Wanted: More pro bono lawyers for journalists

The local news crisis matters for the simple reason that news provides the facts people need to govern themselves. If we lose local news, everything that follows is bad: less community debate, fewer candidates and voters, more expensive government and more corruption.

When local journalism works best, it helps people understand each other and solve common problems. But the more impactful stories require special effort. Enter the lawyers. Someone must sue to liberate public information. Someone must review stories before publication to protect journalists from frivolous lawsuits.

Knight Foundation and a relatively small group of other funders have over decades helped nonprofits create a legal safety net for journalists and news outlets.

But much of it still lives on year-to-year funding. And it’s still too small.

Rebuilding local news won’t go far without pro bono lawyers.

Together, journalists and lawyers can produce lasting results – not just for journalists, but for all Americans. Here’s a snapshot of documents obtained and stories reviewed, drawn from the 2023 annual reports of Knight grantees.

Reforming a city’s deadly police department

Vallejo, a mid-sized city in the San Francisco Bay Area, had one of the worst records of fatal shootings by police in the country: 17 deaths in nine years. But since Open Vallejo reported that officers were marking their badges after each fatal shooting, there has not been a single killing, roughly half the force left, two police chiefs have come and gone. The city settled a lawsuit, brought by the state attorney general, by agreeing to more than 100 reforms and an independent evaluator. ProJourn, which matches journalists with pro bono lawyers, helped make this possible by prying the public records from the city, including recent revelations about a death the city had covered up for a decade.

Fighting Massive Wage Theft in New York

More than 127,000 New Yorkers have been victims of wage theft in recent years; the state had failed to recover $79 million in back wages. When the New York Department of Labor would not release this public information, the Local Journalism Project at Cornell Law School’s First Amendment Clinic sued on behalf of the investigative outlet Documented. In August 2023, after a series by Documented and ProPublica, three state legislative bills were introduced to punish companies that wrongfully withhold wages.

All cold cases can’t be kept secret

A student from the Local Journalism Initiative of the Yale Law School’s Media Freedom and Information Access Clinic successfully argued before the state Supreme Court for a new standard for releasing cold case files. Police can’t just speculate that a case might be solved; they would need to show there is “at least a reasonable possibility.” The lawsuit came out of the making of the HBO documentary Murder on Middle Beach, about the brutal, unsolved 2010 murder of a Hartford woman in her front yard.

Guns in schools, autopsies, murder and Google’s water use

The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, under its Local Legal Initiative, works directly in selected states. Examples: * In Denver, news organizations won the release of records of a closed-door school board meeting that put armed police at schools — board incumbents were defeated at the polls. * In Pennsylvania, the Commonwealth Court ordered autopsy records must be released when inmates die in custody.* In Oklahoma, state and federal investigations were ordered after body-worn camera footage showed police repeatedly tasing a Choctaw Nation citizen who begged in vain for his life to be spared. * The Oregonian won records of Google’s massive use of water to cool its data centers. As part of a settlement, the company announced it would no longer treat water use as a trade secret.

Exposing secrets and more, at all levels

On the national level, the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University won access to opinions of the U.S. Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel showing the growth of executive branch power. Other documents include spyware reports from the CIA; revelations on employees at the Centers for Disease Control being barred from speaking to the public; details on efforts to declassify a U.S. intelligence report on the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, and how the State Department continues to use social media identifiers to vet visas.

Internationally, Knight supports the Committee to Protect Journalists, which in 2023 helped nearly 600 journalists in unsafe situations worldwide, particularly Palestinian journalists, and worked toward the release of 200 jailed journalists.

Knight legal service grantees do more than support newsgathering. The Knight Institute’s research in 2023, on topics such as “Algorithmic Amplification and Society,” was viewed 350,000 times and downloaded almost 10,000 times, and there were some 850 different news stories on the institute’s activities. As legacy media once did, Knight grantees look out for everyone’s free expression rights.

Today in this overheated nation, basic rights are melting away like polar ice caps, “slowly and suddenly,” says Bobby Block of the Florida First Amendment Foundation Unprecedented bans on books and on teachers discussing gender led the global Human Rights Watch to issue its most recent report not on Uganda or Pakistan but on the state of Florida.

Toward a stronger the safety net

Focusing on local news has shown us there simply aren’t enough pro bono attorneys helping reporters. All the Knight-funded programs, and most of the other members of the legal safety net – press associations, access nonprofits, legal clinics, newer Knight grantees such as Lawyers for Reporters (which specializes in business and employment law) – have more work than they can handle.

How can the number of local journalists fall but legal needs increase? Many traditional outlets have slashed legal budgets. Newer outlets don’t yet have legal budgets. There are more freelancers. To their credit, the remaining local journalists still care about the stories that matter most. Top training interests among journalists today include data, documents and media law.

Meanwhile, government secrets keep growing. The ugly truth is that most journalists who request public records don’t get them. The nonprofit MuckRock says journalists make up just a third of its users, but file half the requests. In the past year, they filed some 7,100 requests; 3,100 were fulfilled and 4,000 were not. Of those, 2,500 beg to be appealed, and, if warranted, end up in court.

Said MuckRock’s Michael Morisy: “In those thousands of cases … even a small amount of time from a pro bono lawyer can have an outsized impact.”

To continue to grow this network of pro bono lawyers, we need to better define it and measure its growth and impact. The report Standing Up For Journalism says “there is no systemic way of tracking or growing that help.” Other areas of pro bono law – immigration, voting rights, homelessness – are better known and better promoted. The report estimates that fewer than 1% of the nation’s 1.33 million attorneys have enough experience in newsgathering law to help journalists.

The report found 9 in 10 journalists want more pro bono legal help .

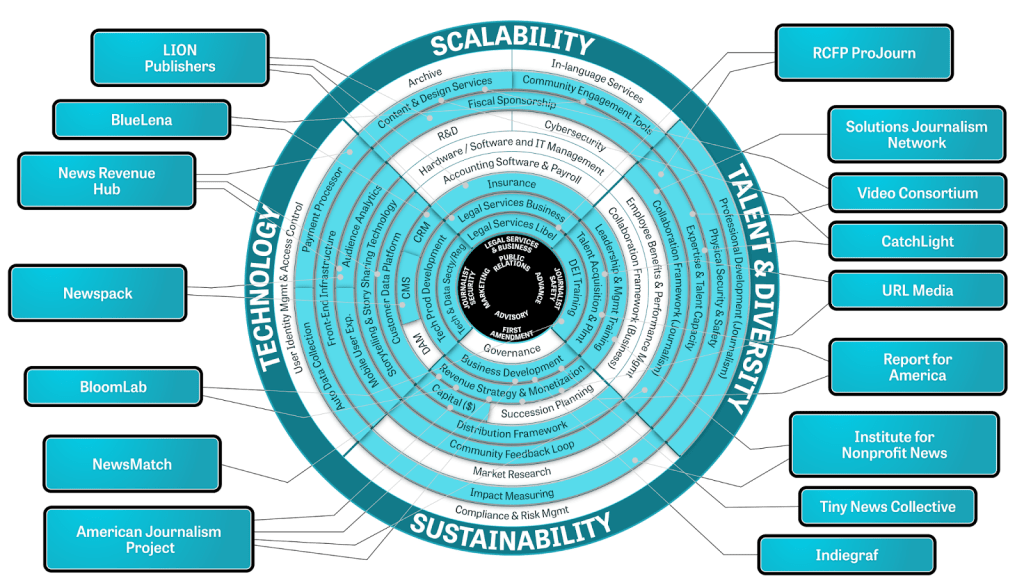

With news philanthropy increasing, it falls to the network and its funders to explain why legal aid grants are essential to the enabling environment – the infrastructure, if you will — that helps makes American journalism essential to the communities it serves.

Eric Newton is a consultant to Knight Foundation. A former staffer, he has helped develop First Amendment and journalism grants since 2001.

Recent Content

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·

-

Journalismarticle ·