Cities face an uncertain future in the wake of Covid-19. Some predict a new wave of urban flight as public health, employment and affordability challenges intersect with an upsurge in remote work and connectivity that allows for more mobility. A recent Harris poll revealed that 39% of city-dwellers are currently considering moving to a less dense community. Others say the crisis will spur a reimagination of social infrastructure and urban life together as innovative leaders start to look ahead, become more nimble and revisit city plans to build back better, more resilient communities.

As the pandemic causes us to evaluate where and how we live, understanding what connects people to place is more important than ever. But what exactly generates a real attachment to the community over the long term? What provides the stickiness or emotional and practical commitment to stay rooted in a community over time?

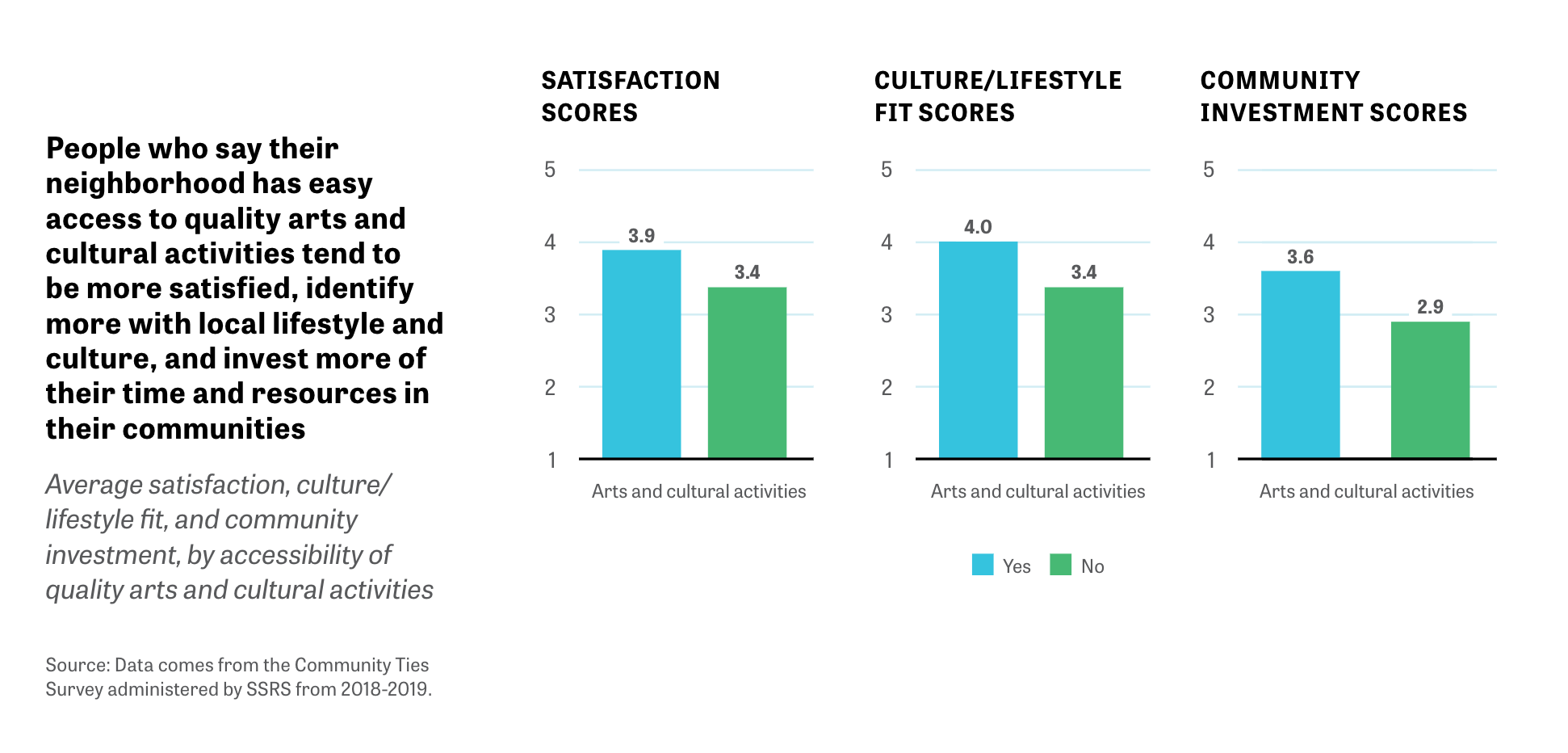

A landmark Knight Foundation report produced by Urban Institute surveyed over 11,000 Americans to explore this very topic, developing a rich and authoritative dataset on what drives community attachment across a diverse set of metro areas and demographic groups. The study reveals that the features of city life that most fuel attachment are essentially social in nature – such as cultural and recreational spaces – but enjoying a sense of public safety is a driver as well. Key findings shed light on why people stay in a city, and what cities can do to strengthen ties between residents and their local communities. Of the dozen urban amenities explored, arts and cultural activities stood out for its potential to boost various indicators of attachment, from higher feelings of satisfaction and personal fit with the city, to behaviors such as greater investment of time and resources in the community.

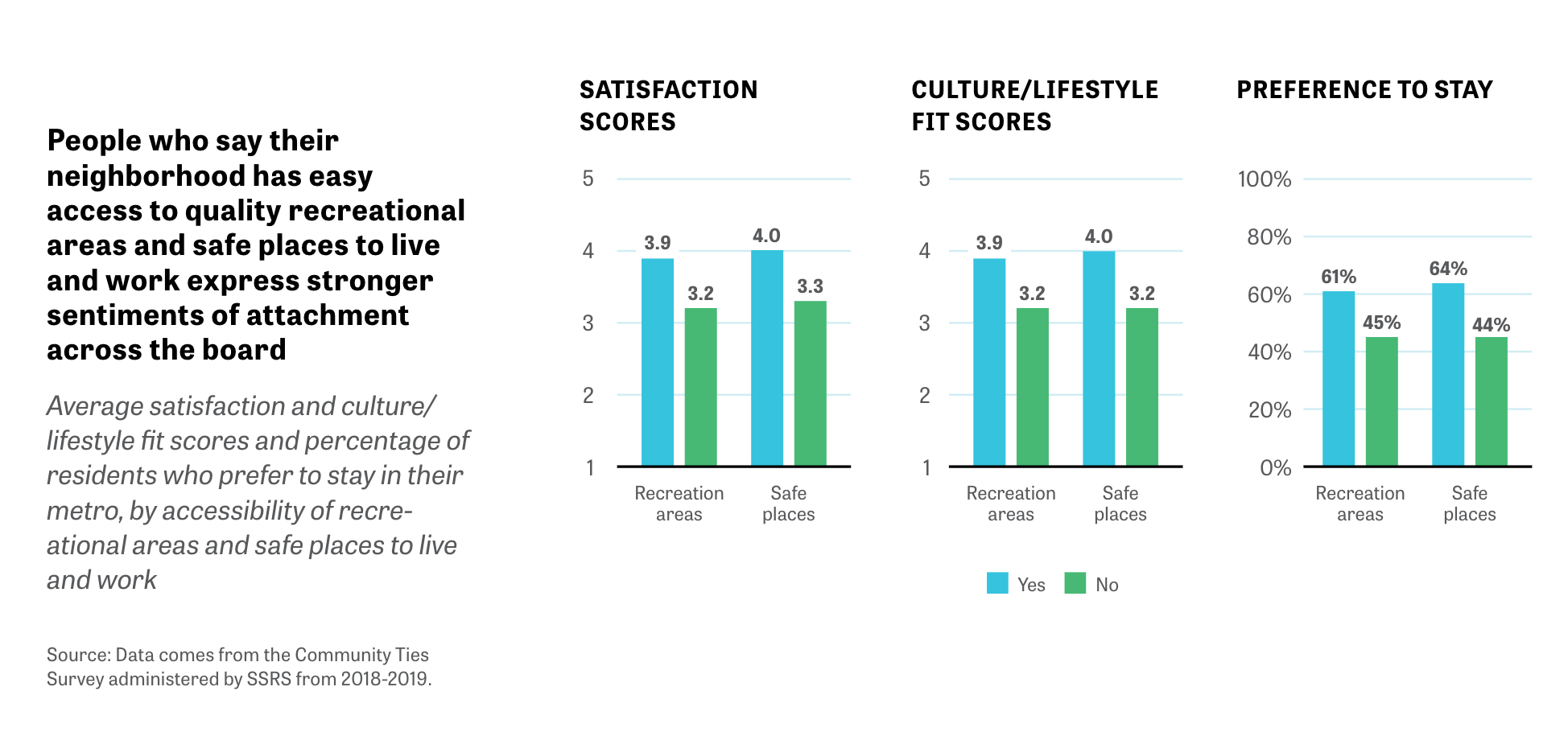

People with easy access to recreational areas (parks and other outdoor amenities) and safe places to work and play also reported stronger feelings of attachment and showed a preference for staying put. Attachment was also deeper for people who spent more time in the main city, as well as those who reported choosing the city for “quality of life” reasons versus those there for family or jobs.

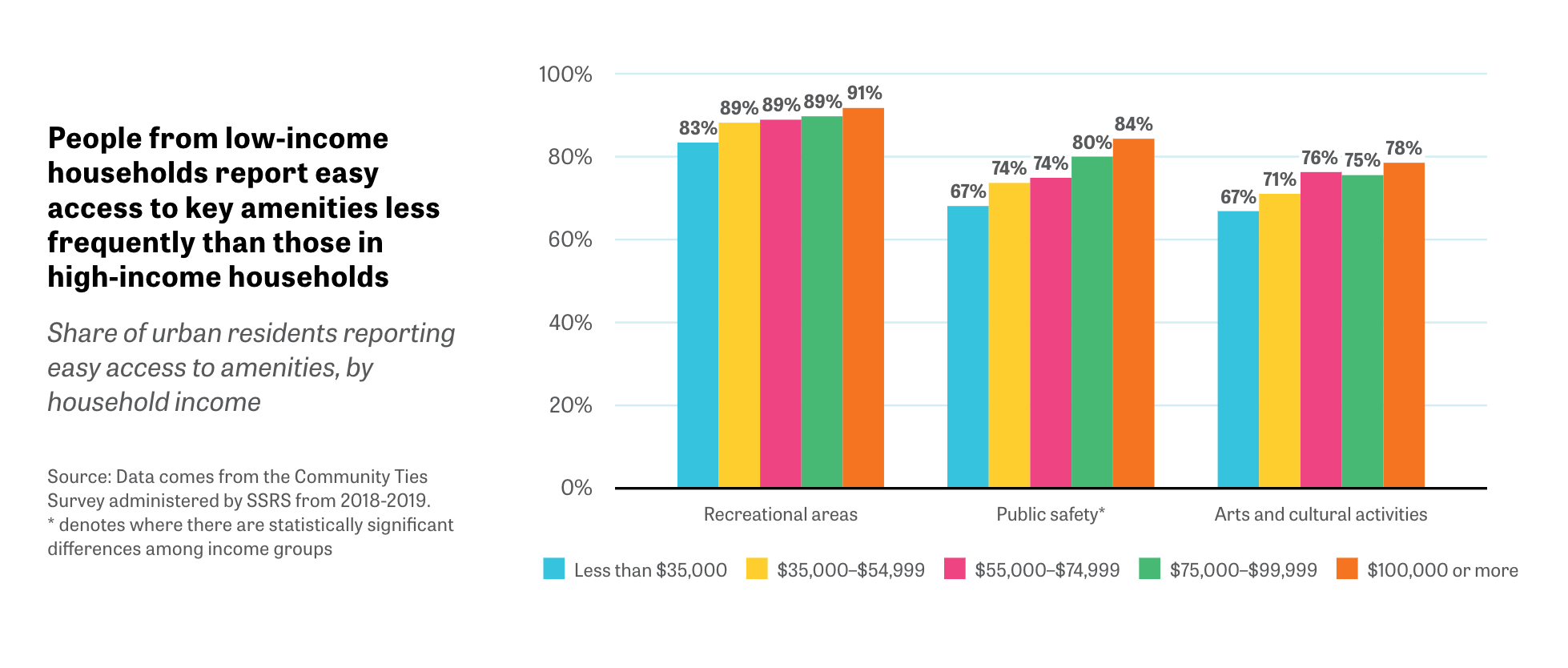

However, the data also shows that while quality of life amenities matter more to residents of color and lower income groups, they report having more trouble accessing them. Investments in quality of life city amenities should consider any existing inequities and design approaches that address — and not exacerbate them.

Perhaps ironically, some of the things that foster deeper attachment to our cities are also among those most affected by the shutdown: access to museums, concerts, playgrounds, beaches, and to a general sense of safety, while out and about in our community. As social scientist and Knight Public Spaces Fellow Eric Klinenberg argues, investment in social infrastructure (including libraries and parks) is critical in revitalizing civic life and ultimately a resilient community during a crisis. The current pandemic is an opportunity for cities to lead with engagement and inclusivity as they consider redesigned versions of these amenities at the heart of city life.

Thoughtful communities will strive to rebuild in a way that is resident-driven, with community members at the table, particularly where quality of life amenities are scarce. In the Knight community of Philadelphia, listening to resident needs during the pandemic resulted in a simple solution: roping off “playstreets” in neighborhoods that lack outdoor recreational space to create it, while empowering neighbors to manage the program. This is just one of many creative solutions popping up as communities and residents work together to reimagine the shape of urban life. The time is now for American cities to focus on these questions if they are to successfully reopen and reinvent themselves as desirable cities of the future. Instead of reorienting our cities towards sprawling suburbs, this study suggests that providing equitable access to key quality of life amenities at the heart of communal life — while solving for safety — might be the new holy grail for post-pandemic community design.

Click here to view and download the full report.

Evette Alexander is a director of learning and impact at Knight Foundation and Lilly Weinberg is the program director for community foundations at Knight Foundation.

Community Ties: Understanding what attaches people to the place where they live

Understanding what attaches people to the place where they live