Enabling innovation in libraries

This post is second in a series about a gathering of library directors Knight Foundation convened in Miami Feb. 11-12, 2017, as part of its continuing work with libraries. Knight Foundation also recently released a report “Developing Clarity: Innovating in Library Systems,” and announced a package of funding to support innovation in libraries.

The second day of the Knight Foundation’s library directors’ meeting, on Feb. 12, began with “Making Innovation Happen in a Constrained Environment,” a mini-panel featuring Melanie Huggins, executive director of the Richland Library in Columbia, South Carolina, and Story Bellows, chief innovation and performance officer of the Brooklyn Public Library.

The session was moderated by Ryan Jacoby, founder of MACHINE, a New York-based strategy and innovation company.

Jacoby began by framing the discussion around the challenge of maintaining traditional library services while adding new activities and service innovation.

“This is an ongoing process,” Huggins said. “We are constantly reinventing how we reinvent. And so we’re learning as we go. And anything I share with you that sounds like, ‘Oh, man, y’all have got it down!’ No. No. It’s a constant process.

Huggins said a comment made the previous day by Felton Thomas, director of the Cleveland Public Library, struck a chord with her. Thomas had said that the Cleveland Public Library’s work was “tied to our strategic plan.”

“Our strategic plan is what guides our work,” Huggins said. It is not in addition to our work; it is our work. And it’s the same with the web-based service design and human-centered design in our library. It’s not in addition to our work; it’s how we do the work. I think, fundamentally, that’s how you get to the place where you can democratize. People start to understand that service design is a way to solve problems. It helps you examine all the process, even stuff the patron and the customer never see. Teaching our staff how to do that has been the biggest game-changer for my library system, probably in the last 30 years.”

Jacoby asked Huggins to expand upon that.

“Six years ago,” she said, “we went through a really extensive kind of rebranding process that started from the inside. It wasn’t, ‘Let’s put a new shiny logo on our library and call ourselves something different.’ It was a ‘We have to start acting like the library we want to be before we do that.’ We focused on the customer experience—the before and after of the customer’s journey with us: a customer getting a library card; a customer coming in for the first time; a new immigrant coming to the library. We took it about as far as we could go without some new tools.”

Adaptive Path, a San Francisco-based firm that specializes in human-centered design, spent about a year teaching “a core group”—about 25 out of a staff of 385—to use the method.

“We mapped that whole ecosystem out of who on our teams needed to know what,” she said. “Then we started investing. We chose people sometimes based on their aptitude… But then we let people opt in for the training as well.”

Bellows said finding that “‘coalition of the willing’ is really important, particularly at the outset, because we want to have real world examples where we can demonstrate that something worked on the ground. … It’s a much more compelling message when it comes from somebody’s peer saying that something is possible.”

“We have this amazing group of new librarians who have come into the system, who are really eager to do different things. They were a great coalition of the willing,” Bellows said. “One of the things we figured out quickly was that we needed the right incentives for branch managers who may not see themselves like the new folks who were getting training. They’ve done their jobs for a really long time, and we needed to find ways to engage them in this process and put incentives so that the success of one of their librarians was something that they were receiving benefits for as well. I don’t think we thought about that immediately at the outset.”

The Brooklyn Public Library had 60 branches involved in this process, Bellows said.

She added that the library relies on “the individuals at the branches who see challenges every day” to help formulate solutions and then library officials determine how to support their work. Bellows said that building cohorts of people across branches to collaborate on similar issues is also an essential part of their innovation strategy, along with providing librarians with new skills through professional development training to cover skills “such as community needs assessment, facilitation and partnership management. These are critical to being able to deliver new types of services and develop new types of programs.”

Bellows said finding community partners is another important part of creating capacity and broadening services.

“We have a lot of programs that are not traditional literacy programs,” she said in response to a question about how the library selects its programming when there are so many needs. “We have one where senior citizens come together for a virtual bowling league. This is a really, really wonderful program. We get people who are developing relationships with their neighbors that we may be able to use in other ways. We are not going to train our staff on how to be expert bowlers. … How do we facilitate that? How do we reach out and find the people who could be benefiting from that program? What comes next? What are the skills we think the library can bring to that?

“I think we look at that for a lot of programs, such as knitting and languages,” she said. “We don’t need to develop expertise and competencies in all of these different areas. We need to be able to identify the people in our communities who can do that on our behalf.”

Huggins emphasized the importance of hiring staff with diverse skills.

“We hire a few real librarians,” she said. “Then we hire people with other skill sets. I want to remind everybody that has real librarians in their library that they all have an undergraduate degree in something. They all know how to do other things. They may just have been at the library for a long time.”

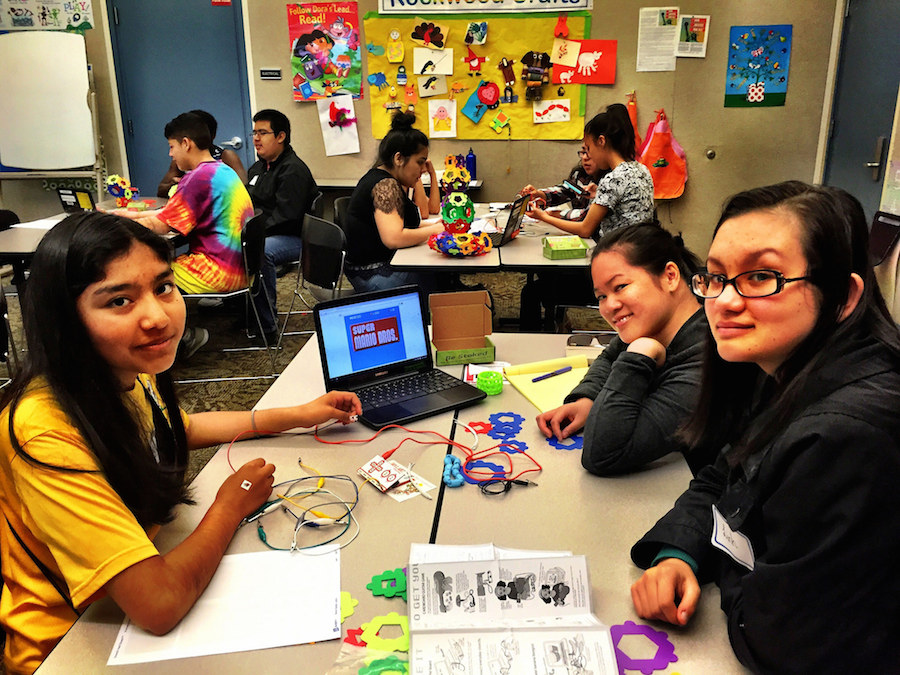

For example, the Richland Library main branch includes creative spaces, such as a makerspace, a theater and artist studios. They discovered that there were staffers who had a range of skills who could work in those areas, such as a graphic artist trained in computer-aided design and a textile artist who “actually shears her own sheep and dyes her own wool,” Huggins said.

“We had a lot of people that already had a talent and passion, and they weren’t using it in the job they were in,” she said. “So, about half of the team that’s there now transferred from other places.”

Huggins said the Richland Library’s ACE team—Advancing Customer Experience—is also thinking about ways of getting more people to use those spaces. “These are the people that are up-and-coming service designers. “We can log problems to them,” she said, “and let them kind of think about solutions. We’re constantly trying to get more people using these tools, wherever they are.”

That user-centered approach is also at the heart of the approach in Brooklyn, Bellow said.

“We’re constantly thinking about what the customer is thinking, feeling, and doing,” she said. “It’s about motivation, not outcomes. We can ask them questions about that, get them to tell us their journey.”

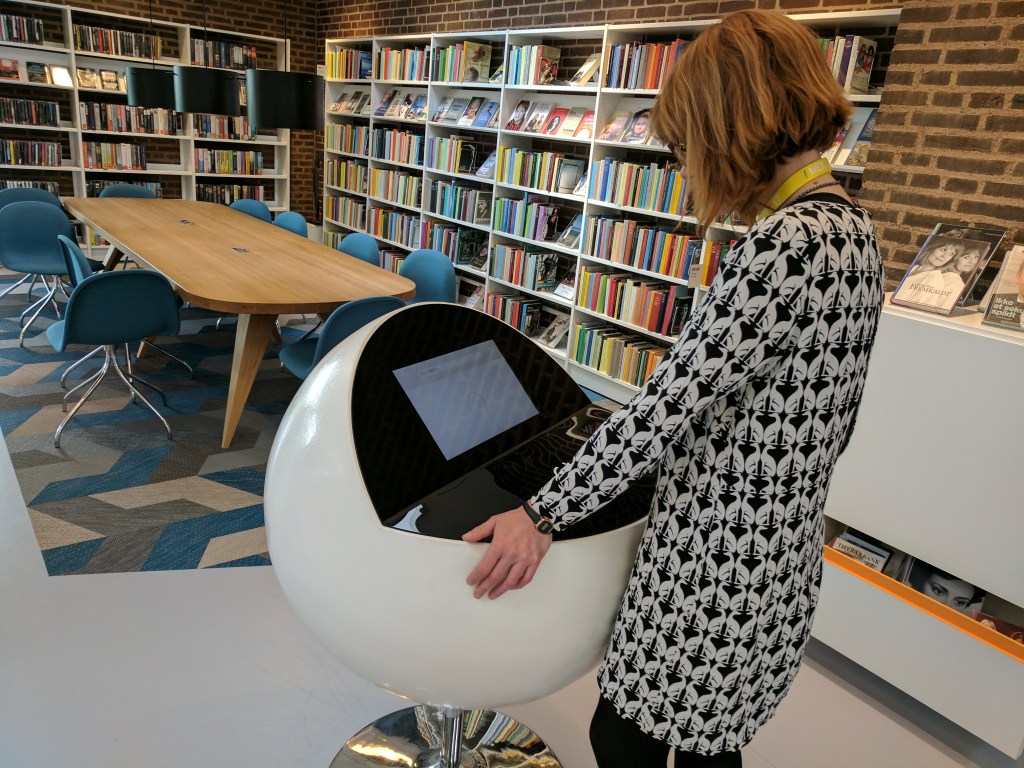

One example, Bellows said, is that they discovered people were putting materials on hold based on the title only to discover they were getting the wrong items when they came to pick them up.

“They meant to get the book, but it was actually the audiobook. Or they meant to get the DVD, and it was Blu-ray,” she said. “What they told us that we didn’t know was that our icons look too similar in our catalog. And they were too small. We would never have known to fix that little thing to make their experience better had we not asked them the question.”

“That’s not shiny new object innovation,” Bellows added. “That’s just listening and understanding and having empathy for what the customer is going through, and trying to make the details of the service better. That was an opportunity; it wasn’t a problem.”

Bob Andelman is a Florida-based freelance journalist and author. For more, visit andelman.com.

r

-

Information and Society / Report

-

Communities and National Initiatives / Article

-

Communities and National Initiatives / Article

-

Communities and National Initiatives / Article

-

Technology / Article

-

Technology / Press Release

Recent Content

-

Communities and National Initiativesarticle ·

-

Communities and National Initiativesarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·