The painter as musician and the musician as painter

By Sebastian Spreng, Visual Artist and Classical Music Writer

Two recent DVDs show the relationship between opera and the visual arts from different angles: The Magic Flute, a painter’s vision of Mozart’s opera, and Wagner’s Tannhäuser, where the musician becomes a painter. They both constitute two controversial and absolutely fascinating variations on a similar theme.

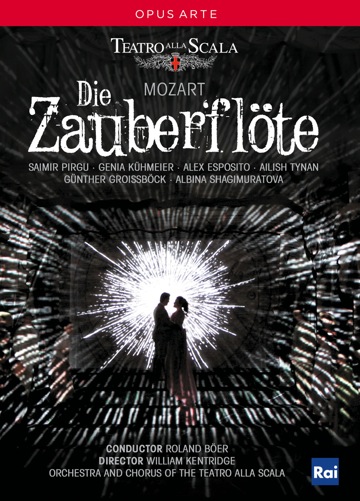

From David Hockney and Julie Taymor to the film versions by Ingmar Bergman and Kenneth Branagh, Die Zauberföte has been and will continue to be an endless source of inspiration for directors and set designers. The extent to which the visual aspect can outshine a musical performance has always been an obvious and heated subject of debate, but when masters of the visual arts are involved, that upstaging is foreseeable and, in many cases, inevitable. William Kentridge is no exception, and he is the main force in this Magic Flute, staged in Milan under the accomplished baton of Roland Böer.

The renowned South African artist, here also responsible as stage director, left his unmistakable stamp on a version that after its premiere at La Monnaie (2005) traveled to several opera houses before arriving at La Scala – where this DVD was recorded to earn unanimous praise from Milan’s difficult audiences. And there was good reason for that. Kentridge knows how to steer clear of artifice and hollow grandiosity to concentrate on the struggle between light and dark through an antique box camera that inverts negatives and ushers the audience into his vision of the opera. His brushstrokes, sketches, charcoals, chalks, blacks, whites, machines, allegories and animated games are marked by such rigor, such linear and monochromatic austerity, that they dazzle in their goldsmith-like simplicity. Though his powerful images inevitably prevail, his greatest virtue is his clear intent to seduce and captivate without attempting to overwhelm the musical aspect.

For Kentridge, Mozart’s opera symbolizes the power of music at the service of love. He sees the Pamina-Tamino relationship as Orpheus-Eurydice in reverse, with the powerful female character leading the prince. He sets the action in Africa during the late Victorian era suggesting the “light of reason” as a colonialist project of the Enlightenment. Greta Goiris’ beautiful costumes are conventional enough to make the point. Just as the boundaries of light and shadow blend, fade and disrupt each other, the characters’ ambiguities are played up, even the untouchable Sarastro’s.

Though Kentridge’s visual conceptualization and execution are more successful than his conventional stage directions, in the musical department the cast does nothing but shine, thanks to Saimir Pirgu’s Tamino, Genia Kühmeier’s Pamina, Albina Shagimuratova’s Queen of the Night, Günther Groissböck’s Sarastro and Alex Espósito’s Papageno.

Wrapped in Kentridge’s artistry, this Magic Flute poses more of an intellectual challenge than usual. It offers a different experience, an opportunity to explore the hidden meanings behind this artist’s charcoals and, ultimately, Mozart’s genius and the countless interpretations his glorious work allows it.

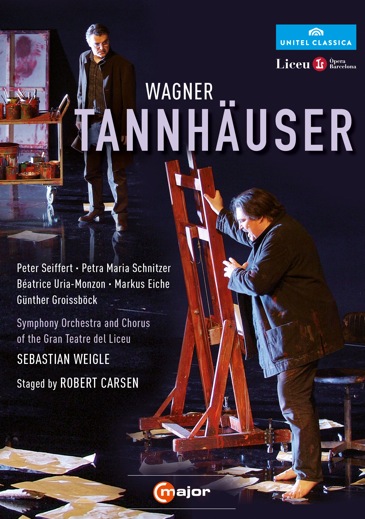

Also love’s light and darkness, here as sin and redemption, are the main ingredients of Wagner’s Tannhäuser, a challenging opera to produce from every angle. This revisionist version by Robert Carsen – always stamping superlative aesthetics on his daring productions – confronts, provokes and fascinates. The Canadian director portrays the medieval troubadour as a tormented modern visual artist, torn between his professional and personal lives. The result displays an original “turn of the screw.”

Controversial since its premieres (the first version opened in Dresden in 1845 and the revised in Paris in 1861), the opera unfolds within the triangle formed by Tannhäuser, Elisabeth (the virginal and sacred) and the goddess Venus (the carnal and profane). In Carsen’s vision, the Venusberg (the “Mount of Venus”) is the artist’s study and Venus is his model. Possessed by delirious inspiration in the midst of a creative and orchestral bacchanal, he paints a canvas the audience never sees, only the back of the stretcher. From there, the celebrated theme of “the artist and the model” assumes different shapes and meanings all the way to the unexpected grand finale of this powerful allegory of the artist’s role in Western society.

Carsen eliminates all religious references. The Minnesingers are Tannhäuser’s fellow artists, and the tournament in the second act is the opening of a competition exhibit – where the chorus are patrons entering through the center aisle – at the museum (Wartburg) of young Elisabeth’s father (the landgrave). Up to this point, the results are brilliant. It’s only in the third act that Carsen’s vision loses force when Elisabeth takes the model’s place, to be later complemented by Venus, now as two aspects of the same woman. At the end, a spectacular coup de théâtre erases all inconsistency: the artist prevails and triumphs, those who rejected him now are at his feet, and his work finally deserves a place in the museum along with other famous nudes, such as those of Rousseau, Courbet, Manet, Klimt, Picasso, Monet and others. Once again is the turn for “the artist and the model”. It’s an unpredicted and stunning conclusion in which Paul Steinberg’s austere set design, supported by Peter van Praet’s and Carsen’s superb lighting, achieves felicitous culmination and absolute logic.

Musically, the mainstay of the production is Peter Seiffert’s Tannhäuser. Apart from an occasional wide vibrato, for which he compensates with a powerful and polished timbre, his confidence and musicality are a pleasure to behold in an exhausting role that has defeated most Heldentenoren. With similar pros and cons, Petra Maria Schnitzer (Seiffert’s wife in real life) makes this Elisabeth one of her best roles, while French-Basque mezzo-soprano Beatriz Uria Monzón makes a beautiful Venus, although at instances the high tessitura can pose problems for her.

Markus Eiche, an elegant Wolfram, and Günther Groissböck, as the Landgrave, are both excellent, and well supported by a solid cast and the outstanding chorus of Barcelona’s Liceu, a theater that boasts an illustrious Wagnerian tradition. At the podium, Sebastian Weigle conducted a successful performance, despite a curious lack of synchronization with the chorus in the final section. Curious fans won’t want to miss Kasper Holten’s Copenhagen production, which, adopting a similar approach, treats the hero as a writer. (DECCA 0743390)

In sum, two daring takes on two opera classics waiting for a view and a well deserved later debate.

* DIE ZAUBERFLÖTE, DVD OPUS ARTE OA 1066 D

* TANNHÄUSER – UNITEL CLASSICA C MAJOR 7093080

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·