Zeitgeist celebrates the pioneers of electronic music

This weekend, for the third annual Early Music Festival, Zeitgeist (a Knight Arts grantee) will celebrate the pioneers of electronic music: Karlheinz Stockhausen, Steve Reich, John Cage, Alvin Lucier, Michael Oldfield, Charles Dodge. I spoke with percussionist Heather Barringer by phone yesterday and asked her about the idea behind the ensemble’s mini-festival.

“From pop to more esoteric and experimental music, the electronic signal has had an incredible impact on furthering and magnifying the ability of music itself,” she says. “On the most basic level this technology has enabled people to hear sounds they’d never been able to hear before.” The use of electronic equipment meant that hearing sound was no longer an ephemeral experience. And electronic amplification allows sounds to reach across vast distances, too. “Think of the arena rock show – you can’t have that without amplification,” Barringer says. “And once you can record sound, you can bring it with you anywhere, replay it and listen again and again. And you can manipulate sounds electronically to create new aural experiences, sounds not just impossible but inconceivable before this technology existed.”

Barringer explains that, by using electronic technologies developed at the turn of the 20th century, all of a sudden, we were able hear and preserve music of all kinds, from all over the world – affording unprecedented access to various folk tunes and far-flung musical forms, as well as cross-pollinations among composers and performers simply unimaginable before the advent of this technology. “We could manipulate sounds and create effects never before heard; you could hear music from anywhere in the world. And all those sounds could be taken up and used by other composers for their own music creations,” she says.

“In this day and age, a competent 12-year-old can do all these things on a personal computer. The ideas behind the early days of electronic music – and the democratization of making music that followed in its wake – is still evident everywhere,” she says, from video games like “Guitar Hero” or karaoke to the amps and synthesizers used by high school garage bands. She says the cultural impact of this technology is hard to exaggerate: “The invention of electronic music marks a moment in music history where everything changes. Our relation to sound would never be the same.”

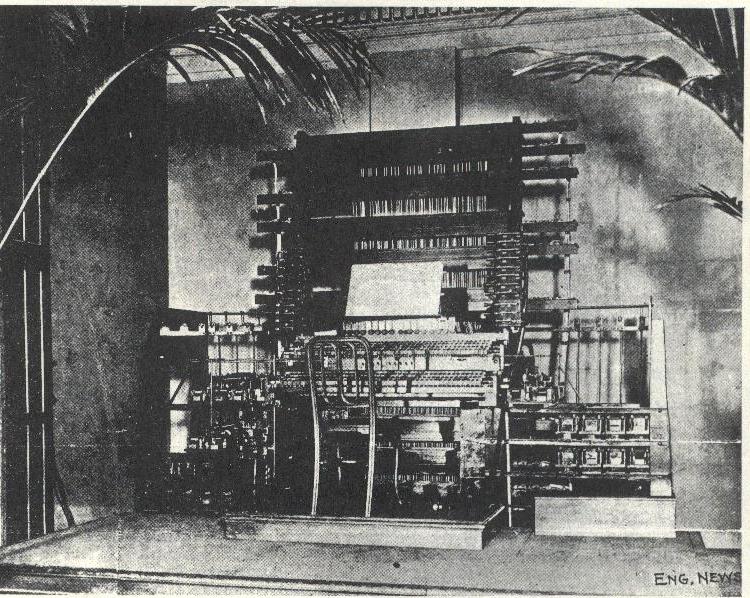

Barringer tells the story of one of the first electronic musical instruments: the telharmonium, patented in 1897 by Thaddeus Cahill. Intended as a modern improvement on the pipe organ, the first telharmonium was a massive, seven-ton instrument. The invention’s second, even grander incarnation – Cahill’s so-called “Dynamophone,” which debuted in 1906 – was even larger: more than 60 feet long, the whole shooting match clocked in at 200-some tons and was equipped with more than 2000 electrical switches and 145 gear-driven alternators (“dynamos”). A person playing this second-generation telharmonium could produce 36 notes per octave – making manifest nuances and gradations of sound never before dreamed possible.

A progenitor of Muzak, Cahill’s telharmonium was installed in New York City and connected to the city’s young phone system; music played on the instrument was then piped by way of telephone lines to a community of paid music subscribers (among the most enthusiastic of these early adopters was Mark Twain, a big supporter of such innovations). Soon after its inception, customers complained of music bleeding through into private phone lines, and Cahill’s experiment in electronically produced and delivered music only lasted a couple of years. But the principles of using pure waveforms to synthesize instrumental sounds and rhythms he pioneered laid the groundwork for the much more compact electronic organs developed in the 1930s. Brought into mass production by Laurens Hammond, these smaller electronic “tonewheel” organs were versatile instruments with big aural impact, affordable enough to find homes in churches and private homes across the world thereafter.

Barringer says that by the 1940s, “there were these amazing electronic music labs, all over the world. And in all of these centers, famous cliques of composers would get together and make revolutionary pieces – making music from tape or by using huge, room-sized computers and sound oscillators. They’d make these tape piece works, using sounds which hadn’t ever been considered as source material before – the most famous of these is probably the original ‘Doctor Who’ theme.” That theme song was made with actual analog tape loops in 1962 by a BBC Radiophonic Workshop studio manager, Delia Derbyshire. Working from a score by Ron Grainer, Derbyshire sliced, diced and remixed the tape to create both rhythm and sound by distorting and reproducing white noise and a recording of the sound of a single plucked string, using the manipulations of the simple waveforms created by test-tone oscillators –machines which, at the time, weren’t used to make music but to test studio equipment and recording conditions.

It wasn’t long before synthesizers became ubiquitous to musical experiences everywhere, Barringer says. Simply put, these pioneers of electronic music “discovered entirely new music forms.”

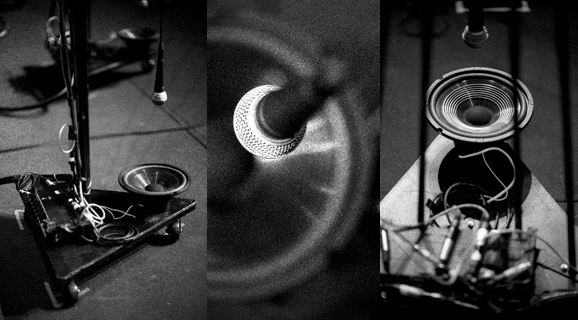

Photos by Zoran Orlic from Kronos’s production, “Visual Music”, which opens with Reich’s “Pendulum Music” for microphones, amplifiers, speakers, and performers. Courtesy of WQXR Radio’s website

For this weekend’s performances, Zeitgeist will highlight a few seminal works. Among them are two works by Alvin Lucier: “I am Sitting in a Room” and “Music on a Long Thin Wire,” which sets a wire into vibration by two magnets. Given the shifting variables that inherent in playing such a piece – the placement of equipment and the size and acoustic characteristics of the room, for example – “each performance will be an entirely unique experience, specific to this space,” Barringer says.

Zeitgeist will also showcase an example of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s work in “moment form”. “We’re doing this piece, ‘Microphanie I’ – one of the biggies. The performers manipulate a tam-tam and a pair of microphones; the piece makes audible all sorts of things in the sound spectrum that you wouldn’t have been aware of before – [by using these devices as instruments], the piece makes those sounds manifest.”

In addition to works by John Cage, Charles Dodge and Michael Oldfield, listeners will be able to hear a performance of Steve Reich’s “Pendulum Swing.” Barringer says, “We’re very interested in his work to do with phasing, the use of feedback.” There are speakers, with microphones suspended above them by cables of varying lengths; performers pull the cables and swing the microphones. Feedback is produced as the microphones arc toward, over and away from the speakers below. “With this piece, we’re learning something about the behavior of soundwaves in a space,” Barringer says. “You work out what you want the feedback to sound like ahead of time, and plot out position and movement of all the elements involved accordingly.”

That’s not to say chance isn’t involved, she says. “But the random parts of a piece like this are human, not mechanical in origin – say, if someone drops a pencil, or jostles the equipment. But the process, the principles behind performances of Reich’s pieces are quite deliberate.” She says, “It’s like science experiments by artists.”

Zeitgeist’s Early Music Festival, “The Electronic Age: Medium and Message,” will offer performances April 5 and 6 at 7:30 p.m., and April 7 at 2 p.m. in Studio Z, 275 East Fourth St., suite 200, St. Paul. Tickets are $10 for each performance; festival passes are available for $25. Find more information online: www.zeitgeistnewmusic.org.

Recent Content

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·

-

Artsarticle ·