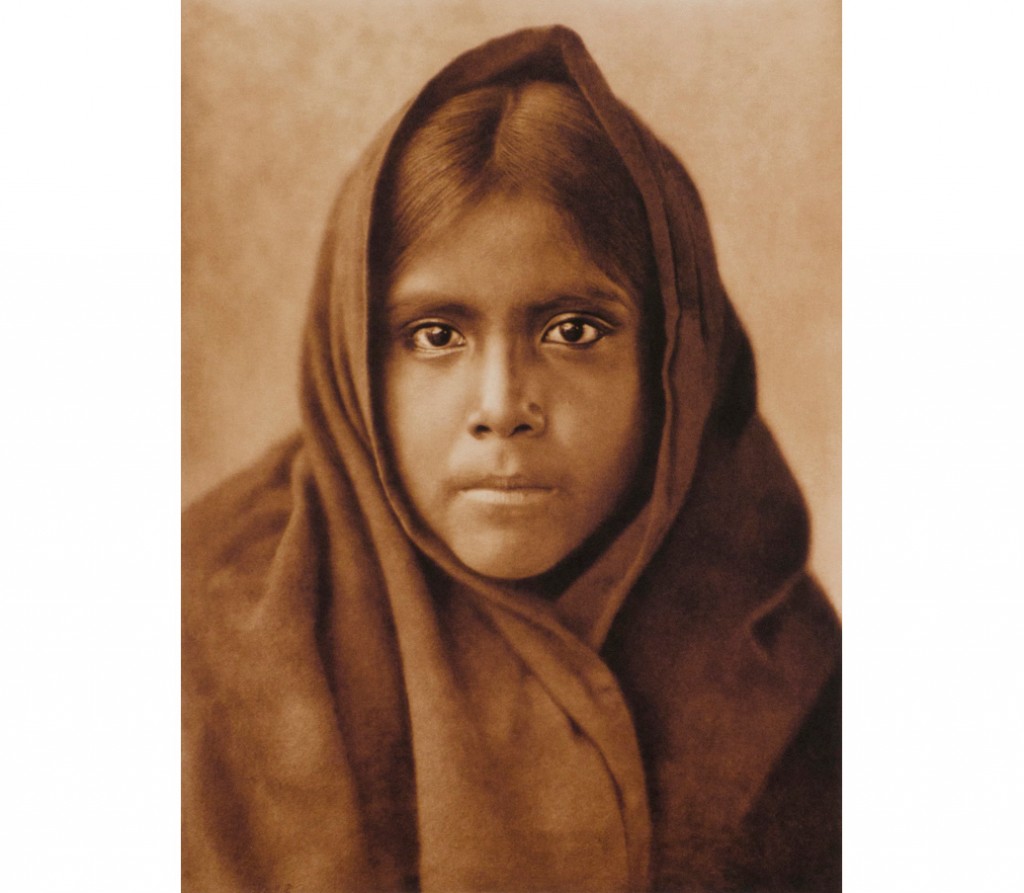

As the title of the show suggests, the photos are drawn from his vast “North American Indian” series, for which Curtis traveled the West for three decades at the beginning of the 20th century, documenting in now-famous portraits the various tribes and cultural traditions of the people who lived there. The photographs are riveting seen in person: warmly lit, marked by a graciousness of composition that invites a sense of immediacy, even intimacy. They are unabashedly romantic tributes to what Curtis dubs in one photograph “the vanishing race,” and his devotion to his subject is evident in every frame. He makes such beautiful pictures.

Edward S. Curtis, Three Chiefs (1900) Goldtone print. Image courtesy of Cardozo Fine Art

Actually, therein lies the source of my unease with these images. Let’s call it the “Kim” problem; Rudyard Kipling tended toward precisely the same sort of exoticizing and embellishment in that beloved novel about India. Both men conjure a powerful fiction about “noble savages” soon to be lost to history; both are wistful for some imagined, culturally pristine age, full of mysteries and wonders, that never actually was.

Curtis strikes me as a collector or Victorian-age naturalist more than he does an ethnographer. Like Audubon, he’s concerned with capturing perfect specimens, naming and tagging them, and in so doing, exerting a kind of ownership – “Hopi Man” or “Blue Jay,” there’s little difference in the men’s approach to their respective subjects. Curtis’s images aren’t photojournalism. According to information found his own notes and other, undoctored photographs from the same time, it’s clear these were carefully orchestrated tableaux – more like museum dioramas than documentary.

Blanket Weaver – Navaho (1904), palladium print. Image courtesy of Cardozo Fine Art

Curtis’s story-in-pictures spins a romantic yarn of unschooled tribes of people living close to nature, untouched by time, uncorrupted by foreign cultural influence but on the cusp of being overtaken by the modern world. But the story is Curtis’s, and the people caught by his lens are little more than characters given a part to play and a costume to wear according to the dictates of his telling. Any elements that didn’t fit that story were simply removed from the frame, through retouching if necessary – eliminating clocks and other modern devices the tribes had long since assimilated into use; erasing all trace of contact with the white settlers and traders with whom native people had been engaging since the 1400s.

Looking through the photos, I’m deeply ambivalent. Curtis’s work has a pernicious, glib sort of beauty. By its very appeal, the romantic tale told by his photographs has effectively overtaken in popular imagination the messier, less glamorous story Curtis’s subjects and their descendents would likely offer for themselves.

The Vanishing Race (1904), lithograph. Image courtesy of Cardozo Fine Art

I’m far from the first to make these observations about Curtis’s legacy. The exhibition at the Black Dog is important; seeing the Curtis photographs in the setting of a café is such an accessible, congenial way to spend some time with this historically and artistically significant work. But I wish the exhibitors would have included some reference to the critical conversation surrounding this work; instead, the accompanying didactic materials leave a casual visitor to presume Curtis’s photographs have been uniformly embraced. For me, both the work and the exhibition would have been richer, and more honest if they risked a bit of unvarnished candor.

An Oasis in the Badlands (1905), lithograph. Image courtesy of Cardozo Fine Art

You can see “Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian” through the end of August at Black Dog Coffee and Wine Bar at the corner of 4th and Broadway in Lowertown, St. Paul. For more information visit blackdogstpaul.com/index.shtml.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·