Free speech and the urban-rural divide on America’s college campuses

On May 5, 2020, Gallup and Knight Foundation released a new report on college students and their attitudes about Free Speech. Sneha Verma. View the full report and additional insights here.

To better understand the attitudes of young people towards the First Amendment, a Gallup-Knight recent report surveyed 3,000 college students about their attitudes about freedom of expression. As a brown person who grew up in semi-rural Kansas (which is 85% white), the results are not surprising – it makes sense that college students’ views on the First Amendment and free speech vary based on gender, race and ethnicity. But there’s something missing in the analysis, and that’s an examination of how students from a rural background view these issues, versus students who grew up in diverse urban centers.

Urban-rural is not a proxy for liberal-conservative. But there are defining characteristics of rural communities, including lifestyle (rural residents are more likely to participate in their communities); economic well-being (rural residents are more likely to be in poverty and have lower salaries than their urban counterparts); and political affiliation (many residents of rural areas are registered Republicans even if their views may differ from the current administration).

As someone who grew up in Derby and Wichita, Kan., my willingness to express controversial views is likely more tempered than someone from an urban area, partly because of the nature of university life. Someone from a bigger area would probably be more confident to say what they think because they think their ideas would be validated. Anyone growing up in a rural area is raised with the idea that rural areas are on the fringes – so they are less likely to voice their opinions. Even more so if you’re a member of a minority group.

Until high school, my schooling had a mix of suburban and rural students – and not a lot of diversity. When I got to the University of Kansas, I found a divide that wasn’t exactly rich vs. poor or liberal vs. conservative. What I discovered, instead, was a divide based on how you grew up. Urban students dove right into the university experience, joining Greek life and all kinds of clubs. Rural students tended to not participate in those institutional activities. Each group not deliberately objecting to the other’s speech – but unsure of where their thoughts fit in with students from very different backgrounds. In areas with little formal institutional infrastructure, students can have a hard time making this transition and struggle to express their thoughts in a wider forum.

Most interactions between rural residents are on a smaller scale and the networks of acquiring and disseminating information are generally tighter-knit. The sizes of these communities are clear indicators of this, but so is the decline of local media.

A 2018 study by the University of North Carolina journalism school reported that since 2004, the nation has lost nearly 20% of their newspapers. Counties with no local news outlets are overwhelmingly rural, and state and regional newspapers no longer cover outlying areas. Students overwhelmingly stated that their discussions are shifting online. However, when nearly a quarter of rural residents lack basic broadband access, how can they be expected to keep up or contribute to the latest discourse? Strengthening local newsrooms and media outlets will allow for more informed discourse on college campuses as young adults from all regions of all identities flock to campuses.

How can colleges promote civility and healthy discussions on campus? The first step might be to see rurality as more than a tool for recruiting students. Administrators must concentrate efforts toward community building by encouraging rural students to join some of the groups and activities that define campus life – common book discussions or student organizations ranging from the student newspaper to community outreach organizations. While rural students have access to some of these institutional resources in their own communities, colleges rely on these activities to enrich student life rather than first establishing a core identity of belonging to the campus. Further, because they have more institutional resources and larger communities force people to form subgroups, urban students have had more opportunities to participate in those activities in high school, so it’s an easier transition.

Universities often approach students coming from rural communities as if they were from another country – come to our campus, abandon your foreign ways and absorb the urban experience. Instead, perhaps, colleges should take a cue from rural communities, where strong social ties through social institutions provide healthy, safe spaces for even challenging conversations. If more college students had those kinds of close connections that span gender, race and ethnicity, perhaps both rural and urban students would have a more equitable free speech experience on campus.

Sneha Verma is a junior at the University of Kansas and a former Knight Foundation intern.

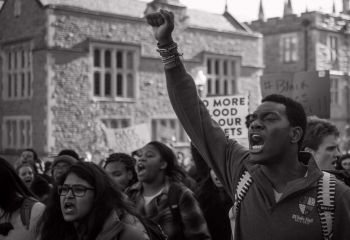

Photo (top) by Victoria Heath on Unsplash

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·