Universities must condemn hate speech without censorship

On May 5, 2020, Gallup and Knight Foundation released a new report on college students and their attitudes about Free Speech. Suzanne Nossel shares insights below. View the full report and additional insights here.

No one likes to admit to being against free speech. Whether on the playground or in the elementary school classroom, the virtues of free speech as a quintessential American value are drummed into children from a young age. But beneath the surface of Americans’ professed fealty to the First Amendment and the ideals of free speech lurks a shaky understanding of what these freedoms entail, why they matter and what it means to actually defend them.

The Gallup-Knight 2020 survey on the attitudes of U.S. undergraduates reveals both a surface-level commitment to the idea of free speech, and underlying reservations about what the precept dictates in practice. Knight and Gallup undertook the survey to measure to what degree a rising generation understands its constitutional rights, and stands ready to defend them. The results reveal that students’ appreciation of the First Amendment is wide but shallow, with a series of questions and doubts lingering just beneath the surface.

These doubts reveal misgivings about whether robust defense of free speech can be reconciled with social justice values including equality, inclusion and protection for the vulnerable. To raise a new generation that appreciates and embraces First Amendment freedoms, it will be essential to bridge gaps of knowledge and explain how free speech principles can accommodate, and even reinforce, other progressive values.

First, the good news for free speech. Fully 68% of students surveyed described citizen’s free speech rights as “extremely important” to democracy. Eighty-one percent of students support a campus setting that involves exposure to all kinds of speech, including that which may be offensive. Nearly three-fourths of those surveyed believe colleges should not be empowered to restrict speech on the basis that it may be offensive or upsetting to particular groups. But other questions reveal students hedging about unfettered expression.

The survey found that growing majorities of college students think their universities should be able to restrict the use of racial slurs (78%, up from 69% in 2016 from the same survey) and prohibit costumes that stereotype certain racial or ethnic groups (71%, up from 63% in 2016). Seventy-six percent of respondents reported that efforts to foster diversity and inclusion come into conflict with free speech rights either frequently (27%) or occasionally (49%), with black students far more likely than whites to encounter such conflicts often.

The survey revealed that women were twice as likely as men (23% to 11%), and black students nearly twice as likely as white students (28% to 15%), to prefer that colleges protect students by barring certain types of speech rather than permitting all types of speech. A fast rising proportion of students — 38%, up from 25% in 2017 — reported having been personally uncomfortable because of something someone said on campus, most often a comment concerning race or gender.

Not surprisingly, the tensions between diversity, inclusion and open expression, likely alongside other factors, are leading students to conclude that their free speech rights are less than fully secure. Whereas, in 2016, 73% of students surveyed said they believe free speech rights are secure, that percentage had dropped to 59% by 2020. The proportion of students reporting that the climate on their campus deters students from speaking openly rose from 54% in 2016 to 63% this year. Students believe that those with conservative views are less able than others to express themselves openly on campus. Students also report encroachments on expressive rights online, both in the form of people blocking views with which they disagree and because people are afraid of being attacked or shamed by antagonists.

The juxtaposition revealed in the survey results between students who believe in the First Amendment, but also harbor serious concerns about the damaging impact of speech, reflects a larger tension manifest in society. As the United States comes to grips with the pernicious and entrenched legacies of racial and gender inequality, citizens have become more acutely aware of the potential for certain types of speech, including slurs, to inflict lasting harm both on targeted individuals and on the larger climate for inclusion and equality. For many, recognizing those harms leads to a question about whether it would not make sense to curtail speech rights – for example through a campus ban on racist speech or stereotyped costumes – in the name of protecting the vulnerable from hurt and discomfort.

In order to build on the survey’s positive findings with respect to overall belief in free speech, it is vital to confront students’ reservations about the harmful impact of speech and to explain how free speech and values of diversity, equity and inclusion can be reconciled. PEN America has devoted a series of reports and a Guide to Campus Free Speech to spelling out how these vitally important sets of principles can be brought into alignment. We advocate steps that include a robust approach to deterring and addressing hate speech, but through measures that do not involve censorship or retaliation.

We urge universities to embrace a dual role as forums charged with making space for the expression of the widest possible range of ideas, and as speakers in their own right that can defend institutional values, support targeted students and even decry and condemn offensive speech, as long as it is not forbidden or punished. We encourage efforts to foster awareness of the differential impact of particular types of speech on vulnerable groups and to instill conscientiousness in the use of language, so that voluntary restraint and taboos obviate the need for more coercive measures to foster a campus environment that is hospitable to all.

The Gallup-Knight survey reveals both the potential that exists, and the work that needs to be done, in order to foster a campus environment that is truly open to all people and all ideas.

Suzanne Nossel is CEO of PEN America, a human rights and free expression organization.

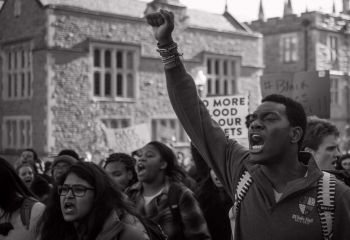

Photo (top) by Jason Leung on Unsplash

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·