‘Life between the shelves’: Reimagining libraries as civic spaces

This post is third in a series about a gathering of library directors Knight Foundation convened in Miami Feb. 11-12, 2017, as part of its continuing work with libraries. Knight Foundation also recently released a report “Developing Clarity: Innovating in Library Systems,” and announced a package of funding to support innovation in libraries.

Brian Bannon opened with a succinct and pointed question:

“How many people have done library renovation in the last five years?” he asked. “And in the last two years?”

As hands shot up on the afternoon of the second day of Knight Foundation’s library directors’ meeting, on Feb. 12, the mini-panel “Libraries as a Civic Space” got off to a fast start, with Bannon, commissioner and CEO of the Chicago Public Library, and Marie Ostergaard, head of community engagement, partnerships and communication for Dokk1 in Aarhus, Denmark.

“That’s a lot of people,” Bannon said, looking out over the group of 40 directors. “How many people have one coming up on some level in the next two years?”

Most of the remaining attendees put up a hand.

“It’s like repainting the Golden Gate Bridge,” Bannon said. “It seems like you’re always probably renovating it, if you have enough branches out there.”

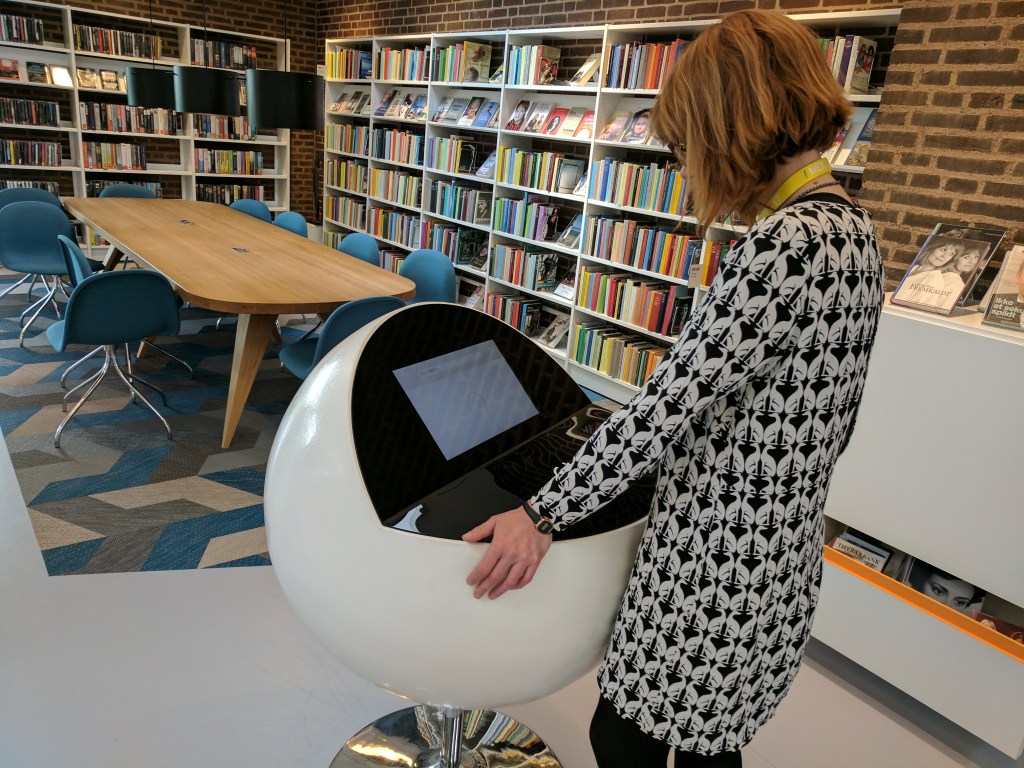

Ostergaard then offered a how-to slide show in which she talked about the Aarhus Public Libraries’ development of the physical library of the future, Dokk1.

“Dokk1 is our new main library in Aarhus,” Ostergaard said. “Aarhus is the second-largest city in Denmark, which is not saying a lot. It’s about 300,000 people. We built a new library. We started the process in 2005 and we opened in 2015. We went from a library where we had something like 35,000 public square feet into somewhere where we have 150,000 public square feet. All in all, the building is 300,000 square feet. The rest is rented out to companies, so we live together with someone else. That was our choice.”

The library as a public square

Ostergaard said the library worked with community groups and civic leaders to define the needs for the new building, while holding out for the “last responsible moment,” acquiring input from the community and delaying decisions until they had to commit. She added that the entire process was driven by library leaders and the community instead of the architects.

“We decided which kind of processes that we wanted the architects to engage in. The result that you see is from 10 years of process, while we’ve been doing a lot of development work on the site, testing a lot of stuff on the site [and] in the old library. We were brilliantly clever in this because we were clever enough to know that we didn’t know anything, that we needed to involve everybody in the community to get the result that we have.”

Ostergaard said daily traffic to the library has more than doubled from the old library to the new, from about 1,800 patrons per day to 4,000.

“And people stay longer,” she said. “We have people come in at 8 in the morning and leave at 6 in the afternoon. We’ve got a whole new part of the population coming into the libraries than we did before. Our intention was to not create a book repository, but a place for people.”

One of the primary goals of Dokk1 was to establish itself as a cultural hub for the city of Aarhus, she said.

“This is the only place you meet across gender and age in a non-commercial space. It’s a library. You do it outside on the squares, as well, in the city squares. We tried to deal with the library space as a square. We’re talking about a life between the shelves, life between the buildings. We created little oases between them to have stuff happen.”

Moderator Ryan Jacoby, founder of MACHINE, a New York-based strategy and innovation company, asked Ostergaard if experimentation with services is part of Dokk1’s DNA.

“One of the things we actually program some of this program space for is testing out new stuff,” she said. “We have what we call a transformation lab. We did that at the old library, too, where we would test our old and new ideas for new services. Furniture in the new library was tested in the old library with users, so that they could give input. We have places where we try to test everything that we do before we implement it.

Building for 100 years

The idea was to build flexibility into the new building, she added. “We built for 100 years. Everything needs to be able to change place. Whenever we change something, if it doesn’t work, we go through a process of discovery. And human design thinking, whatever you call it, we test out, we tweak the spaces a little, see what happens….”

Bannon lauded the idea, and said that Chicago Public Library, which has a partnership with Dokk1, also can benefit from the lessons learned during the development of Dokk1. “All the years that you spent working to come up with this concept, I think there’s something actually really radical and simple about it, which is you spent these 10 [years] designing for very flexible space that will constantly be evolving, and designing for that as opposed to designing for fixed space.

“For us, in Chicago,” he said, “we don’t need to spend 10 years designing, because you’ve already done that for us. But I think that the marker of what, to me, has been so successful when I visited your arguably less architecturally interesting former central library is that it always felt like it was changing. When I saw Marie give this presentation before,” he told the directors, “the grand staircase could be a makerspace one minute; it can be a musical performance the next, or a group of people studying. That really simple idea is a pretty profound one for us to be thinking about as we look at civic architecture and design.

“In Chicago, our history has been something called prototypes. The idea of a prototype, for those of you who aren’t familiar, is that it’s libraries at schools, it’s firehouses. There’s a long-standing tradition that civic architecture—which is funny in a city like Chicago that’s known for architecture—is predominantly downtown buildings. [But] I think that we’re in this moment now where we’re thinking a lot about neighborhoods. We’re thinking a lot about how we bring our communities together.

“And regardless of how the program is spaced in, the importance of creating a beautiful space, a space that people can connect with, that resonates for them, to me is No. 1 of the most important things we should be thinking about doing. It sends a message to a neighborhood that this neighborhood matters. What better message to send than creating a beautiful piece of architecture that resonates for people?”

Bob Andelman is a Florida-based freelance journalist and author. For more, visit andelman.com.

r

-

Communities and National Initiatives / Article

-

Communities and National Initiatives / Article

-

Communities and National Initiatives / Article

-

Information and Society / Report

-

Technology / Press Release

-

Journalism / Article

-

Communities and National Initiatives / Article

-

Communities and National Initiatives / Article

-

Communities and National Initiatives / Article

-

Technology / Article

Recent Content

-

Communities and National Initiativesarticle ·

-

Communities and National Initiativesarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·