Looking through other people’s things at St. Paul’s College of Visual Arts

The College of Visual Arts has a small gallery space, but really makes the most of it. Situated in the middle of the vibrant Selby/Dale area of St. Paul’s Cathedral Hill neighborhood, in addition to its main exhibition galleries inside the building, the college capitalizes on its corner location and brisk foot traffic by offering “Portals on Western,” a rotation of mini-exhibits for public view in the gallery’s street-side windows and generous storefront display cases.

The most recent “Portals on Western” exhibit, “Inhabitants in a Parallel Universe” by Juana Berrio, is the most astute and thought provoking of the shows I’ve seen in that space since the college began its public art exhibition series two years ago.

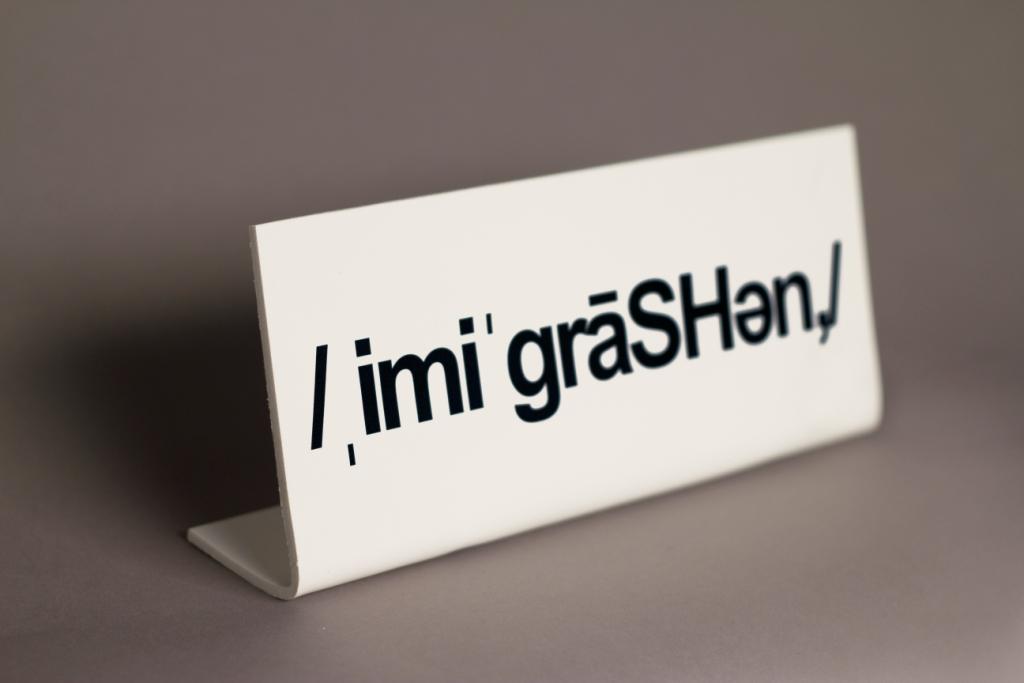

Berrio borrows from the display conventions and didactic language of natural history museums to present two contemporary immigration stories. All we’re told is that both individuals are American citizens whose families migrated to the U.S. in the last 100 years in the wake of crisis in their native countries; one person’s family immigrated from Europe, and the other has ancestral roots in Africa.

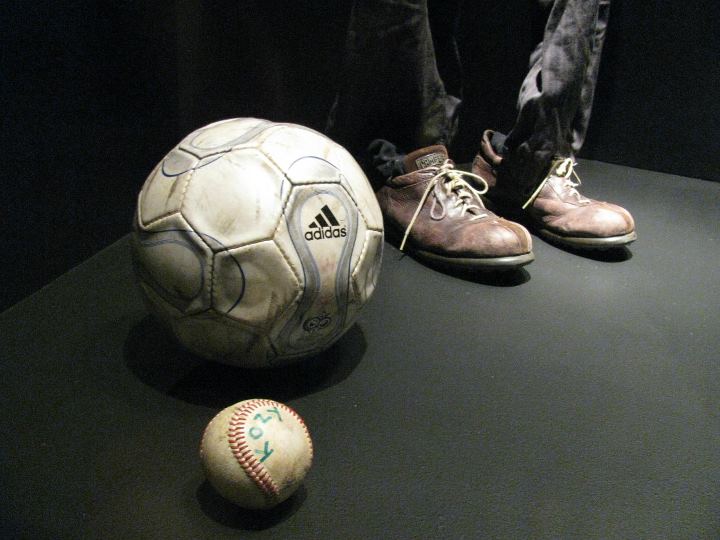

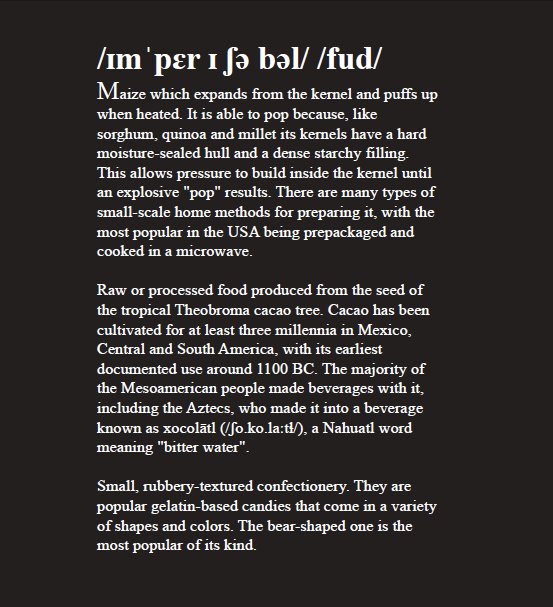

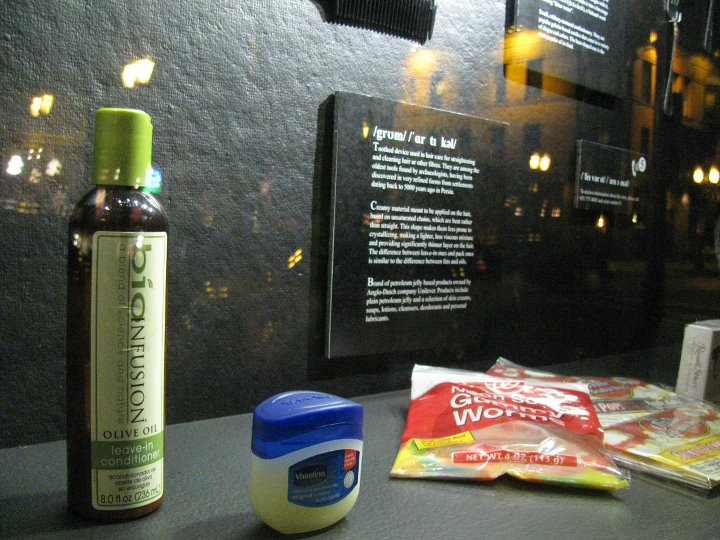

The visitor is left to piece together a narrative of sorts for each of these contemporary people, by way of an arbitrary collection of everyday objects and ephemera from their (and our) daily lives: razors and shaving cream, convenience food and dry goods, clothing and sports equipment, tsotchkes and mementos. All are neatly mounted and displayed in the gallery’s hermetically sealed window cases, meticulously annotated by the kind of abstruse text and phone-accessible didactics that will be familiar to anyone who’s visited a museum. But even with all these auxiliary “educational” materials, no framing story is given at all; individual artifacts aren’t tied to a specific owner. In the absence of such context, their stories are impenetrable, ridiculous even.

Berrio’s playful exercise in visual storytelling is open-ended but instructive, highlighting the absurdity of attempting to conjure a meaningful life story from a bare handful of unmoored objects. And by omitting the framing stories that would provide these artifacts that crucial context, Berrio calls attention to the absolute power of the invisible, curatorial hand in shaping such object-based narratives in natural history museums.

I remember visiting the Panhandle Plains Historical Museum near my childhood hometown in West Texas. Among the dinosaur bones and geodes, past the giant windmill, a shrine to the oil industry and a mocked-up “Pioneer Town,” was the anthropological section of the museum, filled with archeological artifacts and idealized dioramas depicting life among people indigenous to the region — Native Americans and also pre-historic hunter/gatherers. Next to the dioramas, pinned up for display in glass cases were objects ostensibly representative of everyday life for the “People of the Plains:” cradleboards, ceremonial textiles and beadwork, cooking utensils, an array of arrowheads, pottery shards. My favorite was the life-size teepee, kitted out with pleasantly rustic-looking sleeping areas and a flickering “fire,” where a family of unspecified native heritage was caught in medias res, as if settling down to unwind for the evening.

As a kid, I found the “scientific” evidence of the artifacts side by side with the life-like set piece utterly persuasive; and even though I know now it was imaginary, drawn from whole cloth, really — just a neatly limned, accessible story so visitors could relate to what they were seeing in the cases — I can’t help but wonder to what extent, even as an adult, that little family scene in the museum’s “teepee” colors my conception of how “real Native Americans” lived.

Berrio’s cunning send-up to such familiar anthropological tellings of “others’” narratives is plainly executed but remarkably effective; she highlights both the voyeuristic appeal and inescapably pernicious shorthand inherent in them. From the show summary: “Their belongings are not labeled or titled. All you can read are descriptions of things you may or may not know. What you see is what you choose to see.”

“Juana Berrio: Inhabitants in a Parallel Universe” is on view 24 hours a day, seven days a week in the display and storefront windows of College of Visual Arts gallery through Jan. 6, 2012; 173 Western Ave. N. (on the corner of Western and Selby Avenues), St. Paul, 55102.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·