How Creative Ownership Structures Can Help Local News Publishers Stay Local

More publishers are trying out public benefit corporations, journalist-owned LLCs and cooperatives to tie publications closer to communities.

For years, American communities have made heroic efforts to save local shops in the face of voracious chain and big-box stores and e-commerce bullies such as Amazon. That’s why you’ve heard calls to “buy local” and “shop local” so much, especially as the COVID-19 pandemic has pushed even more small businesses to close. So it’s a natural extension of that movement for local news publishers to get creative with their ownership structures to stave off buyouts from extractive hedge fund owners, and ask the community to support them as truly local businesses.

That’s the force driving publishers to create journalist-owned companies (Defector, Racket), public benefit corporations (Colorado Sun, Lookout Santa Cruz) and cooperatives (The Devil Strip, Mendocino Voice). And in some towns, local impact investors have even stepped in to purchase important local news outlets (Long Beach Post). In each case, the driving factor for these creative models is to become a sustainable business that will remain locally owned – and stay out of the hands of “vulture capitalists” and hedge funds.

Many smaller community newspapers and websites have done fine as privately owned companies, and there’s been a huge growth in nonprofit news around the country. But these creative models point the way to options that publishers should consider—depending on the amount of resources in their community.

“Whether you have a public benefit corporation or a nonprofit, you’ll have the same headwinds,” said Elizabeth Hansen Shapiro, CEO of the National Trust for Local News. “The ownership structure is secondary to how you find resources where there aren’t any… Some places don’t have a retail base or funder, or philanthropic capability.”

In looking at these various community-minded ownership structures, I learned that each place is different, and there isn’t really a one-size-fits-all model for each local news outlet. Here’s a roundup of those models and how they work for the places they serve.

Local Impact Investors

While many metro daily newspapers have been bought out by billionaires such as Jeff Bezos (Washington Post), John Henry (Boston Globe) and Patrick Soon-Shiong (Los Angeles Times), smaller towns could put their vital news outlets on a stronger path to sustainability with local impact investors. In the case of the Long Beach Post, which started as a blog in 2007, civic-minded businessman John Molina (whose father started Molina Healthcare) used his private equity firm Pacific6 to purchase the publication in 2018.

David Sommers, the publisher of the Post, told me that Pacific6, which is focused on “impact investing” to make a difference in the community, is the sole owner and is being upfront about this with a “Transparency Portal” on the publication’s website. Pacific6 created a holding company, Pacific Community Media LLC (PCM), that acts as an “ethics wall” to make sure Pacific6 investors have no say on editorial matters.

“PCM is the go-between for us and the owners,” said Sommers. “Their day-to-day involvement is around human resources and accounting, giving us resources that would be more expensive for us to do alone. As far as what we cover, they have no say on that… They are very invested in doing projects that no one else would take on. Another project is a historic hotel in downtown Long Beach that was closed for decades, and no one wanted to take on the costs of renovation. There’s a lot of similarities there to journalism.”

Those costs of renovating the Post included going from 3 employees in 2018 to 26 today, all while the rival Press-Telegram newspaper owned by Alden Global Capital has suffered from “death by a thousand cuts,” according to Sommers. The Post has also increased its revenues 10-fold over the past three years, with 8,000 paying donors, despite having no paywall for content. One big success has been the publication’s brand studio for local advertisers, which took off last year during the pandemic.

“One Thursday afternoon the mayor contacted me saying no one knows where to get masks…can you build an e-commerce platform quickly?” Sommers said. “Within 72 hours, we had the platform built, had all the legal guidelines in place, and helped facilitate the sale of 20,000 masks from local vendors – we took no commission or sales.”

But the impact was much larger than that for the Post and its marketing services arm, because it showed they could build e-commerce portals and digitize inventory for local businesses. What the Post thought might bring in $10,000 per month ended up projecting to $1 million in revenues this year. And it all happened so fast that the Post has barely had time to brand and market the in-house agency.

While Molina and Pacific6 could sell the Long Beach Post to anyone, including a hedge fund, one of the biggest benefits of having local impact investors is that they care more about community impact than immediate financial returns.

Public Benefit Corporation

Another option for local news outlets is the public benefit corporation (PBC), which is a for-profit company that also serves a larger mission in the community. A PBC has higher standards of accountability and transparency, not just for shareholders (PBCs can go public too), but for the community. At the moment, 30 states allow for the creation of a public benefit corporation, and there’s also B Corp. certification, which has an additional cost and audit, and is available in all states. Notable B Corps include the Guardian, Kickstarter and Patagonia.

In local news, the startup Lookout Santa Cruz is a recent addition to the PBC landscape, led by longtime journalism analyst Ken Doctor. Doctor told me he had multiple reasons to go with a public benefit corporation, including the chance to get capital from impact investors, the desire to be part of the business community in Santa Cruz – and the chance to make political endorsements (something not possible with nonprofits).

“My whole model aims to prove that earned revenue can support a large replacement news organization, one that becomes the primary news source for a community, replacing flagging or suicidal dailies,” Doctor said. Lookout, when fully staffed this fall, will employ 14 full-timers, eleven of them in the newsroom, for a county of 276,000. “We need both reader revenues, and ads, and if you ask for ads, it’s harder to ask for support as a nonprofit than to offer effective value as a business transaction. Certainly, you can get support as a nonprofit, but if you want enough revenue to run a primary news organization, you want to be a member of both the business community and the civic community, joining the business councils and chamber as well.”

Lookout is currently privately owned, with funding from impact investors who aren’t motivated by the Silicon Valley “hockey stick” types of returns, but basic sustainability and service to the community. It follows in the footsteps of the Zebras Unite movement, which aims to “catalyze the community, capital and culture for people building businesses that are better for the world.”

Another prominent public benefit corporation in local news is the Colorado Sun. Born out of the chaos that engulfed the Denver Post in 2018, it was initially funded by the failed Civil blockchain experiment. Unlike Lookout Santa Cruz, the Sun is owned equally by its founding journalists. Larry Ryckman, a founder and editor of the Sun, told me that they haven’t closed the door on becoming a nonprofit, but the public benefit corporation allowed them to move more quickly.

“There’s a lot to admire about nonprofits, there are plenty of worthy ones,” Ryckman said. “But for us, we felt the public benefit corporation allowed us to be more nimble than if we were a nonprofit. Even as a nonprofit you need to make money. We treated it as a business, and couldn’t have our expenses get ahead of our revenues.”

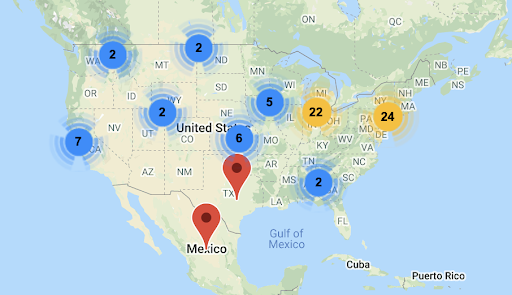

Ryckman said that the founders have a clear vision of what the Sun is, and if they want to launch a new podcast or newsletter they can do that quickly and truly embrace the spirit of a startup. That nimble spirit will be tested severely, as the Sun will soon be running 24 community newspapers in Colorado bought out by the National Trust for Local News, the Sun and a coalition of impact investors. The new Colorado News Conservancy is a public benefit corporation, created especially to make it nearly impossible for the papers to be bought by a hedge fund.

“Our approach in Colorado is that.. the ownership structure needs to match the business model of the organization and the resources that are available to it,” said Hansen Shapiro of the National Trust for Local News. “In the case of the Colorado papers, these were profitable papers. The funders we could bring to the table matched for a public benefit structure. What it allowed us to do in Colorado and elsewhere is share ownership with local investors. In a PBC, we can have special shares that guarantee it won’t be sold to bad actors. That’s a pretty powerful check against papers in the future being sold to bad actors that don’t have the public’s interest at heart.”

Journalist-Owned LLC

No matter the ownership structure, there’s been a rising ethos of journalists controlling the levers of power. And recently, more news outlets have taken a journalist-owned for-profit approach, with Defector Media (folks who left sports blog Deadspin) and Racket (former editors at alt-weekly City Pages in Minneapolis/St. Paul).

While the journalist-owned Colorado Sun is a public benefit corporation, the journalist-owned Defector and Racket are LLCs. But in each case, there’s a freedom of being in charge and not getting beat down by corporate heavy-handedness.

“I can safely say that being one of lots of owner/operators definitely lacks the kind of fun-filled worker oppression we all imagined would come with being moguls. No mass layoffs over the phone, no changing the locks overnight, no salary or benefit cuts, no agitating against union organizers,” wrote Defector’s Ray Ratto in a special look back after a year at the Defector. “Mostly, though, I am learning how to have what passes for the time of my life. I work for and with smart people who don’t spend all day every day trying to prove it, and knowing that we’re all in it together all the way down to the paycheck provides a level of satisfaction that no other job ever has.”

Another thing these publications have in common is how closely tied to their communities they become when relying so much on subscriptions, memberships and donations. Racket’s business model is subscriptions, with readers getting a “high number” of stories before hitting an eventual paywall, according to co-founder Jessica Armbruster. She told me that they were inspired by the folks at Defector Media, and hired the same web development firm, Alley, to help get it off the ground. Alley didn’t take an upfront fee, but instead gets paid a cut of revenues generated.

“We got really lucky getting Alley to help us with building our website,” she said. “They really helped with the legwork… The stars have aligned and the journalism part comes naturally.”

Having Alley taking care of the back end, including setting up subscription payments, means that the editors and writers can focus on editorial and serving their audience with typical news, arts and entertainment fare you would expect in an alt-weekly. “The dailies have their purpose, but there also needs to be space for alternative voices, for humor, and we each have our tone on what we cover and a readership,” Armbruster said.

Their motto? No bosses, some bias.

Cooperative

And for those news outlets that really want to create a democratic process for ownership, there’s the cooperative model. This includes worker-owned co-ops and reader-owned co-ops and multi-stakeholder co-ops where employees and readers own it.

Cooperatives are typically for-profit companies, and they have by-laws to govern how decisions are made, with input from the members. Most people have interacted with this model at grocery co-ops or utility co-ops in America. But news co-ops have an interesting history, including at the Greenbelt (Md.) News & Review, a volunteer venture started in a “New Deal Green Town” in 1937.

More recent examples include the reader co-op at The Devil Strip in Akron, Ohio, and the multi-stakeholder co-op being created at the Mendocino Voice in California. Readers buying into co-ops might be able to have a voice in some matters, but not all of them. And they won’t typically get a dividend like members at REI, according to Olivia Henry, a journalist and graduate student at University of California, Davis, who convened a News Co-op Study Group this year to discuss the model.

“When you are a member-owner of a news co-op, you find you have a different role in the organization,” Henry said. “You can’t call a journalist and say you want a story covered. You can vote for a board, and get economic benefits, discounts or access to sales. You vote on the bylaws. Normal owner-members have very limited say and no editorial power at The Devil Strip… An ownership stake is different than a subscription or a donation. It’s very different than equity. You’re putting money there that you might not be able to take back.”

I was part of the News Co-op Study Group and enjoyed the speakers and discussions that it spawned. Henry and I both thought that the “shared services” model for co-ops had a lot of promise for local news. It’s similar to the Associated Press, where you pay to be a member, the members are also the owners, and they receive a service that’s helpful for the news organization – in this case, news wire stories, photos and videos.

An example of a local news shared-services cooperative is CoastAlaska, with seven public radio stations banding together to create an umbrella organization that runs all the back end and financial work. The editorial at each station is independent. There are some other nascent shared-services co-ops being built in Cleveland and San Francisco, and as a New Mexico-based consultant who works with small newsrooms that lack similar services, I’m curious to find out if this could work here.

In the end, decisions about ownership structures will depend on what feels right for each local news organization and the type of support it might receive from the community. For those places with high-minded impact investors, a locally-owned LLC might work. For towns with strong small business communities, a public benefit corporation could be a good fit. For news outlets started by refugees of shuttered or “ghost newspapers,” a journalist-owned LLC could be worth a look. And for those folks who want a very decentralized and democratic process, the cooperative would fit.

In any of those cases, the important part is making sure news outlets stay tied closely to communities and don’t become fodder for the next hedge fund takeover.

Mark Glaser is a consultant and advisor with a focus on supporting local and independent news in America. He was the founder and executive director of MediaShift.org, and is an associate at Dot Connector Studio, and innovation consultant at the New Mexico Local News Fund.

Image (top) by Rosemary Ketchum at Pexels.