‘Queen of Thursdays,’ documenting a Cuban ballerina’s rise and exile, to premiere at the Miami International Film Festival

Rosario Suárez in captured video images from Queen of Thursdays.

The images need no commentary. On stage, Rosario Suárez, the former prima ballerina of the Ballet Nacional de Cuba, can be simply breathtaking. She is an expressive performer with a dazzling technique. Her whole approach shows a refined blend of grace and power, elegance and a deep sensuality.

But in the life of an artist, talent, even great talent, dedication and discipline are no guarantees of success or a happy ending. Forces large and small—from historic political circumstances to simple human envy—can shape a career and be critical in reaching a truly transcendent status.

For years a star-in-the-making, rarely showcased in the weekend performances, Suárez became the headliner of the company’s Thursday programs. Thus, she became la reina de los jueves, the Queen of Thursdays. Her story has now made its way to film in a documentary that will premiere at the Miami International Film Festival, fittingly, on Thursday evening. “Queen of Thursdays” is also competing for the Knight Documentary Achievement Award, where audience members vote on their favorite to win a $10,000 prize funded by Knight Foundation.

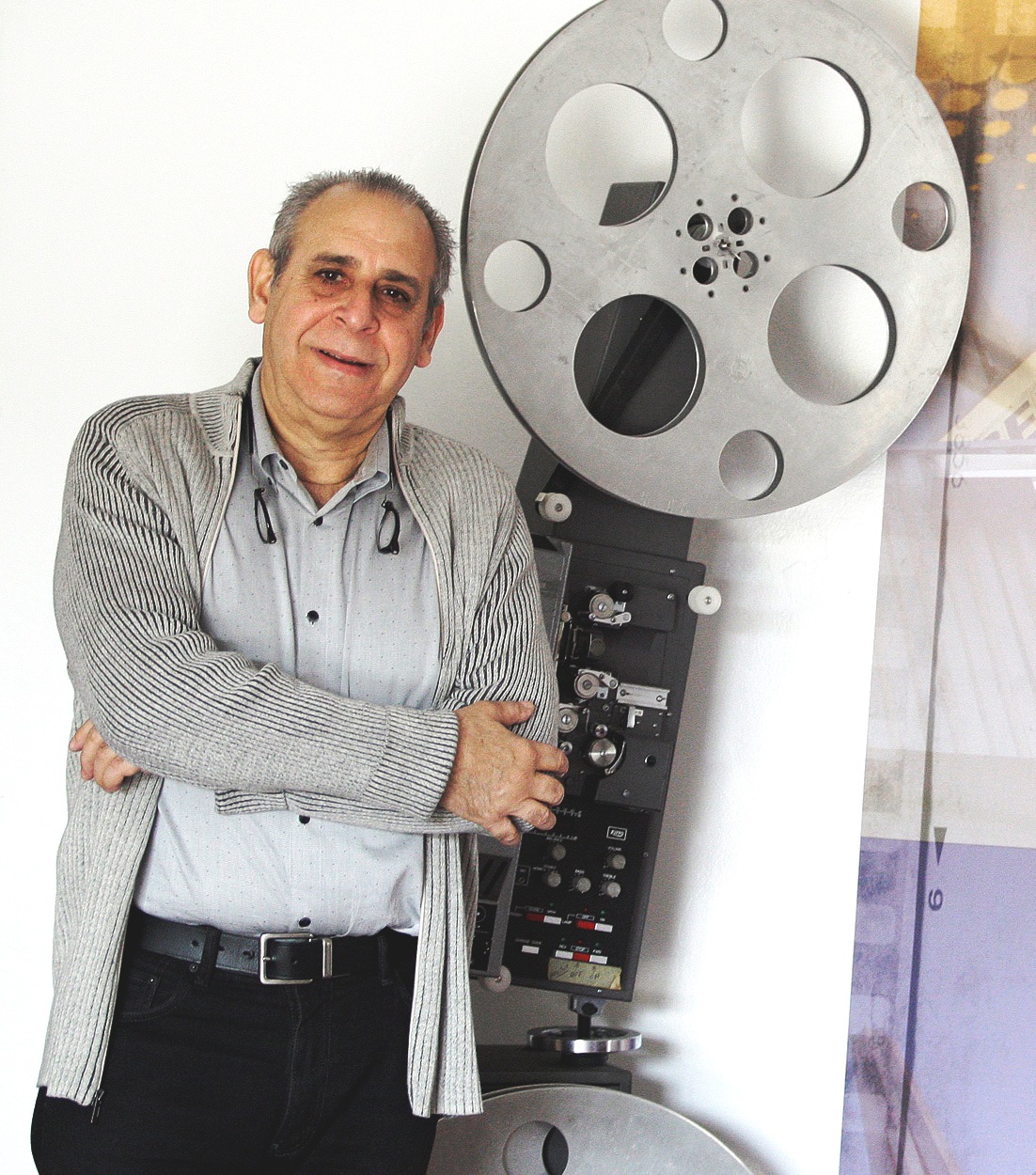

‘Queen of Thursdays’ director Orlando Rojas.

The film, directed by Orlando Rojas and co-written by Rojas and Dennis Scholl, a filmmaker and former vice president for the arts at Knight Foundation, follows Suárez from her beginnings in Havana, through her rise through the ranks, her battles to find her place in the dance world in her own country and, finally, to a life in exile.

Beloved by audiences and respected by critics, Suárez remained for years in the shadow of dancer and choreographer Alicia Alonso, the all-powerful founder, prima ballerina assoluta and director of the Ballet Nacional de Cuba. By the time she was finally elevated to prima ballerina, Suárez had reached an age where dancers are beginning to consider retirement. And when a family crisis convinces her to leave Cuba, she finds herself caught between worlds and unprepared for a dance business more appreciative of her talents for marketing and fundraising than her grand jetés or exquisite port de bras.

“It’s a movie about the challenge to be an artist, wherever you may be,” says Rojas, a much decorated, Miami-based Cuban scriptwriter and filmmaker who himself went into exile in 2003. “Being an artist is very difficult in Cuba—and it’s very difficult here. Being an artist is a condition that puts you always against the collective, which in Cuba, especially, is a very strong concept. That is very difficult. Then you add to it exile, politics, founder’s syndrome … and the odds are daunting.”

For Scholl, a seven-time Emmy winner, “Queen of Thursdays” underscores the fact that “no matter how artistically excellent you are, it’s hard to be an artist.”

“In my job I see many, many artists,” says Scholl, who is also a renowned collector of contemporary art. “And I feel such dismay when someone like Rosario does not get the rewards she deserves for her talent and hard work. She is a great artist at the pinnacle of her discipline—but her story also shows you that artistic excellence does not always equate with success.”

Featuring interviews of Suárez, 62,and extensive footage of her performances through the years, “Queen of Thursdays” documents her brilliance as a dancer as it offers a window into some of the obstacles that defined her career: a dance company suffering from a cult of personality, which mirrors the political structure afflicting Cuba; the conflict in having to defy Alonso, an artist she deeply admires, and her disillusionment with a revolution that formed her as dancer.

In fact, Suárez leaves the Ballet Nacional de Cuba to become one of the main figures of Ballet Teatro de La Habana. The new company is the first artistic group created outside the official institutions of the revolution. It’s a valiant effort, but it dissolves after two years and Suárez eventually rejoins the Ballet Nacional de Cuba. After a honeymoon period of sorts, and one too many challenges to Alonso’s rule, Suárez finds herself removed from the company’s schedule. With her options in Cuba dwindling and worried about her daughter’s future, she goes into exile. Now in Miami, where she still resides, Suárez faces new challenges, including her lack of a marketable name (having been in Alonso’s shadow) and the harsh realities of a dance world ruled by the laws of the marketplace.

“In Rosario’s case there is a deep honesty and sincerity in what she does and what she says. And in part because of it, she couldn’t ever promote herself as a dancer or as a person,” explains Rojas, who has known Suárez personally since 1967, when she was just a young dancer joining the ballet. “There’s a sense of honor in her that is very inspirational. Even in her struggles with Alicia, she can’t bring herself to speak ill of her. It’s the respect of a great artist for a great artist.”

And just as she can’t bring herself to publicly criticize Alonso, Suárez, part of the first generation of dancers formed in the Cuban school of ballet, clearly agonizes as she parts ways with the revolution. The pain and disenchantment is audible in her voice when she finally allows herself to ask out loud: “Why don’t I have the right to buy medicine for my daughter? What have we been talking about in [Cuba] all these years? None of us [artists] did what we did to have a house with a swimming pool.”

For Scholl, Suárez’s conflicts with Alonso and the Cuban Revolution, evoke a Shakespearean drama. “Why would someone with a limited amount of dancing time left stay in Cuba? Because she is a daughter of the revolution—and yet the revolution has failed her,” Scholl says. “The people who were supposed to be giving her the opportunities are keeping them for themselves.”

The film is bookended by two passages from Albert Camus’ “The Myth of Sisyphus.”

The opening quote sets the tone: “The gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. They had thought with some reason that there is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor.” The closing one might sum up the condition of an artist’s life: “The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

For Scholl, artists like Rosario Suárez are simply “doomed to push the rock up the mountain.”

“Anybody who dances as long as she has is not doing it because she thinks she’s going to get to the top of the mountain. [If you are a true artist], you make art because you must.”

With “Queen of Thursdays,” “I’d like people to come away remembering how hard it is to live a life as an artist,” he says. “You can almost never do it on your own terms; it takes unbelievable commitment and often compromise, and at the end, what you get from making art, is the joy of making art.”

Fernando González is a Miami-based arts and culture writer. He can be reached via email at [email protected].

Rosario Suárez is scheduled to appear at the world premiere of “Queen of Thursdays” at 7 p.m. Thursday, March 10, at the Miami International Film Festival. Visit 2016.miamifilmfestival.com for more details.

Rosario Suárez.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·