Huffington Post Features Janet Echelman, Dilworth Plaza Artist

By Melissa Henry, Janet Echelman, Inc

Artist Janet Echelman, who designed the public artwork for Philadelphia’s Dilworth Plaza recently shared her words for a feature on the The Huffington Post. Echelman’s TED Talk and accompanying article headlined their curated TED Weekend program themed “Imagination Innovation.” A Knight Arts Challenge Grant is helping to construct Echelman’s artwork under the leadership of Center City District, as part of the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation’s $9 million initiative funding innovative projects that engage and enrich Philadelphia’s communities.

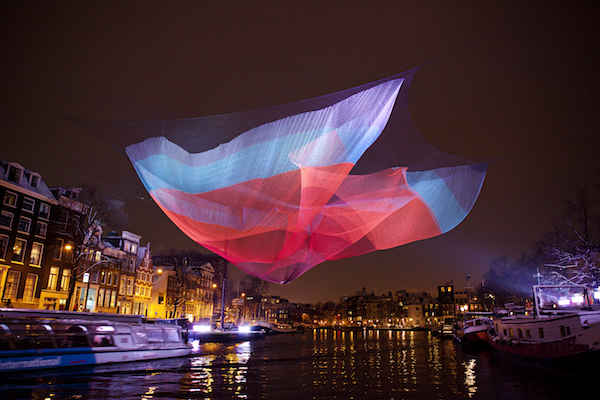

This winter, Echelman’s artwork was installed over the water in Amsterdam in front of its Opera House. Here is the timelapse video of the installation. The artist shares the challenges she was faced with in her journey to achieve her dreams and how she overcame them to turn imagination into reality. Article below.

7 op-ed writers addressed Echelman’s work and its impact:

- The Rigor of Creativity, by Thomas Fisher, professor and dean of the College of Design at the University of Minnesota

- Marrying Art and Science in the Public Square, by John M. Eger

- Art Inspires! Broadening Art Appeal, by Sylvie Leotin

- Thinking Inside the Box, by Nicole Glassman

- Fiber Arts Shine as Public Art, by Hilary Harkness

- The Arts and Our Kids: An Essential Element for Success, by Gwenn Schurgin O’Keeffe, MD

- Imagining Music in Physical Form, by Richard Olcott

One of the most gratifying results of my TED talk has been to see volunteers translate it into 33 languages—from Armenian and Arabic to Turkish and Vietnamese — and receive comments from people around the world about how my story is affecting their lives.

I heard from Pedro Perea in Madrid, a volunteer at a juvenile prison who brings translated TED talks to teenage inmates:

“They usually give up when confronting difficulties. But when your talk ended, they applauded, which means more than they just liked it: you can see a new energy in their faces, the energy of ‘I can also do difficult things’. Their usual excuses for not trying to change themselves started to disappear … they saw that persevering brings results.”

I was stunned. I could never have imagined my story traveling across oceans and languages to reach this audience, translating to different circumstances, my story of being rejected by art schools yet going on to become an artist on my own.

There’s just one thing I’d like to clarify. It sounds like I’m railing against the Establishment, and their mistake of rejecting me.

But here’s the thing– I don’t think they were wrong.

My works at that time were still unformed. It took ten more years before I found my voice as a sculptor, and another ten years before I figured out how to build my sculpture at the scale of buildings. Now, I’m working hard at the next challenge, to make sculpture gestures at the scale of the city.

When I started, my biggest challenge was learning to hear my inner voice– finding a way to be quiet enough to notice and pay attention to my own ideas. I began writing and drawing with both my dominant and non-dominant hands. Somehow the non-dominant hand gave me access to ideas that would not have come to light, overpowered by my more conscious, skilled hand.

Once I began to hear and pay attention to my fledgling ideas, the biggest hurdle was to learn how to respect them. That was hard, because the way to respect an idea is to invest the attention and work needed to develop it.

When developing an idea, I remind myself not to start with compromise. I envision the ideal manifestation of the idea, as if I had no limits in resources, materials, or permission. I’ve learned there’s a cost to eliminating options too soon, as some might be more viable than they initially appear. For my sculpture She Changes in Porto, Portugal, I was originally prohibited from going over the street due to regulations, but my vision for the work required it to “float” above the roundabout. I decided to show both versions– what I envisioned, and one according to the rules. Turns out my images were compelling enough for them to obtain a variance.

In early design phases, I try to give my “inner critic” a hall pass to get lost for a while, and that goes for external critics as well. When ideas are young and vulnerable, criticism can be lethal.

I try to imagine my goal as a reality, and then work backwards to figure out all the steps I need to take to make it so. I look to the examples of people who accomplished unimaginable changes. Sometimes, I imagine how Gandhi must have felt as he set off on the Salt March, somehow believing that one man’s footsteps could begin to change nations. He was able to hold the final vision in his mind, and understand each step needed to make it reality. We all have the potential to do that, but it’s a skill that takes practice.

My dream is to create spaces which foster calm and contemplation, to transform hard-edged cities with billowing softness. How can I create this kind of change with something like sculpture, and how can I do it at the scale needed to hold its own city? This is what pushes me to “engineer a new art.”

In my TED talk “Taking Imagination Seriously,” I shared the hurdles I had to overcome to bring my billowing sculptures to the scale of buildings, and my dream of bringing them to the larger scale of the city. As I walked off the TED stage, the CEO and CTO of a leading design-software company, Autodesk, offered to help make that dream a reality, and we’ve been working these past months on a new tool that is enabling me to do just that, in a place with great meaning to me … and I’m looking forward to announcing the project early next year.

Now, I’m actually creating the art I imagined for cities. I write this from Amsterdam where this week we premiered a sculpture suspended from City Hall over their historic Amstel River. We’re now constructing the mist and light sculpture described in my TED talk for the plaza in front of Philadelphia City Hall, and developing projects for cities around the globe.

It’s been a surprise that the work is still so hard. Perhaps that’s because as soon as we figure something out, I push the boundary further, encountering new challenges yet again. Often, the struggle is to figure out what my next step should be, then finding all the little parts that must fit together in order to achieve that next step. I’m still constantly learning, pushing, and dreaming, and it never gets easy. But that’s what keeps it fresh.

I recognize that it is through the engagement with my craft– by recognizing an idea and drawing it out, building physical models, collaborating with experts, constructing the sculptures at urban scale, and maintaining them through years of weather and interaction with the public– that a new art for cities has become real.

So as the year 2012 draws to a close, I recall the words of Picasso for my New Years Resolution:

“When Inspiration finds me, she will find me at work.”

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·