Notes from the Everglades: An AIRIE report

By Brenna Dixon, AIRIE

I grew up a born-and-raised Floridian, knowing that if it was raining in the front yard, probably my brother and I could play in the back where it would be sunny. I watched half-eaten possums float by in the canal I fished with a childhood friend, was mesmerized by the seemingly endless saw grass that stretched beyond our car windows, and claimed the purple gallinule as my favorite bird when I was seven.

In college I kayaked the Hillsborough River while alligators slid around me. I drove an old boyfriend out to Lettuce Lake Park and pointed out roseate spoonbills and limpkins and wizened wood storks. Once, my friend found a baby python on campus and kept it until it died of some mysterious snake-baby illness. After I graduated and moved away, some freshman boys got caught keeping an alligator under their bunked dorm room beds. To this day I tell people, “I come from a place where nature has teeth.”

This is the Florida I write about in Iowa, where grad school took me and teaching keeps me. This is the Florida I am proud to come from. It is the Florida I love. I came into my residency here at the park wanting to sink myself into the Glades I grew up alongside, to get to know the ecosystem I’ve always known around the edges more intimately. I wanted to understand it from the inside, up close, but I wanted also to see the ecosystem as a cohesive whole, to understand it the way I do from an airplane window: ocean, suburban sprawl, saw grass—gradient and huge, subject to invasions of men, sugar cane, and all kinds of biota.

I think about the idea of invasion often. The question of it infuses itself into my fiction. I wonder about ecological invasions. I wonder about invasions of the body—cancers, illnesses, microscopic things that crawl through veins. Invasion is defined as an unwelcome intrusion, an incursion of great numbers. But I’m constantly left wondering about the point at which an invader becomes a normalized part of a system. When do we stop fighting and embrace the invader, or at least learn to live with it? What, ecologically, is our responsibility as human beings?

On my second day here I lucked into sitting in on an invasive species briefing where I met Jonathan Taylor, Bryan Falk, and Michelle McEachern, all of whom have been kind enough to share their time with me. Last week, Jonathan walked me through the year-old growth of a restoration area and gamely addressed my tipping-point question, suggesting that as people, aware of our impact, we should be careful with how we move species around. (My apologies to Jonathan if I’ve paraphrased his ideas in a way that misconstrues them.) In a similar conversation with Skip Snow on the Anhinga Trail, Skip said he wondered if and when the python would become a Florida mascot like the alligator. What would the cultural impacts be? Would a high school kid be forced to dance around in a stuffy python costume at pep rallies? Would people come to the Everglades to see the snakes? Already there’s a python next to the gator on the wildlife rehab’s billboard down the road.

During my third week, I watched Bryan Falk necropsy a python brought in by Tom Rahill of the Swamp Apes. Tom names each of the pythons he and his crew of veterans catches. This is a practice I appreciate and admire. The Swamp Apes acknowledge the life of each python even though they aren’t supposed to be here. During this rainy season, I can’t help but liken them to the World Meteorological Organization naming tropical storms. Pythons and hurricanes—each coming into a landscape and changing it.

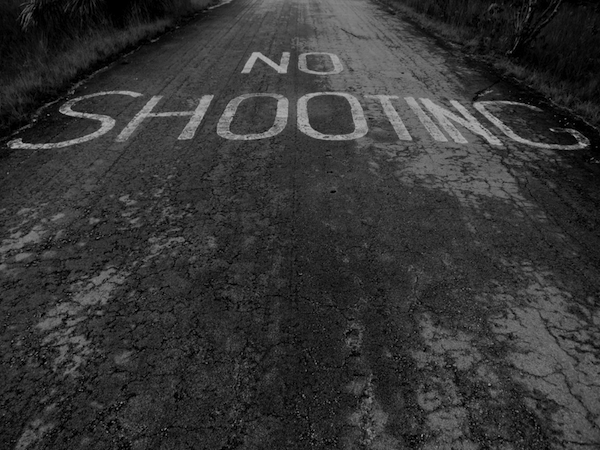

The next night I hopped in Tom’s car and road-cruised Chekika for live pythons. We shot the roads under a full honey moon and I though about the bendy-straw texture of a python’s trachea. I knew that if we found a python, I would see the reptile itself—its beautiful patterned brown-and-beige—but I’d also think of the mesh of its lungs, red and breathing. I’d think about the flat fat bubbles lining the animal and wonder how much plasma is built up in the lower body. I’d think about it from the inside and the outside, the same way I’ve come to think about the Everglades itself.

In the end, a body defeats an illness, adapts to it, or dies. The Everglades is a body unto itself. Some invasives it will defeat. Some it will adapt to. But this salty-swampy-grassy-woodsy secretive ecosystem seems built upon resilience. It will survive. Of course it will survive. And for my remaining few days here I will walk trails and watch the rain and make note of rising water levels. I will watch a new season begin.

View Brenna’s Everglades photo blog here.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·