Open rehearsal for New World Performance Laboratory’s “The Devil’s Milk Trilogy” generated good audience feeback

A few months ago, CATAC (the Center for Applied Theatre and Culture) announced that it had received a $15,000 grant from the Knight Foundation to create a dramatic piece about the history of rubber in Akron through its production arm, the New World Performance Laboratory.

The outlines of the project were covered in another post, in which director James Slowiak explained the potential structure of the three-part work, called “The Devil’s Milk Trilogy.” Part I is a one-man show covering the bloody, exploitative and cruel history of the beginnings of the industry. That’s followed by a musical comedy section, and it ends with a collage of notable rubber and tire figures prominent in Akron’s story with the industry.

As reported earlier, the group worked with primary text sources (John Tully’s “The Devil’s Milk,” the diaries of Roger Casement, Vicki Baum’s “The Weeping Wood” and W. E. Hardenburg’s “The Putumayo: The Devil’s Paradise”) and, through the miracle of dramaturgy, they’ve begun to compose the story in dramatic terms.

The creative process involves a series of three intensive, two-week work sessions, followed by open rehearsals where the public can come, look at the progress made thus far on the drama, and share comments and feedback. It’s a great way to get the community involved in a theatrical process, but also a good educative device to see the complicated thinking that goes into making a play.

On the weekend of March 20-21, Part I, “Death of a Man,” was presented for an invited audience (there will be another open rehearsal in May).

Drawing from a wealth of materials about the beginnings of rubber harvesting in Africa and Central and South America, Slowiak and actor/project manager Jairo Cuesta decided to focus on the experience in the jungles of the Amazon as a means to evoke the story of countless indigenous men, women and children who were exploited, mutilated, sold into sexual slavery and massacred–all as the result of what writers call the mad search for natural rubber.

The set for “Death of a Man” is used to convey not only ambiance but also pertinent symbols. Currently set up as a series of five landscapes, portions of the large stage have areas where solo performer Cuesta can transition from the Storyteller to the Man from the Putumayo, to one of the Blancos in La Chorrera, to the lone figure of The Remembering, and finally depict the Death of the Man.

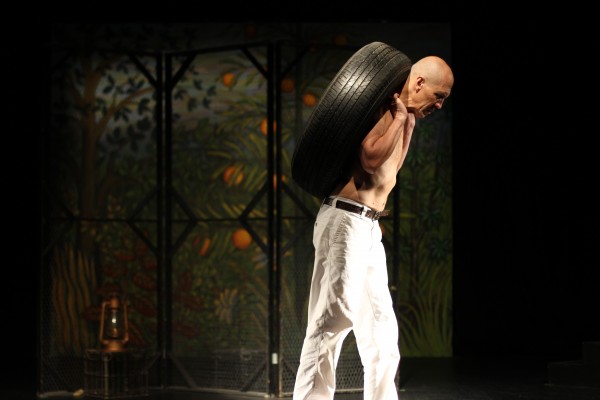

Jairo Cuesta in “Death of a Man.” Photo by Brian Dotin

To establish mood, a painted screen upstage and a multicolor hammock depict the rich foliage and lush nature of the tropics. Surrounding the stage is a two-foot wall that is painted to look like a long jungle snake (a good means to get at the danger of being in this area, as well as a symbol of having the civilization choked to death and swallowed). Center stage is a screen that hides what may be behind it, but there is a very telling whip hanging from the wall. Against the screen mid-stage is a tilted car tire (a symbol of the industry, the need for rubber, and the reason for exploitation). Downstage is a stark tree and a set of chairs and stools that serve as a stockade and represent the cruel punishment that indigenous people went through to keep production levels up.

Jairo Cuesta in “Death of a Man.” Photo by Brian Dotin

Actor Cuesta wanders through these various landscapes reprising the story of an entire civilization. As the Storyteller (which is an honored traditional role in a community based on oral tradition), Cuesta whirls through the area doing a creation dance and singing, setting the mood for a people close to nature who have a reverence for story and song as art. Later he moves to the stockade and miserably outlines his central character’s life – basically that it is very painfully ending, as it has for most of his people, including a young son who was dismembered at the hands of the exploiters. Upstage he carries the burden of his tribe by toting the tire on his back, revealing in this gesture the weight and burden of the rubber trade and industry on his people.

Jairo Cuesta in “Death of a Man.” Photo by Brian Dotin

In all, it is a grimly dark tale, one that had the invited audience paying close attention and watching everything (as many said later) so that they could take it all in and figure out what was going on. Almost everyone got that Cuesta was switching characters – and understood who the new character was after a few seconds. Everyone agreed at this rehearsal that Cuesta is a strong physical actor who has command of variations of tone to change character easily. He seems ready to go with the production when it is presented in full in early 2016.

Most comments brought up by the audience had to do with the set. As one might expect, what someone particularly liked did not sit so well with another. One person thought the tire center stage was too omnipresent, while others thought that was the point – the industry and what it wanted was a giant in these peoples’ world, and ever in their faces.

One person saw the three sides of the two-foot wall as a kind of European circus, where acts changed places, allowing the audience’s eye to follow and know that yet something more is vying for attention. The Blanco with the whip in one section reinforced that circus notion where Cuesta, as another character, was slashing an invisible character and, in doing so, resembled a lion tamer. Others thought a circus interpretation would be seen as too light, but switched the criticism to being that the wall was too big and made for too many changes in viewing. Still others thought the wall represented the hugeness of both the story and the impact on the people of the area – and therefore concluded it should stay as is. All this will give the creative staff something to think about.

Near the mid-point in Cuesta’s performance, Slowiak takes to a podium way off audience right. From there he gives a summary history of the devastation on the peoples of this area and in Africa, especially the Congo. He enumerates the millions who died or were exploited for sex or slavery. It was a grim reciting, but dramatically it’s meant to give significance to the single person we see mourning for his tribe. The problem was huge and destructive for its day.

Everyone in attendance was seemingly taken aback at what the search for natural rubber to make bicycle and automobile tires caused. As Slowiak noted after the performance, this story represents the period before British industry men took splices from Brazilian plants and sailed to Southeast Asia to establish rubber plantations that most people are familiar with. “The Devil’s Milk Trilogy” is largely an untold but important story.

Although everyone seemingly liked the interlude with Slowiak’s summary, some wished he were more visible, perhaps even on stage. Others thought having him at the podium with a spotlight on him was sufficient. Still others thought he could just be a voice, seemingly coming out of the nowhere but authoritative nevertheless. Again, production staff have much to consider.

I think everyone present at the rehearsal I attended would agree that once this section, “Death of a Man,” is presented with the completed trilogy, it will be vivid, gripping and provocative. New World Performance Laboratory plans to have feedback sections after each of the full performances to give audience members a chance to comment and to discover even more factual information that ties directly to Akron’s history.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·