If buildings could talk, this is what they’d say

Photo: The Miami Center for Architecture and Design. Photo by Francisco Javier Moraga Escalona.

Walking up to the magnificent historic edifice that houses the Miami Center for Architecture and Design, you can hear a voice describing a notable building in downtown Miami. The steps of this former U.S. post office, which was constructed in 1912, almost serve as a mini-amphitheater. Surrounded by the city life flowing by, you could sit and linger, taking in the histories of this city’s early architecture, without going any further.

But then you would miss the rest of “Listen to this Building,” a truly compelling art and architecture exhibit that is geared toward the blind, but accessible to all.

It’s a project from Knight Arts Challenge winner Exile Books, in conjunction with the museum and the Miami Lighthouse for the Blind. Inside, there are tactile relief works of 10 architecturally significant Miami buildings, a large model of the host building that can be explored by touching its details, and a braille book that includes a CD of the audio outside.

“If buildings had a voice, what would they say?” Exile’s founder, Amanda Keeley, asks in reference to the kernel that sparked this unique exhibition.

The directors at the Miami Center for Architecture and Design (also a Knight Arts Challenge winner) first approached Exile Books with a vague idea for a show about architecture that was “a little more experimental and nontraditional.” The concept of telling the stories of historical structures in a manner that didn’t involve visuals emerged.

According to Ricardo Mor, operations and programs coordinator at the Miami Center for Architecture and Design, organizers didn’t want typical photographs of buildings hanging on the wall. What if visitors had to listen, and touch, to understand the histories? What if they couldn’t actually see the architecture? The exhibit took form from there. In a nice happenstance, the timing of “Listen to this Building” would coincide with the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

It seemed natural that an acoustic element should make the introduction, “triggering the experience” from the outset, Keeley says. So she invited a number of people to read texts, in different accents that underscore Miami’s diversity. But even the descriptions are not focused on visuals. For instance, the stunning Gesù Church down the street is painted an eye-catching shade of salmon; however, in the audio and braille descriptions, the word “pink” would not necessarily be used. For those with sight, the color of the church is certainly one of its more defining elements; for those without, the arches, trimming and stairs might be more informative.

Other buildings referenced in this “listening” tour include the Alfred I. Dupont building, Olympia Theater and Freedom Tower.

Tactile relief of the U.S. Post Office/MCAD building. Photo by Irvans Augustine.

“Listen to this Building” is designed for the visually impaired, and to make all visitors explore new modes of understanding our aesthetic surroundings. But it is also visually beautiful for those of us lucky enough to see.

On the walls hang what look like drawings of the 10 historical buildings highlighted in the exhibition. They resemble wood cuts, with raised lines for those only experiencing them through touch, but they also look like simple and clean blueprints. The tactile reliefs, without color, make you study the physical designs more than you might if these buildings were presented only as photographs hanging in a gallery.

Visitors can explore the historic building by putting their hands through small windows and feeling the architecture. Photo by Irvans Augustine.

In the middle of the exhibition space stands the 3-D replica of the old post office building, created by Matthew Wasala and Patricia Elso, two students at Florida International University’s College of Architecture and The Arts. Through small windows, you reach your hand into the building, feeling the details and design of the stairs, the intricate façade, the interior.

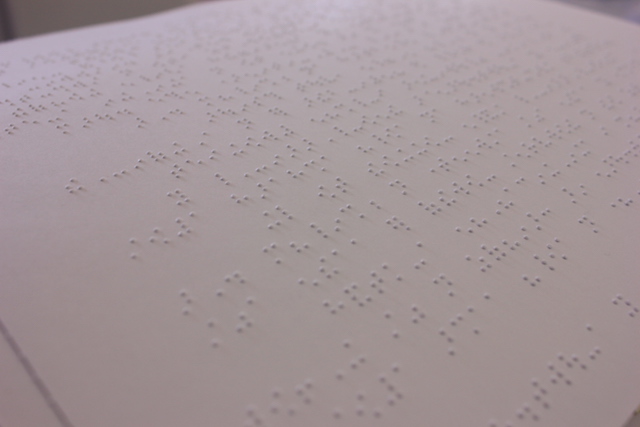

Then, there is a limited-edition braille book about all these structures–which, of course, contains no images or printed text. Its all-white coloring and delicate, raised braille imprints make it a stand-alone, luscious piece of artwork, even if the blind can’t see it and the non-blind can’t read it.

The beautiful all-white design of the braille book is an art piece in itself. Photo by Irvans Augustine.

On the opening day during DWNTWN Art Days in early September, volunteers from the Miami Lighthouse for the Blind led visitors with sight through the exhibit, and through the architecture of the building, while blindfolded. Going up the staircase (a design gem all its own) while sightless was a disorienting experience, as this writer can attest, and made this art opening what its curators had hoped for: a way of “viewing” art and design in the most unconventional fashion.

As far as Keeley knows, this is a one-of-a-kind exhibit, and one that might be replicated elsewhere. Its combination of art with a love of books and history, centered around a population that might have been left out of traditional venues for such expression before, certainly is unique for Miami. “Listen to this Building” found a way to reveal the physicality of place by activating all the senses. Think you can’t “see” an architectural masterpiece? Think again.

“Listen to this Building” runs through Oct. 17 at Miami Center for Architecture and Design.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·