Getting our feet wet: Water sensing for journalism

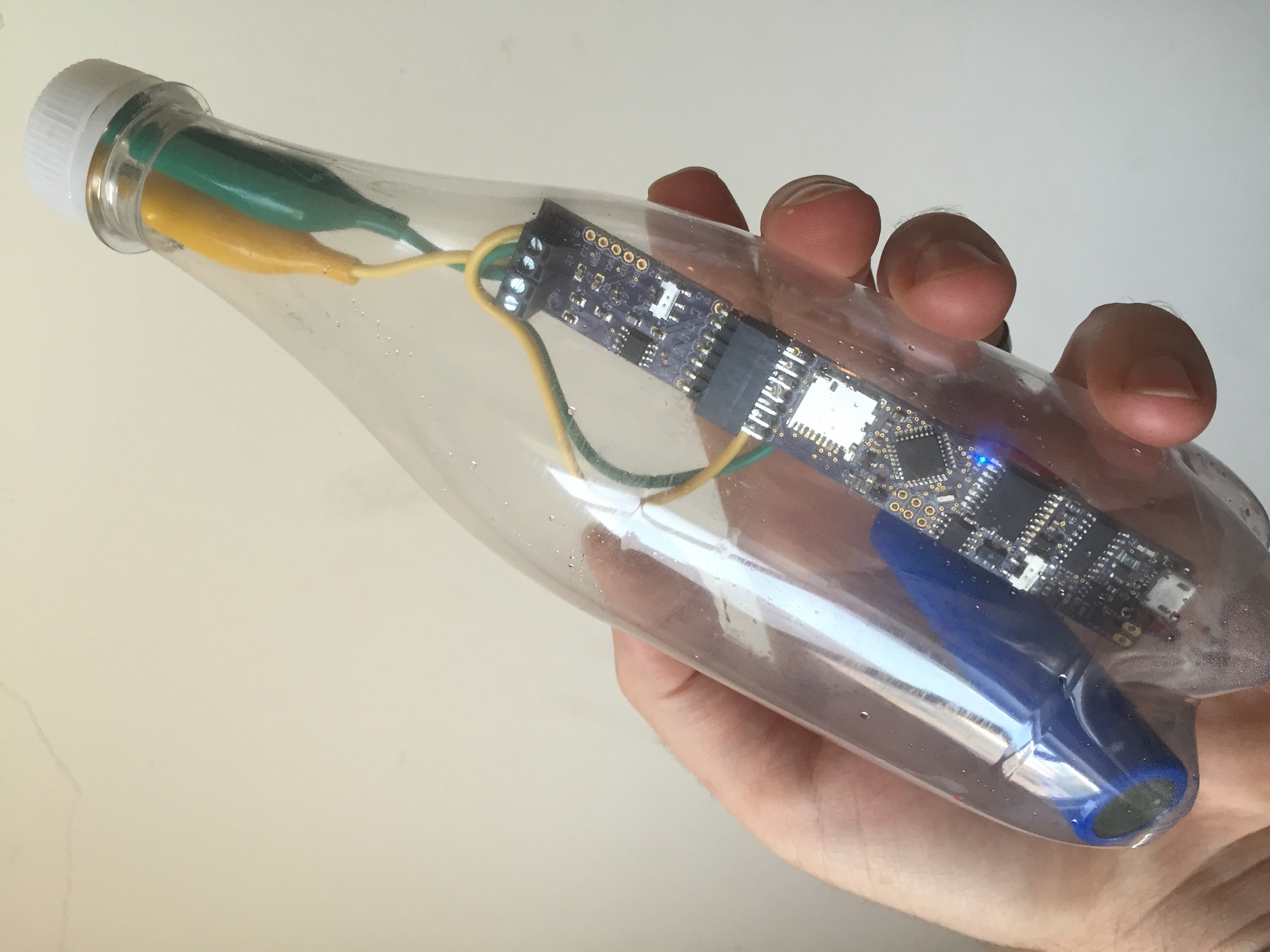

John Keefe is senior editor for data news at WNYC and one of the Knight Foundation-funded Innovators in Residence at the West Virginia University Reed College of Media. Photo: Don Blair building Riffle water sensors at MIT. Photo by John Keefe.

In a classroom uphill from the Monongahela River, we are doing sensor journalism all wrong.

We’re using untested, inaccurate water-sensing devices, we don’t have a solid story to pursue and we probably will fail.

All of that is part of the plan.

Throughout this semester, 14 students and four instructors will learn from those failures and discoveries as we run a live experiment of journalism, technology and water studies at the Reed College of Media at West Virginia University.

It’s a class called “StreamLab,” and as we go along, we hope to inform the practice of sensor journalism and also citizen science.

The class is the third of its kind at the Reed College of Media and part of their Innovator-in-Residence program, which brings industry professionals into the classroom to lead a journalism experiment. Recent support from Knight Foundation expands the program over the next two years to embed two innovators per class to widen the network of collaboration and, we hope, accelerate problem-solving for our respective newsrooms and communities.

Earlier projects involved The Wall Street Journal’s Sarah Slobin, who worked with faculty and students on a reporting project for mobile-first delivery, and Derek Willis of The New York Times, who worked with investigative reporting and interactive design students on a data-driven elections reporting project.

Riffle: The open-source water sensor that fits in a bottle. Photo by John Keefe

Data in a bottle

By rights, we should begin with a story and pursue it with tools that might inform that story. Instead, we’re looking for a story that fits our tool. And that is part of the experiment — partly because a semester-long class brings unnatural constraints. But it’s also because we have an opportunity to use a nifty new tool: a water sensor that’s cheap and open-source, and fits neatly inside a water bottle.

It’s called Riffle (Remote Independent Friendly Field-Logger Electronics), and it’s the brainchild of Don Blair, who works with the nonprofit Public Lab (which has also received Knight support) and is currently at the MIT Center for Civic Media.

The key feature, aside from the excellent water-bottle design, is that when it’s sunk in a river or stream, it measures and logs water conductivity, a strong indicator of total dissolved solids. So while Riffle can’t tell us what is in the water, it can tell us that something is in the water. That could be especially interesting for our class if we can detect changes in a stream over time or stark differences at spots along the same stream.

Riffle is still in the early stages, and Blair just started making several of them by hand this summer on the workbenches of MIT’s Responsive Environments Group. (I was lucky to help and learned how to hand-make circuit boards in the process.)

The West Virginia University sensor journalism class is one of the first groups to field-test Riffle, and Blair will join us at the Morgantown, W.V., campus next month to help deploy them.

Sensors in search of a story

Where we’ll deploy these sensors remains an open question.

The area around West Virginia University includes two watersheds, dozens of interesting streams and a long history of contaminated water sources.

Our first few classes have been devoted to conversations with West Virginia water experts, several of whom are also serving as informal advisers. The Water Team – one of four within the class – is tasked with working with these experts to narrow down our site (or, possibly, sites) for sensor placement. And if we find suspicious amounts of solids in the water, they’ll help us figure out what’s up.

Areas of acid runoff from old mines, local wastewater flows and illegal dumping are possibilities the Water Team is pursuing.

Once we pick a site for placing the sensors, the Water Team, led by faculty members Emily Corio and John Temple, will work closely with the Story Team, led by team Innovator-in-Residence David Mistich, to “interview the data.” Students will interview residents, experts, activists, officials and others to report on the issues raised in this project — from what the data can and cannot tell us to the challenges and opportunities of citizen science. We’re collaborating with West Virginia Public Broadcasting and the Charleston Gazette-Mail to produce our story.

Documenting the process

But there’s also a “meta” story — the story of our pursuit of a story. That’s the job of the Document Team, which will track, photograph and report on our progress. When we stumble, they’ll report it. When we make discoveries, they’ll post the results. In near-real time. Their work at streamlab.cc will debut at the Collaborate + Innovate: Lessons from the Challenge Fund session at the Online News Association annual convention on Sept. 24.

We’re also posting all of our plans, lessons, data and the class calendar openly on the StreamLab Github repository. We chose to be an open-source project from Day One. Feel free to follow along as we get wet and learn more about how journalists and citizen-science sensors might work together.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Community Impactarticle ·