Should platforms be regulated? A new survey says yes.

In the two years since the 2016 election, the role major social media and technology companies like Facebook, Google and Twitter play in enabling (or corroding) an informed society has become an issue of increasing concern.

It is well known at this stage that these platforms are a key destination for news. They regularly make decisions about who gets to provide information and who gets to see it. But as misinformation infects newsfeeds, and information echo chambers become the norm, should there be rules that govern their role as news editors?

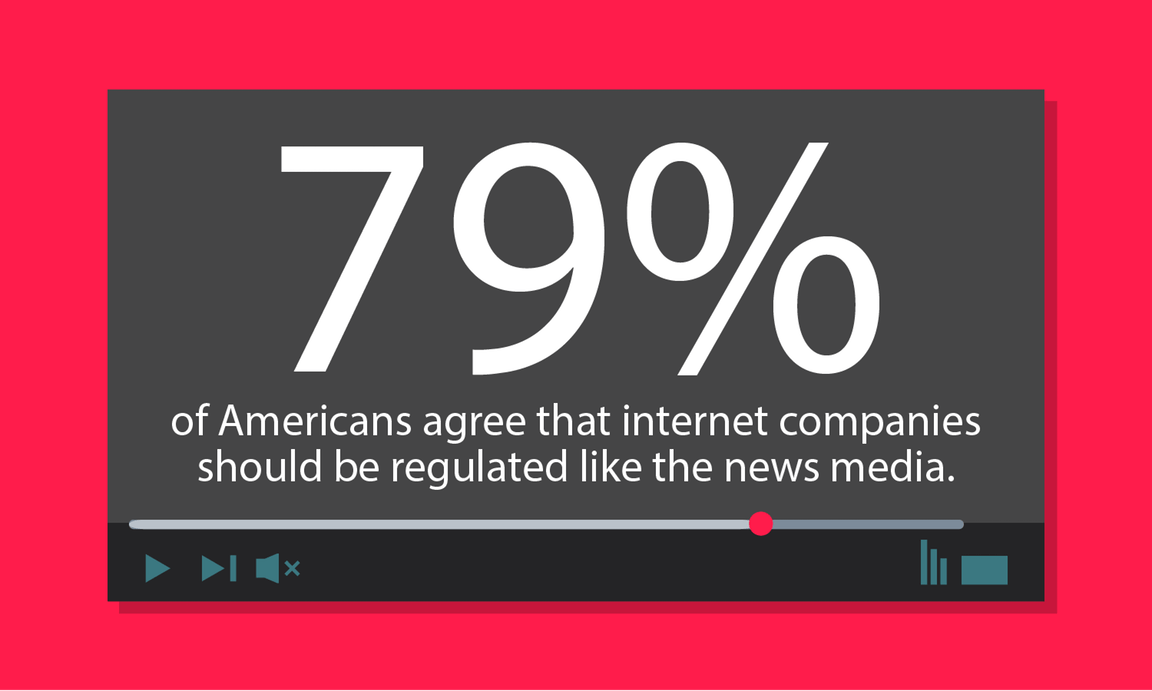

A new survey says yes — almost eight in 10 Americans agree that these companies should be subject to the same rules and regulations as newspapers and television networks that are responsible for the content they publish. The survey is part of a series of reports released by Knight Foundation and Gallup over the course of the year exploring American perceptions of trust, media and democracy.

Over 20 years ago, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 — in many ways the first law of internet — codified in law that those providing internet services are not publishers. They cannot be held responsible for content posted by third parties.

Many regard this as a vital legal principle responsible for much of the growth of the internet. After all, if Google in its garage days could be sued for linking to a popular website full of slander, or Facebook in its dorm days could be sued because someone posted indecent content, they may never have grown up to become the ubiquitous and essential services they are today.

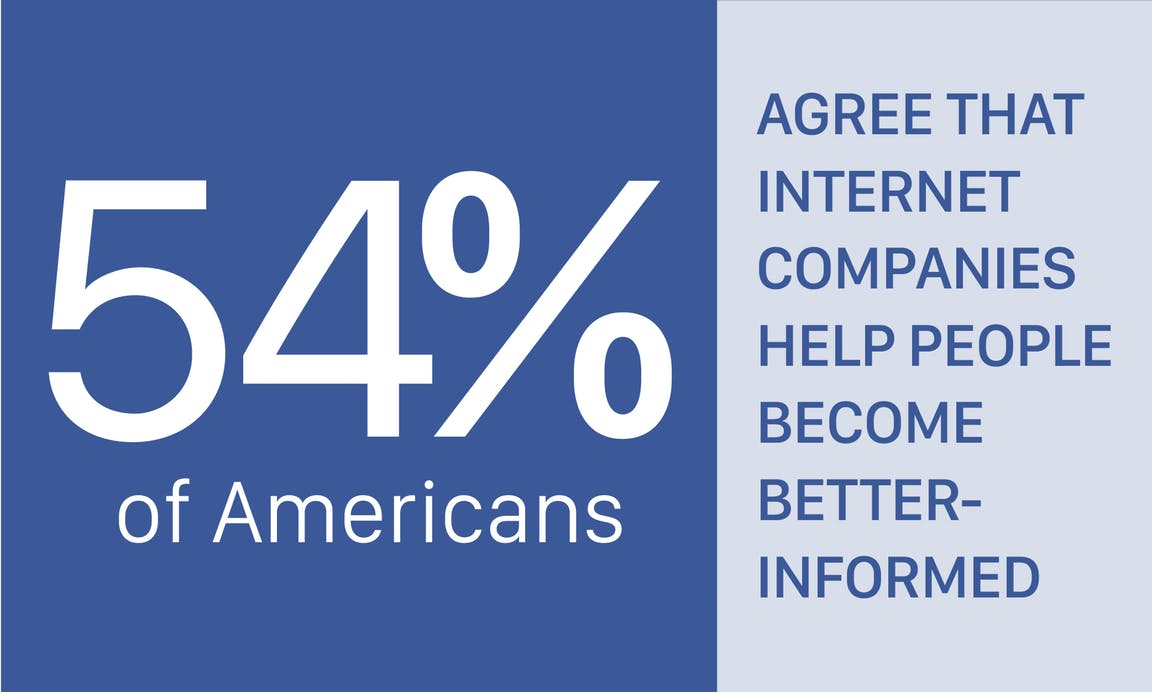

Yet the modern realities of these services and their reach has left society with some uncomfortable questions about their responsibilities. While the majority of U.S. adults (54 percent), especially those ages 18 to 34 (66 percent), believe that internet companies do help people stay better informed, Americans increasingly expect tech companies to take on new obligations as information distributors.

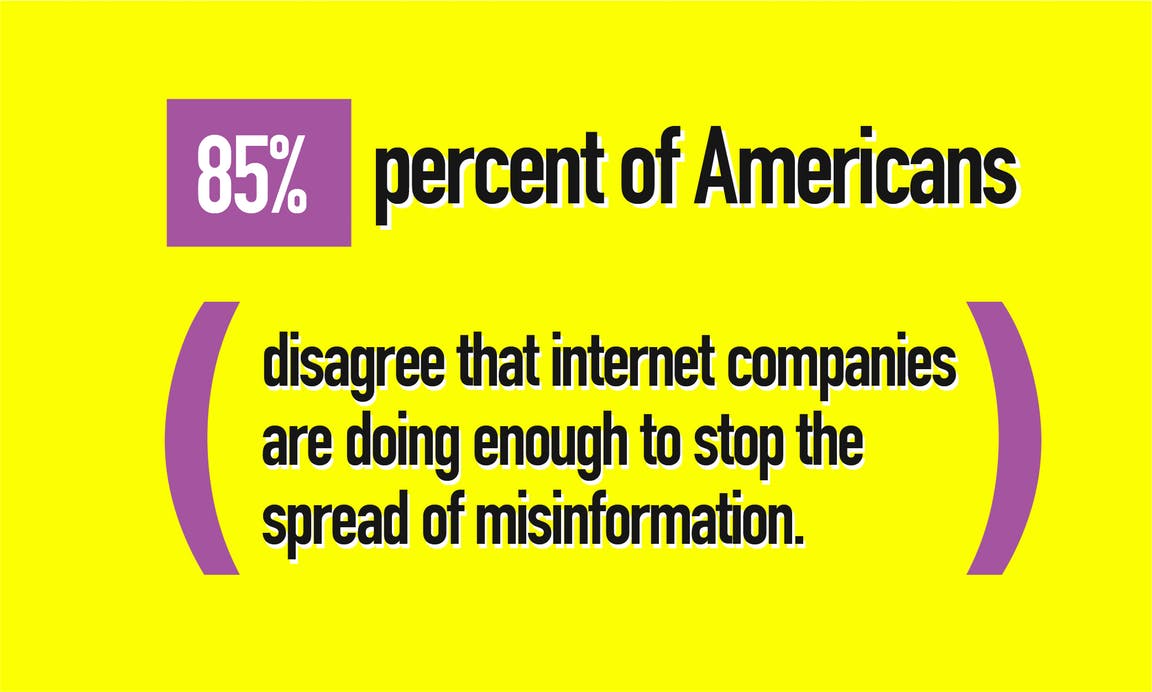

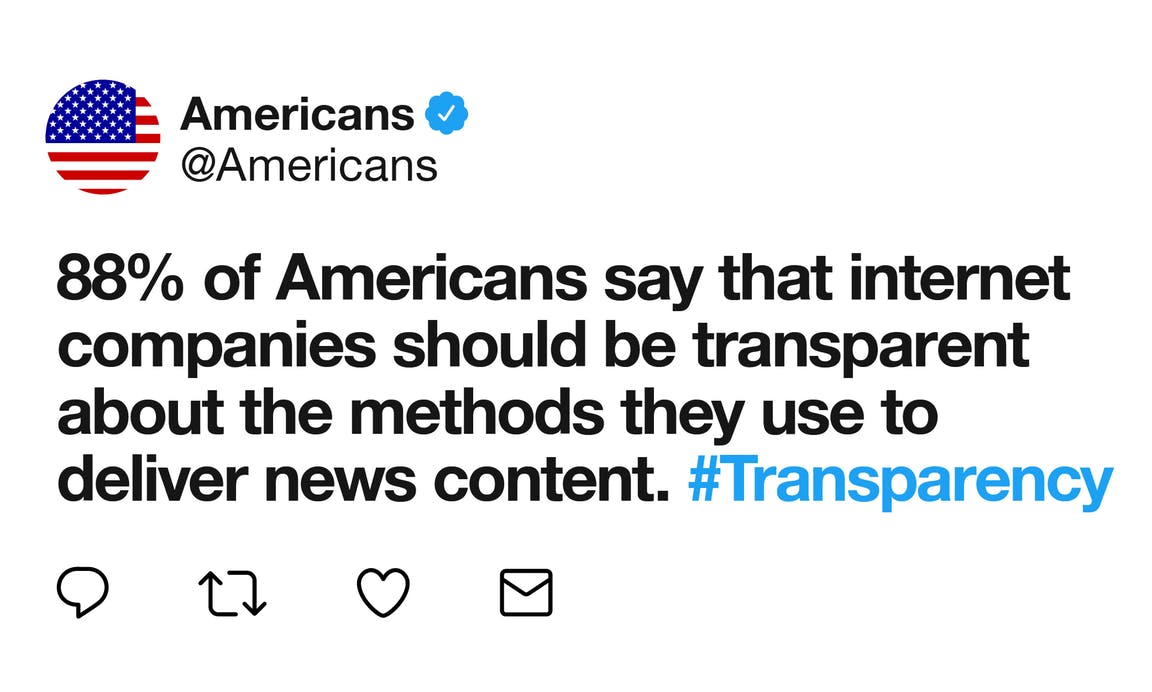

Our survey found that a large majority think tech companies should do more to stop the spread of misinformation and are uncomfortable with the level of personalization of these services when it comes to news. Most (88 percent) feel that internet companies should disclose the methods they use to deliver news content.

Three quarters (73 percent) say that all users should be shown the same topics as opposed to being shown topics based on their interest and activity. And eight in 10 say that, for a given topic, all users should be shown items from the same news organizations. Only 17 percent of respondents reported they would prefer these companies to show each user news from sources they seem to prefer based on their interests and activity.

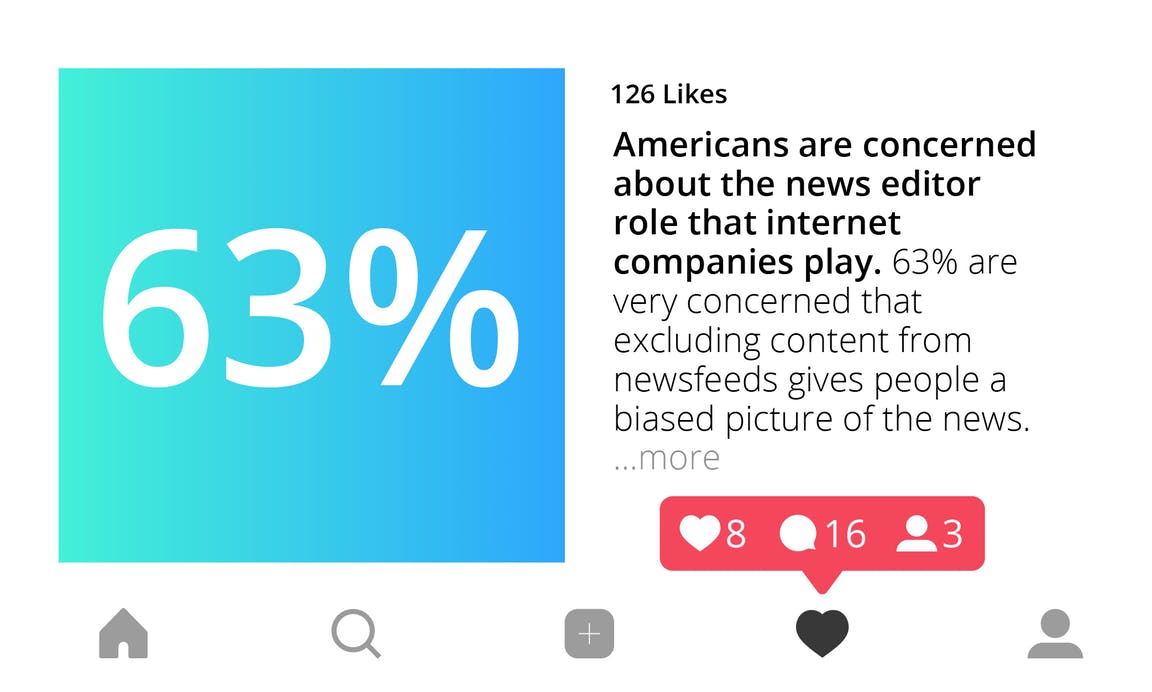

While misinformation was seen as a problem that companies should address — respondents were less sure about how to do this. A strong majority (80 percent) support the idea of major internet companies being responsible for excluding content that the companies suspect is misinformation. Yet Americans are also concerned that removing content would lead to biased pictures of the news. In addition, they worry that it would potentially increase the influence that companies have in reporting news related to their own preferred points of view and restrict the expression of certain perspectives.

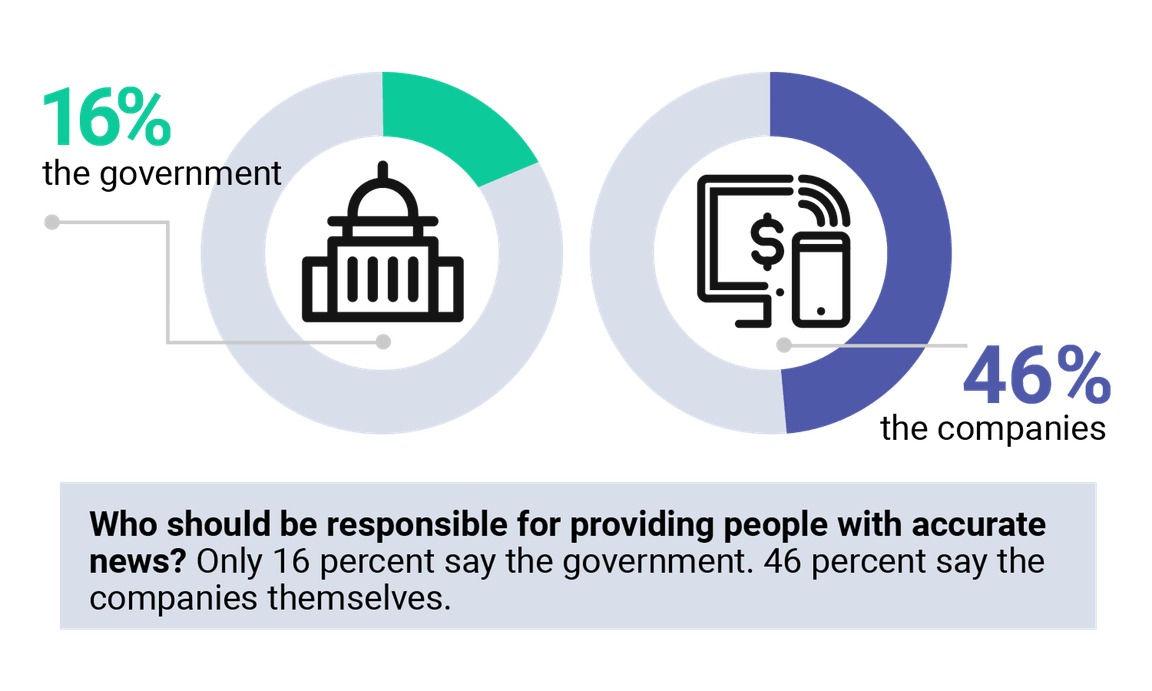

In addition, while Americans favor regulations on tech companies, they are not looking to the government to ensure that these companies provide their users with accurate and unbiased news. They see the responsibility as falling more on the companies themselves (46 percent) or their users (38 percent).

There are obvious tensions in public perceptions on these issues, and a seeming disconnect between expressed points of view and behavior. After all, people may decry personalization, but the value of these companies and their revenues would suggest that most users and consumers do, in fact, appreciate the level of personalization that the internet provides.

Or, perhaps, people want to eat their vegetables when it comes to staying informed, but acknowledge they’ll devour cookies if offered them instead.

What’s clear is that the public is struggling to reconcile their growing use of these services to stay informed with the effects of an information environment governed by a different set of rules, practices and norms than legacy media. And in that the broader public resembles lawmakers and leaders at these companies themselves.

These are hard questions for the future of our informed society. We hope this research enables a more informed discussion about how to answer them.

Sam Gill is VP/Communities and Impact at Knight Foundation. Follow him on Twitter @thesamgill.

-

Information and Society / Report

-

Information and Society / Report

-

Information and Society / Report

-

Information and Society / Report

-

Information and Society / Report

-

Information and Society / Report

-

Information and Society / Report

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·