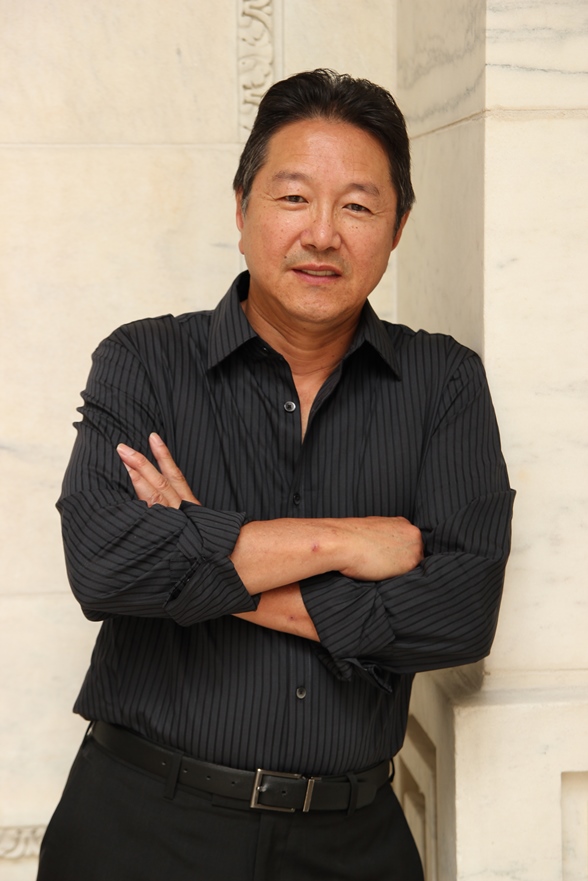

Rick Shiomi debuts his first new play since leaving Mu Performing Arts

Rick Shiomi’s latest work adapts Xinran Xue’s book about Chinese women’s experiences under the nation’s One-Child Policy into a moving, complex play.

“Message from an Unknown Chinese Mother” is playwright and director Rick Shiomi’s first new work since his departure from Mu Performing Arts (a Knight Arts grantee) last year. At Saturday’s stripped-down workshop performance of the play at Dreamland Arts, Shiomi described the work as “about halfway there;” he said he had some tweaking yet to do, some rewriting, but that he hoped to be ready to shop it around for a full stage production sometime next year.

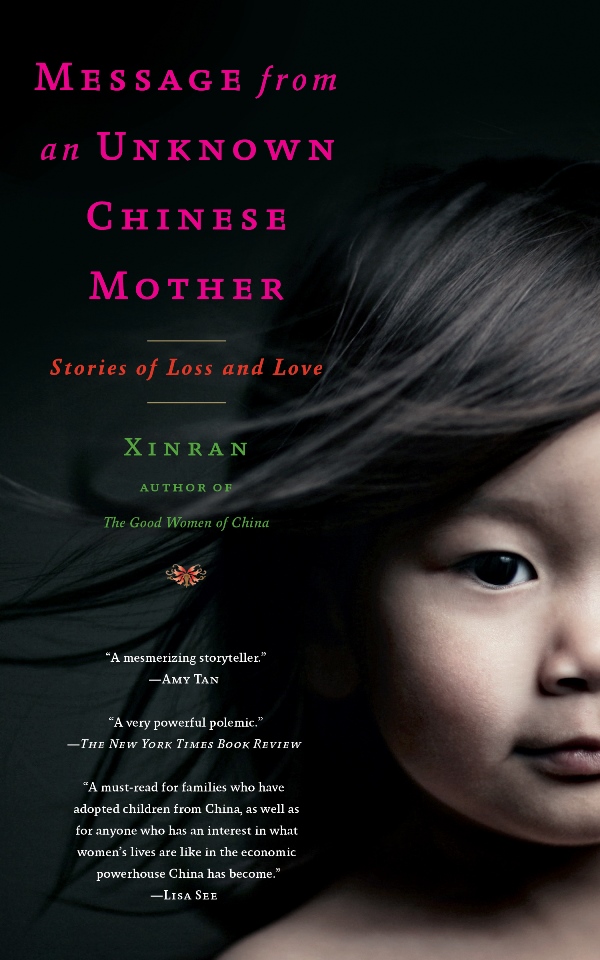

Shiomi’s play is based on a memoir by the same name written by expat Chinese journalist-turned-activist Xinran Xue. It’s a collection of first-person accounts of the lived consequences of China’s One-Child Policy with a sampling of the stories behind all the nameless girl babies abandoned (or worse) by their birth families from the 1980s on. Specifically, Xinran’s accounts are concerned with their mothers, women caught between the nation’s strict population-control policies and an equally rigid cultural tradition that regards daughters as burdensome, and which vests only sons with the requisite spiritual responsibilities and material property to carry on the family line.

In Shiomi’s adaptation of the book, we meet “waiters” – women who abandon their infants in a moment of grim desperation and then quickly change their minds, returning to find their babies long gone, moved and unaccounted for in China’s vast, often ad hoc “orphanage” system. We see the midwives hired to summarily dispatch unwanted baby girls at birth and the naïve, bereft young women whose families pay for their services. We meet the itinerant “extra-birth guerilla troops” – usually rural couples, well removed from the watchful eyes of party “cadres” in the urban centers – who bear and then abandon baby girl after baby girl, moving on after each failed attempt at a son, starting anew in the desperate hope that the next pregnancy might result in a boy child whose birth will offer sufficient fulfillment of filial responsibility (and attendant material security) to return to their kin back home.

Rick Shiomi. Photo: Lia Chang

Thankfully, Shiomi punctuates these intimate, terrible vignettes with dryly delivered contextual information – birth rate (and suicide) statistics, demographic and historical tidbits. The facts and figures propelling these linked narratives along are offered up by a dispassionate chorus, a rotation of unnamed players. It’s an efficient device by which to articulate something of the perceived necessity driving China’s draconian reproductive mandates; these sections also give a sense of the complicated historical sweep behind the awful particulars of each individual mother’s tale. The shift in tone and oddly upbeat delivery of these interstitial sections is admittedly jarring, but it’s a welcome, maybe necessary reprieve nonetheless.

Indeed, in a talk-back session after the show, a couple in the audience – adoptive parents to children from India – remarked on the bleakness of the stories in the play. They asked Shiomi why he couldn’t include more “glimmers of hope,” a note of optimism to offset to the weight of sadness. Why not follow the sad stories with, say, news of successful placements and thriving kids? Or, they offered, maybe he could say more about the growing opportunities for reconnection between international adoptees and their native countries and cultural traditions, if not their birth families.

Sarah Ochs, who played Xinran, offered a response that gets at the heart of what’s valuable about Shiomi’s efforts here, I think. She said she thought it was important to hold the line, to steer clear of tidy, more palatable versions of Chinese women’s experiences. Instead, she said, we have a responsibility to sit with their unmitigated, unsanitized personal accounts; we owe it to the mothers of these vast numbers of babies adopted overseas to open our ears to the heartbreak and impossibly difficult choices that cost them their children (and gave many among us our own).

A Korean-born adoptee herself, Ochs observed that we’re all already conversant with the perspectives of European and American adoptive parents – they’re privileged with most of the agency in these transactions, endowed with a ready visibility born of age and affluence that enables them to share their points of view on such adoptions widely. Likewise, she says, the Asian-American adoptee community is coming of age, and they’re beginning to publish books and articles as well, so their stories and struggles are also beginning to inform the larger conversations about international adoption. But, she said, we still don’t hear much that sheds light on the birth families’ experiences. The birth mothers, especially, have little or no voice – they’re often shamed and stigmatized at home, bereft and forgotten by the adoption narrative, but indelibly marked by their lost and relinquished children.

Xinran Xue was a reporter and broadcaster in China for many years. The stories here are gleaned from her years hosting a late-night radio program focused on women’s issues and stories.

Ochs said she’s proud of the play’s fidelity to the thorniness of Chinese women’s lived experiences. “It’s important to recognize that, as uncomfortable as it may be for us to hear, for these birth mothers there often aren’t ‘glimmers of hope’ – their lives are pretty hopeless.”

And it’s true: when you next see Shiomi’s new play, even with all the polish of full stage production, it won’t be merely entertainment. That’s not to say it’s at all dreary or difficult to sit through either. On the contrary, the writing’s quite smart and the dialogue often witty. These are uniformly compelling stories well told. This is serious business he’s after, but also deeply humane and engaging.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·