Paley Center forum on data journalism explores expanding opportunities for storytelling

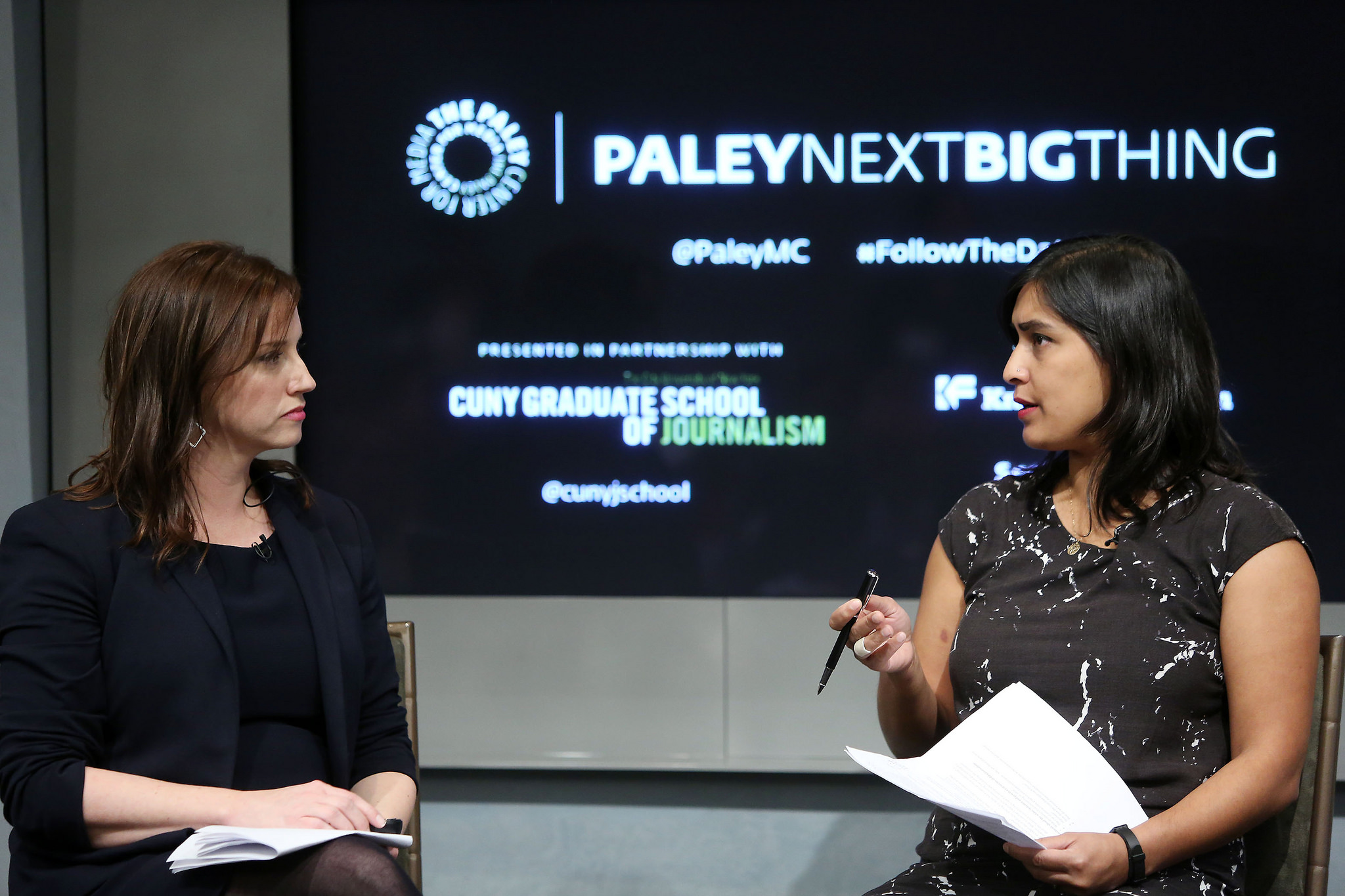

Above: Lee Glendinning, editor of the Guardian US, speaks with Shazna Nessa, Knight Foundation journalism program director. Photo by Paley Media Center on Flickr.

Even as news organizations fight to gain financial footing in an Internet age that has eroded advertising revenues, this era is birthing innovations in digital journalism that can enlarge storytelling and news audiences.

That was the broad message from journalists—and non-journalists who increasingly are helping to direct and shape newsroom staffs—during the latest installment of the “Next Big Thing” at the Paley Center for Media in New York, a forum supported by Knight Foundation.

“I regard the rise of data journalism and associated digital capabilities as the biggest reinvention of anything this side of the printing press … that has fundamentally changed journalism,” ProPublica Executive Chairman Paul Steiger said, at the start of the “2020 Vision of Data Journalism” panel he moderated.

The Internet, he added, has upended traditional journalism, especially its revenue models. “On the other hand, the opportunities it’s opening up are phenomenal, ” said Steiger, who also serves on Knight Foundation’s board of trustees.

Emily Bell, founding director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia Journalism School, speaking as part of a panel, with ProPublica Executive Chairman Paul Steiger at right.

Paley and the City University of New York (CUNY) Graduate School of Journalism, both Knight Foundation grantees, co-hosted the Wednesday morning forum. The event honored data journalism innovators: former software developer Meredith Broussard, a New York University Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute professor who researches the use of artificial intelligence in investigative reporting; former financial software developer Brian Chirls, chief executive officer of datavized, a consultancy on data visualization tools; and statistician Rachel Schutt, senior vice president for data science at News Corp., owners of The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones Newswire and the New York Post.

While strong reporting by journalists remains the backbone of the news business, non-journalists from technology, science and related backgrounds increasingly are essential to newsrooms staffs, Lee Glendinning, editor of the Guardian US, said during the morning conversation with Shazna Nessa, Knight’s director of journalism.

Those non-journalists have honed different skills, Glendinning added. But “as ever, they need to have ideas” that are strictly news-related.

At least for now, finding professionals whose main focus has been journalism but who also are equipped with the digital skills required for this moment has been difficult, agreed Glendinning and Nessa, formerly an Associated Press deputy managing editor whose initial career was in Internet technology and interactive design.

“It’s hard to find people with these skills sets,” Glendinning said. “We want folks with news judgment. We want folks who know data and spreadsheets. We want good writers … who can write good headlines and pitch [story] ideas.”

They are the kinds of professionals capable of producing, for example, “The Count: People killed by police in the US,” a Guardian US interactive database, partly built on information supplied by readers and others in the 50 states. It’s comprised of photographs, charts, maps, numbers and narrative; the status of investigations into those slayings, if investigations were ordered; which agencies conduct the investigations; and so on. (While the FBI announced this week that it will start tallying the police slayings, the U.S. government currently does not have those comprehensive figures.)

Glendinning said data show that such visuals and interactivity are often popular among readers. Those empirical insights sometimes may indicate that “a headline’s not working. ‘Wow, this is what [should be the next step],’” Glendinning said, adding a cautionary note. “It’s an informative tool but it doesn’t dictate” what stories get covered.

During the panel discussion moderated by ProPublica’s Steiger, physicist Haile Owusu, chief data scientist at Mashable, told the audience that Mashable hired him in part, to assess readers’ habits and how those habits might shape the kinds of stories its reporters pursue and by what means. “I came … with the intent to see how content diffused online,” Owusu said. “What we wanted to understand … post-publication [is] what happens … We built a tool that not only curates content but predicts the engagement that content will get.”

Those metrics may help “reduce labor for journalists,” he added. It might influence decisions over what’s worth investigating and what isn’t.

Deciding which topics, communities, people and other items should make the news has long been a hot topic among news consumers and journalists alike. Owusu ceded that fact, while talking to a cluster of audience members following that panel. He said weighing the newsworthiness of potential stories against the need to help newsrooms make a profit is, perhaps, trickier now than ever. He, too, is still looking for the right balance and right answers, he said.

Newsrooms hoping to sustain themselves are confronting the same type of questions, while also moving in step with changes of an increasingly digital work, suggested Columbia Journalism School’s Emily Bell, who also was on Steiger’s panel.

Columbia is seeing growing interest in its two-year journalism-computer science dual degree program, said Bell, a former editor-in-chief of the Guardian and director of Columbia’s Tow Center for Digital Journalism, which also receives Knight support. It projected that 15 students would enroll in the current academic year’s data journalism Master of Science program; it landed 30.

“We might continue to be great school for writers but, unless we put data with that, we will not be a very great school for very long.”

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·