Visitor from Vilnius

By Rachel Pastan, ICA

Curators spend a lot of time traveling to where the art is. ICA’s curators make studio visits and go to galleries all over Philadelphia and in New York. This summer one went to San Francisco and Tel Aviv, another got a travel grant for Paris, and a third flew to Munich and Rome. This is lovely, of course, and useful—indispensable, in fact—but it still leaves a lot of cities unvisited and a lot of art unseen, especially given the global explosion of the art world over the last decade. Time is short, and money is always tight, so last fall—at the invitation of the Knight Foundation—Curator Jenelle Porter came up with an idea: write a grant to bring curators from all over the world here to Philadelphia to fill us in on the art scene where they’re from. Travelogue, the resulting series of programs, runs all this year at ICA and offers a taste of Singapore, Paris, Beirut, Santiago, and—first up—Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania.

I was personally interested in seeing the curator from Vilnius because my family is rumored to be descended from a famous 18th-century sage and Talmudist, the Vilna Gaon (“Vilna” being the city’s old name). Probably it’s only a tale, but I thought I’d go and hear what Virginija Januskeviciute of the Contemporary Art Centre (CAC) had to say about her country and its art.

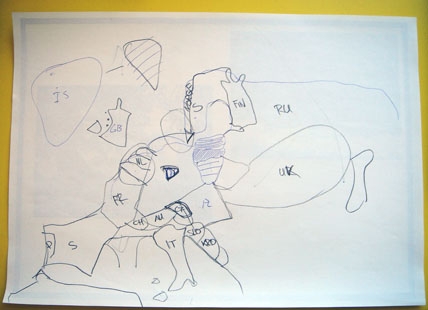

Lithuania, one of the three Baltic republics, is a tiny country with a population of less than three million squashed between big eastern European states (Poland, Ukraine) on the west and Russia on the east. To orient the audience, Virginija showed us hand-drawn maps her friends had made showing how Lithuania is situated in Europe—differently in the mind’s eye of different mappers. On one map, the Baltic states looked like a double-dip ice cream, with Lithuania the cone. She also showed photos of the drive from the airport to the center of the city: lots of trees and fields and Soviet-era apartment blocks. In addition to their museums, Vilnians (Vilniysts? Vilnyiks?) like to show visitors the landscape too. There are apparently lots of artists there, a legacy of the Soviet system under which an artist was a prestigious thing to be. That’s a nice thing to imagine: boys and girls saying to their parents, “Well, I thought about medical school, but I’ve decided to be a painter instead,” and the parents being overjoyed!

One piece Virginija showed was an image of a sentence inscribed on the CAC facade by the French artist and screenwriter Pierre Bismuth. It read (in Lithuanian), “Everybody is an artist, but only artists know it,” a reworking of Joseph Beuys’s maxim, “Everybody is an artist.” Googling around, I also found a gloomier version, by Lithuanian artist Juozas Laivys, which reads, “Art has ended, but only artists don’t know it.”

Like ICA, Virginija’s institution is non-collecting. Apparently, though, things have collected there anyway—sort of like in a lost and found. One of the recent exhibitions Virginija described was made up of art works that have washed up in the CAC over the last couple of decades. While she showed several images of pieces in this exhibition–by Bismuth, Blaziejus Krivickas, and Ulrich Ruckriem, for example–overall in the talk she didn’t show many particular artworks, saying at one point that she didn’t want to put the emphasis on specific works or specific artists. I wondered if this was a legacy of the Soviet system too.

She did show pictures of “black widows”—people made anonymous by black burkas walking all over the city to raise a debate about the use of public space. Apparently these apparitions caused panic in Vilnius, and participants were interrogated by the police. In a different approach to addressing politics in art, she described a recent project to reintroduce the bagel to a country whose once enormous Jewish population was virtually wiped out during World War Two. “A rare light-hearted Jewish event in Lithuania,” Virginija called it. I think the Vilna Gaon would have been pleased.

What can you learn about a place through its art? The impression I took away from this travelogue was that Lithuania is a country very much in search of itself, a country asking itself a lot of questions. How much of it is its history, and how much is it newly born? Should it exhibit the artifacts that have collected on its soil, or shut them away? Should it spend money to restore decaying Soviet statues or let them crumble? Should it serve bagels? Should it support artists?

It’s as though Lithuania itself is a shifting map that its citizens, artist and non-artist alike, are drawing freehand everyday. And the Lithuanian curators are doing what they can to present those maps—some of which are also works of art—to the world.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·