Business Models

It’s one thing to design technology for usability. It’s another to design for sustainability.

Often the two challenges don’t overlap neatly, particularly when organizations are looking to derive revenue from sources other than users.

Both Facebook and Twitter are facing this very problem. They have enticed hundreds of millions of users to adopt their simple free tool to communicate and connect. They assume that most users are unwilling to pay for this service. So who, then, should foot the bill?

Advertisers are one answer, but not a complete or satisfactory one. Ads work only at large scale and are likely to turn off users if they overwhelm platforms.

If Facebook and Twitter struggle with this basic question, imagine the headache associated with building local engagement tools, which are often meant to be smaller and community focused.

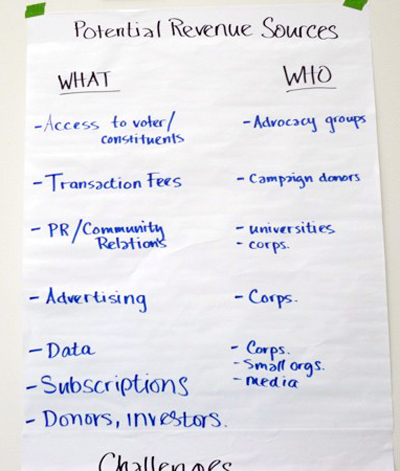

Summit participants explored sustainability challenges in two sessions and identified key challenges in building viable business models.

1) Users are often different from payers.

The bulk of citizens are unlikely to pay for tools that allow them to report potholes, brainstorm solutions, talk to neighbors, attend a virtual town hall, etc. Revenue will have to come from alternate sources, which implies competing interests. Technology for Engagement products must balance the needs of payers and users. One offsetting principle that makes this easier is that these tools often lower transaction costs for payers.

2) Scaling is difficult, but technology is often only cost effective at scale. Engagement tends to be place-based, but new technology investments often make sense only at a larger scale. Community Planit and Participatory Chinatown, referenced above, began as a series of face-to-face meetings with virtual reality simulations in one Boston neighborhood. It cost over $100,000 and involved hundreds of people. It is difficult to justify this type of expense unless these platforms get to scale. Alternative notions of scale and lower prototyping costs are both needed.

3) Reliance on philanthropy. The pool of money for engagement technology is small. Civic startups generally rely on philanthropic funding rather than venture capital. But the pressure for social entrepreneurs to adopt the nonprofit model may not be ideal, particularly since philanthropic capital to bring technologies to scale in the absence of revenue is scarce, unlike in the venture capital world where Instagram, Twitter, etc., could raise funding to scale without much revenue.

4) Government can be a tough customer. Local governments have a vested interest in more engaged communities, particularly to the extent that engagement technologies can make government faster, better and cheaper. However, governments have little appetite for the risk of adopting new technologies.

How have innovators responded to these challenges?

Many organizations have adopted a business-to-business-to-consumer model whereby earned income is generated from selling enterprise access to a community of users of a particular platform rather than from the users themselves. While it can be more difficult to scale this model (since revenue is not always in line with growth) it does provide earned income early on and therefore mitigates the lack of philanthropic capital available. Popvox, for example, is a nonpartisan platform that shares individuals’ opinions on legislation with Congress and generates revenue by selling “pro” versions of its advocacy tools to grassroots organizations.

All of the most successful organizations continue to experiment with both products and revenue sources on the path to growth. A few have been able to generate revenue directly from users.

• Change.org offers free tools to start online petitions, which add to their massive database of users. They then charge nonprofits to run campaigns to generate new leads from their database.

• Public Stuff and See Click Fix offer residents of a community a simple and free way to report and track a complaint. But clients include governments that pay for proprietary software to manage all the service requests.

• Front Porch Forum, a for-profit neighborhood information network in Vermont, generates advertising revenue from local businesses but also charges municipalities and interest groups for access to multiple neighborhoods within the platform.

Each of these products caters to multiple constituents and strives to solve the problems of both users and payers. While Change.org has developed tools that can scale easily, depending on whether an issue is local, national or global, PublicStuff chooses to serve individual communities but offers a product that can spread to many others.

Both Change.org and PublicStuff are companies that have managed to leverage venture capital.

Raising money from “the crowd,” a funding approach popularized by Kickstarter, has proven successful for many creative projects. Its payout this year is expected to top $150 million. However, whether technology for engagement is a good fit for crowd funding is still unclear.

What’s clear is that the crowd is rising. So may a new funding landscape.

Recent passage of the JOBS Act may jumpstart investments, rather than merely attracting donations through crowd-funding portals. The Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act, introduced by House Republicans and signed into law by President Obama, allows startups to seek funding from small “unaccredited” investors. This could unleash not just more funding but a greater range of innovation aimed at the masses. Their values may be very different from that of traditional venture capitalists.

Recommendations:

- Diversify revenue sources.

- Solve the problems of both users and payers.

- If scale is unlikely, focus on spreadability.

- Help communities decide what kind of civic infrastructure (and technologies for engagement) they want.

- Explore crowd funding as an option.