Tech and the fine art of complicity

What are the opportunities for technology in the arts – and what threats does it pose? Knight Foundation, which recently launched an open call for ideas to use technology to connect people to the arts, asked leaders in the field to answer that question. Here, Jer Thorp, a data artist and innovator-in-residence at the Library of Congress, answers with his own, provocative inquiry.

As an artist who works with technology, my daily practice is punctuated with questions: Which natural language processing algorithm should I be using? How well will this cheap webcam function in low light? What exactly does that error message mean?

Lately, though, I’ve been spending a lot of time dwelling on one question in particular:

How am I complicit?

Specifically, how are the works that I’m creating, the methods that I’m using to create them, and the ways that I am presenting them to the world supporting the agendas of Silicon Valley and the adjacent power structures of government?

Tech-based artist Zach Lieberman said in 2011 that “artists are the R&D department of humanity.” This might be true, but it’s not necessarily a good thing. In a field that is eager to demonstrate technical innovation, artists are often the first to uncover methodologies and approaches that, while intriguing, are fundamentally problematic. I learned this first hand after I released Just Landed in 2009, a piece that analyzed tweets to extract patterns of travel. While my intentions were good, I later learned that several advertisers saw the piece as a kind of instructional video for how personal data could be scraped, unbeknownst to users, from a Twitter feed. At no point in the development of Just Landed did I stop to consider the implications of the code I was writing, and how it might go on to be used. Unbeknownst to me, I was complicit in the acceleration of dangerous “big data” practices.

Complicity can also come though the medium in which we present our work. In 2017, Jeff Koons partnered with Snapchat to produce an Augmented Reality art piece, which rendered Koons’ iconic structures in real-world locations, visibly only through a Snapchat Lens. Though Koons has never been afraid to embrace commercialism, this project forces the user to embrace it as well: to view the artwork, people need to purchase specific hardware, install Snapchat, and agree to a Terms of Service that has concerning implications on user privacy and creative ownership. It seems clear to me in my own practice that any artwork that requires a user to agree to commercial use of personal data is fundamentally dangerous.

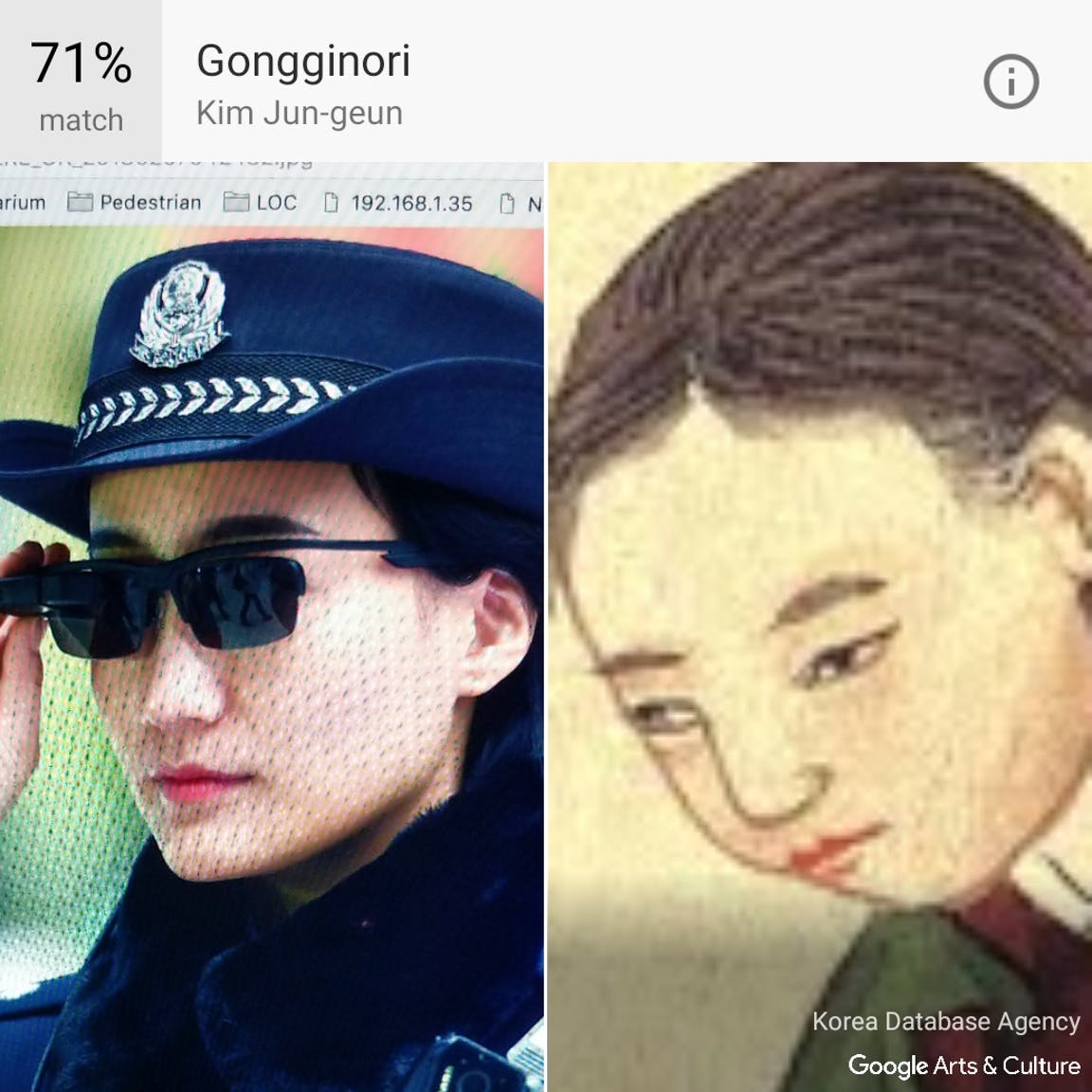

In January, Google added a feature to its heretofore unnoticed Arts and Culture app which allowed users to match their own selfies to artworks held by museums and galleries around the world. This project, though phenomenally popular, was rightly criticized for offering a depressingly thin experience for people of color, who are severely underrepresented in museum holdings. As well as being a prejudiced gatekeeper to the art experience, this tool seems to me to play another dangerous role: as a cheerleader for facial recognition. This playfully soft demonstration of face recognition is like using a taser to power a merry-go-round: it works, and it might be good PR, but it is certainly not matched to the real-world purpose of the technology.

Five years ago, artist Allison Burtch coined the term ‘cop art’ to describe tech-based works that abuse the same unbalanced power structures they are criticizing. Specifically, she pointed to artworks that surveil the viewer, and asked the question: How is the artist any different from the police?

As Facebook, Twitter and Google face a long-awaited moral reckoning, artists using technology must also be examining ourselves and our methods critically. How are we different from these corporations? How are we complicit?

For more about the open call for ideas on art and technology, visit prototypefund.org.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·